The revolt of 1857 is often called the “First War of Independence,” and it saw widespread participation from people of all castes and religions. Different interpretations of the Revolt have drawn our attention towards different motives and expectations of the native people that they wished to achieve through their mass participation.

For some, the major reason for participating in revolt was mainly to fight against the British East India Company for destroying their way of life prevalent in the region before the conquest of the British. For others, it was a means to secure the traditional privileges and livelihood that they enjoyed under their rulers. More importantly, many people including small tenants and cultivators saw it as an opportunity to overthrow the oppressive regime and their support of rich nobles and landlords.

Apart from the elite women belonging to the hereditary class with a ruling background, several ordinary middle-class women also participated in the revolt. Thus, one must also understand those women who participated in the revolt as victims of society rather than as active participants.

The fact that an acceptance of the cruel and oppressive regime of British rule and an inherent contradiction that existed in the society inspired people from almost all sections of society to participate in the revolt including the women who participated equally with the men. The same has eluded the pages of many history textbooks neglecting the contributions that these women made to the revolt of 1857, who were guided by their consciousness with no immediate personal or recognisable political reason and in their making the Revolt a great success.

Locating women in the People’s War of Independence

The Revolt of 1857 not only provided us with an account of ‘sepoy mutiny,’ but also a narrative concerning the active participation of women from the marginalised sections. Many of the colonialist and nationalist writings have subdued their voices and have considered them insignificant for scholarly considerations. The fact revolt presented a major challenge to the supremacy of the British, encompassed a large part of the Indian subcontinent and saw widespread participation from the elite as well as the marginalised communities including women who had very few rights and opportunities in a traditionally male-dominated society of the late nineteenth century.

Many of these women and their contribution to the Revolt have been forgotten and much information about their life and their struggles have also not been recorded by the mainstream historiographies. Not surprisingly, these women were bracketed under the label of “lesser known” women who mainly assisted their queen in fighting with the British. Some of them were assigned roles such as secret messengers, some worked as prostitutes, while others were depicted as ordinary participants of the revolt.

Azizun Bai

Lata Singh in her work Visibilising the ‘Other‘ in History Courtesans and the Revolt brings into light the image of a courtesan who is denied the credit and appreciation for her contribution to the revolt by the nationalist discourse.

Azizun Bai and her participation in the revolt have always been disregarded because she has been recognised neither as a respectable wife nor as a respectable mother. Belonging to the singing and dancing community, she has been represented in ways that do not confirm the growing nationalist and colonialist discourses.

Some of the dominant nationalist bourgeoisie perceptions of these courtesans are derived from the fact that their construction of an image of a respectable woman as an epitome of ‘mother India,’ proved to be contradictory with the notion of women entertainers who were actively engaged in the public sphere to earn money.

From the colonialist perspective, the artistic and creative elements associated with these women were neglected and impositions of various kinds were introduced to regulate them including Britain’s Contagious Disease Act of 1864 to prevent the spread of venereal diseases among European soldiers. Under British rule, a loss of cultural power was felt by many women like Azizun Bai who lost the protection and patronage of the court rulers, in addition, the initial loss of Nawabi culture with subsequent imposition of penalties and confiscation of their properties because they participated in the revolt of 1857 and the siege of Lucknow meant not only the loss of livelihood for them but also neglect of the wider freedom that they had earlier under the patron of the nawab.

Jhalkari Bai

Understanding the life of Jhalkari Bai and her contribution to the revolt reiterates the fact that what is called a “sepoy mutiny” by British historians and the “first war of independence” by nationalist historians reflected a variety of congruent and conflicting motives to participate in the great rebellion of 1857.

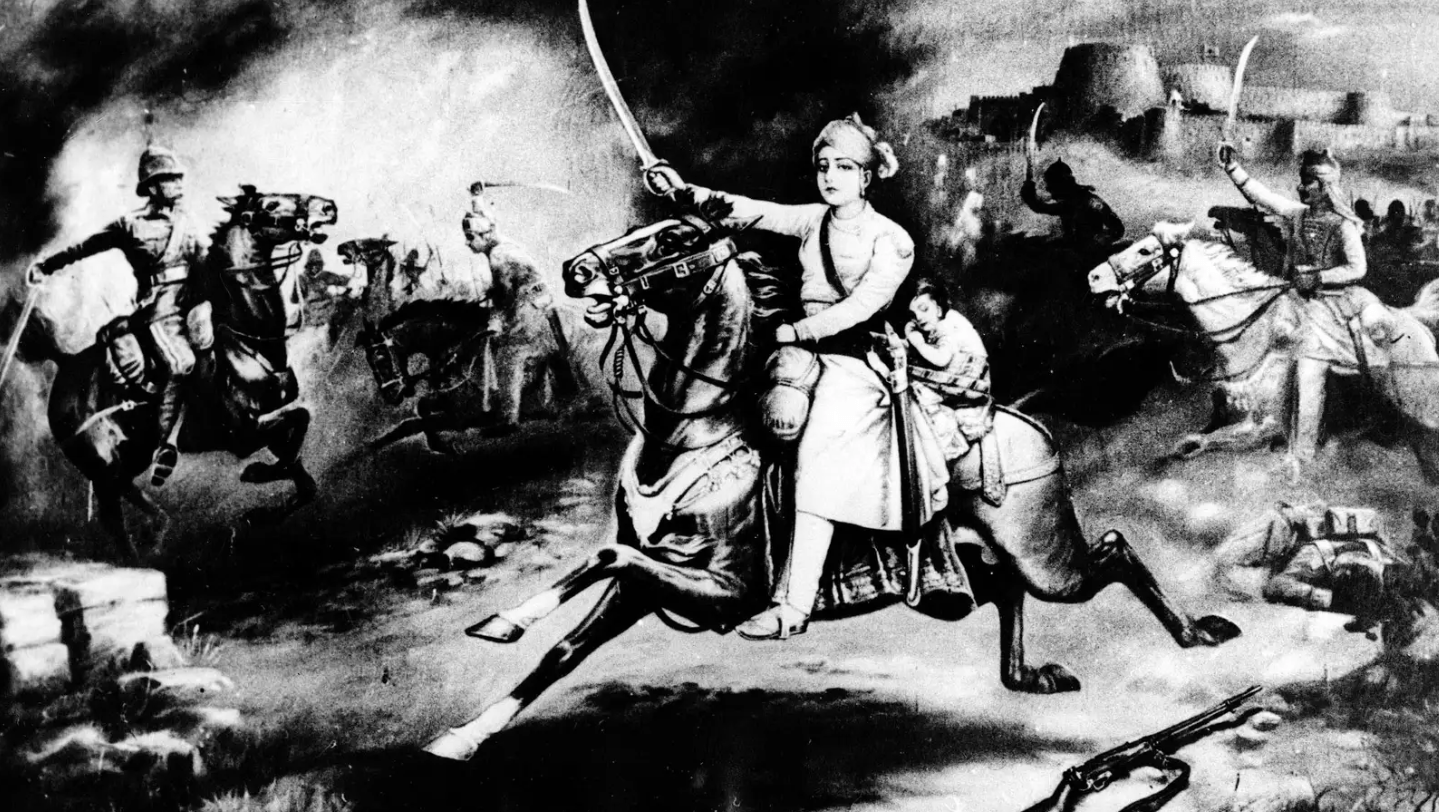

Jhalkari Bai, a legendary Dalit woman warrior played an important role in the revolt of 1857 during the battle at Jhansi. She was one of the trusted advisors of Rani Laxmibai and also served as a soldier in the army of the queen. Leading the girl’s wing of the queen’s army (Durga Dal), Jhalkari Bai helped the queen of Jhansi to escape from the palace and she appeared in the guise of the queen to lead the movement. Her face and physique were similar to Rani Laxmibai’s; this helped the queen to fool the Britishers.

From the life of Jhalkari Bai, one story that marks the contestation between the dominant colonial and Hindu Brahmin narrative on the one side and the Dalit history on the other side is that she is blamed for killing a cow which was kept hidden by a Brahmin.

The debate over killing a holy cow has also supported a more authoritative and mature Dalit history where the queen of Jhansi is seen as reluctant to fight the British and it was Jhalkari Bai who fought till the end and proved to be a real warrior. It is often said that it’s her sacrifices and love for the country that needs to be recognised as she had nothing to gain and lose from the war, after losing her husband in the battle, she was neither a queen nor a daughter of a jagirdar or a wife of a rich feudal lord fought selflessly without surrendering to the Britishers, writes Charu Gupta, 2007.

Uda Devi

Another legendary woman from the revolt of 1857 was Uda Devi belonging to the Pasi caste which was considered as an untouchable caste, Uda Devi has been represented as playing a limited role in assisting Begum Hazrat Mahal during the siege of Lucknow. It was the Britishers who recognised her attacking them from the tree top; she used tactics of concealed war and was trained in skills like archery, shooting, and horse riding. In addition, numerous stories and local portrayals of Uda Devi have shown her single-handedly killing a tiger. Most of the representations of these Dalit viranganas have been portrayed as brave, superwomen, providing a counter perspective on Dalit history and the Revolt of 1857, writes Charu Gupta.

In contrast, in the colonialist representation of these women, they have often been labelled as “Amazons of India” and ultimately were defeated and met a tragic end in their encounter with the Britishers. For instance,

Gordon-Alexander’s account of the storming of Sikandar Bagh by British troops states: “In addition… there were… even a few amazon negresses, amongst the slain. These amazons having no religious prejudices against the use of greased cartridges, whether of pigs or other animal fat, although doubtless professed Muhammadans, were armed with rifles, while the Hindu and Muhammadan East Indian rebels were all armed with musket; they fought like wild cats, and it was not till after they were killed that their sex was even suspected.”

Moreover, adding a twist to their representation of these warrior women, It is said that after realising the brave feet of Uda Devi, even British officials like Campbell were forced to bow their heads to her dead body as a mark of respect.

Understanding feminist historiographies from the subaltern

Charu Gupta’s “Dalit Virangana and the re-invention of 1857” explores the representation of the revolt of 1857 in contemporary popular Dalit literature. Dalit thinkers and writers have emphasised the fact that one important reason for the rulers and the elite to participate in the revolt was their motive to restore their lost privileges, and power, and to preserve their hereditary customs.

For Rani Laxmibai securing the throne and the impact of forcefully imposed laws like the doctrine of lapse restricted her from the exercise of power, similarly, Begum Hazrat Mahal wished to enthrone her son Birjis Qadr as nawab of Awadh. This is also a clear exposition of the fact that history has always been an important site of contestation.

Understanding dissent and resistance from everyday political action requires us to engage with what has been termed as the ‘other subject,’ who constitute people ranging from tribals, peasants, cultivators, innkeepers, and the other subordinate classes whose names have been forgotten with time.

For instance, the subaltern histories have attempted to seek and explore alternative heroes from the revolt of 1857 whose national consciousness drove them to the battle. Ranjit Guha’s “On some aspects of the historiography of colonial India” has focussed on the principal actors of the major events of colonial India. Guha’s work has also earned accolades for indigenous leaders independent of the elite who were honoured by the masses.

On finding the biases and value judgements of the nationalist and colonialist historical works, Guha considers it as a ‘binary relationship,’ between the subaltern and the ruling class which remains shunned on the margins and undocumented. These few intellectual reflections on the revolt point out an alternative cultural–ideological evolution of women’s history.

REFERENCES

1. Pati, Biswamoy. “Historians and Historiographies: Situating 1857”, 2007, EPW, pp. 1686 – 1691.

2. Singh, Lata. “ Visibilising the ‘Other’ in History: Courtesans and the Revolt”, 2007, EPW, pp. 1677- 1680.

3. Roy, Kaushik. “The Beginning of ‘People’s War’ in India”, 2007, EPW, pp. 1720- 1728.

4. Gupta, Charu. “Dalit ‘Viranganas’ and Reinvention of 1857”, 2007, EPW, pp. 1739- 1745.

5. Guha, Ranjit.(Ed.), subaltern studies, Oxford university, 1982, pp. 1-8.

Amazing article 👏..Glad that the writer has put in so much effort to cover all aspects which is generally lacking in others.

👍 keep up the great work

Thank you Divya.😊

Drawing from subaltern studies, excellent survey of subaltern women’s participation in the 1857 revolution.Generally neglected in mainstream studies that mostly focused on the participation of elite women.

Thank you Harshit!

A very fresh take on the women participation in the freedom struggle through the subaltern lens. A must read for everyone out who want to capture a holistic picture of the freedom movement.

Thank you Mannsi. 😊

thank you Harshit

Excellent survey of subaltern women’s participation in 1857 revolution.👍

Amazing article and the writing process.. keep up the good work Drishti. Hope to read many more.

Thank you Anuradha 🙂