In 1972, a group of feminists– Silvia Federici, Selma James, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, and Brigitte Galtier– started the International Wages for Housework Campaign (IWFHC) that demanded that women be compensated for their invisible labour.

The movement spread throughout the Western world through the 1970s and continues to hold momentum to this day. By demanding wages in exchange for housework, it introduced to the world the radical perspective that domestic labour silently, unquestioningly performed by women holds concrete value.

In 2021, amid the pandemic, Federici– who has continually advocated for the cause and focused her work in the same direction– reentered popular discourse through a New York Times article titled ‘The Lockdown Showed How the Economy Exploits Women. She Already Knew.’ The domestic confinement caused by the pandemic and our unavoidable confrontation with the reality of domestic work have forced us to acknowledge the reproductive labour upon which our homes are built.

The acknowledgement of reproductive labour

The Marxian concept of reproductive labour can be defined as “the work required to sustain human life” which involves caregiving, cooking, cleaning, and any other adjacent domestic labour. It pools into the larger social phenomenon of social reproduction, first conceptualised by economist Francois Quesnay, which configures the generational sustenance of the members of our society.

Within capitalist society, reproductive labour becomes another form of labour that the structure exploits. And since waged labour holds a definitive value and all roles (from CEO to janitor) are monetarily compensated, they are also hierarchically aligned. When looked at from the purview, reproductive labour falls at the complete bottom.

All societal roles are divided and compensated according to their value-production & contribution to society. The value-production of household work is taken for granted because of how invisible, unacknowledged, and built-in it is.

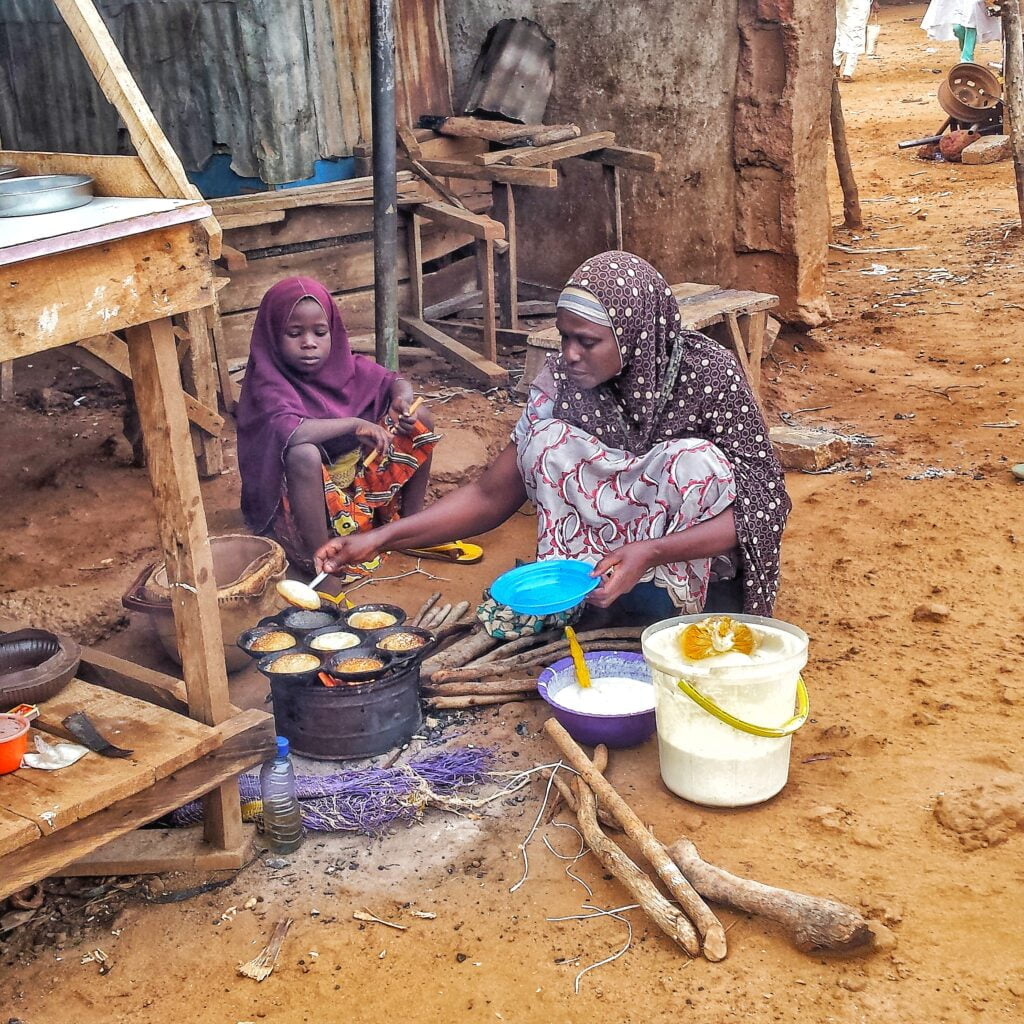

For centuries, women (especially proletariat women) have assumed the obvious role of performing reproductive labour while the men of the family do the ‘real,’ work out in the world. The essentiality of this work has allowed it to go unacknowledged because the house will be cleaned regardless, children will be taken care of regardless, and, depending on financial circumstances, food will be made.

The concept of reproductive labour was primitively introduced with the Marxist school of thought by Friedrich Engels in ‘The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State,’ where he emphasises the work that acts as a backbone to society through the “production and reproduction of immediate life.”

The solution he proposed for women’s liberation was women’s public productive participation and abolition of the monogamous family unit. Federici extends on this, and more importantly provides a woman’s perspective on it, by proposing that in the first place, we need to recognise that domestic labour is labour and that it is not a free activity.

Exploitation through Reproductive Labour

The capitalist system is undeniably exploitative. As Karl Marx explains in Volume One of Capital, all objects that satisfy our wants and needs are commodities and all acts that contribute to making these commodities amount to commodity production. Labour power is bought by capitalists to facilitate this, which is done with money. Thus labour too becomes a commodity that is bought and sold.

Commodities are made and sold to procure and advance capital, which is reinvested into commodity production. The functioning of capitalism can thus be seen as a cycle of economic transactions. In the examination of the capitalist system, what often goes unnoticed is the work holding up productive labour. To run any household, a myriad of tasks need to be performed from the dawn of the day till bedtime. Unlike productive labour, which has fixed hours, domestic work is a full-time job in the true sense of the word.

IWFHC co-founders Dalla Costa and James in their book ‘The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community,’ rightly say “Where women are concerned, their labour appears to be a personal service outside of capital.” Reproductive labour is performed without choice, compulsorily, because it has to be performed. The functioning of the rest of society lies in the work performed by homemakers, housekeepers, and women– work done for the sake of sustenance, if not nurture.

As the importance of jobs, with industrialisation, liberalisation, and globalisation, became higher & more intense, the intensity of domestic labour too increased. Opportunities for rest and leisure are sparse if not non-existent, depending on social and economic conditions. Furthermore, in our global economy, there exist internal hierarchies within social reproduction that hinge on class, race, caste, etc as reproductive labour is often also displaced onto people ranking lower in the hierarchy.

With this much nuance that deserves more dialogue, it is surprisingly not addressed in detail in classic Marxist thinking. Federici argues that it is so because his approach was purely technologistic and without focus on affect.

The affect of exploitation

The concept of affect was first theorised by psychologist Silvan Tomkins, describing affect as the biological, emotional response to something. The idea of ‘affect‘ was developed by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt in the conceptualisation of Affective Labour. In ‘Affective Labor and Feminist Politics,’ Johanna Oksala describes affective labour as “the labour of human contact and interaction, which involves the production and manipulation of its affects,”; reproductive labour can be seen as a subset of affective labour that focuses specifically on the performance of household duties.

What isolates reproductive labour from being recognised and valued is its intangibility. Ironically, its intangible nature is what makes it so essential. By proposing to wage it, Marxist feminists aim to attribute value and arguably flip the immeasurability of reproductive labour. Value (or its lack) attached to reproductive work subsequently also reflects the value of women’s social position.

Beyond suffrage, equal rights, and better pay, this remains a trap in which women exist and perhaps also one that will take longer to escape. Thus, the value of Woman Labour, as Federici calls it, cannot be left out of Marxist discourse.

Practical application of wages for housework

In 2019, research carried out by Oxfam reported that the global value of unpaid care work would account for $11 trillion. Several attempts have been made to address the issue of women’s unpaid labour. IWFHC organised the Global Women’s Strike (GWS) in 2000, demanding tangible pay in exchange for care work. James continues to spearhead GWS and advocates for the policy introduction of a ‘care income.’

The actual structural introduction of such an income/stipend has been debated and considered, although not yet implemented. The cost of reproductive labour has been speculated and calculated by many, roughly estimating ₹45,000. In India, the former Women and Child Development minister, Krishna Tirath, proposed a “salary for housewives,” mandated to be paid by the husband in 2012 which was never officially carried out.

Regardless, even the proposal of the idea that housework should receive compensation in itself is radical since it has created, and continues to create, a discussion about the exploitation of women’s unpaid, unappreciated labour. IWFHC is only the first step, the first proposed solution, to valuing domestic labour; once we cross the barrier of addressing this gendered exploitation, there will only be more we can do to fix it.

About the author(s)

Spoorthi is a material feminist, academically rooted in cultural studies. She enjoys analyzing films and applying feminist critique to media & media structures.