As the 2024 Lok Sabha elections unfold in India, the spotlight once again turns to the electoral landscape and the mechanisms available for voter expression. Among these mechanisms is the ‘None Of The Above’ (NOTA) option, introduced to allow voters to express their dissatisfaction with the available candidates

But, what is NOTA?

The NOTA, short for ‘None Of The Above,’ provides voters with the opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with all candidates contesting in their constituency during an election. This option allows individuals to officially cast a vote of rejection towards all contenders, signaling a stance of disapproval or lack of confidence in the available choices.

The NOTA, short for ‘None Of The Above,’ provides voters with the opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with all candidates contesting in their constituency during an election.

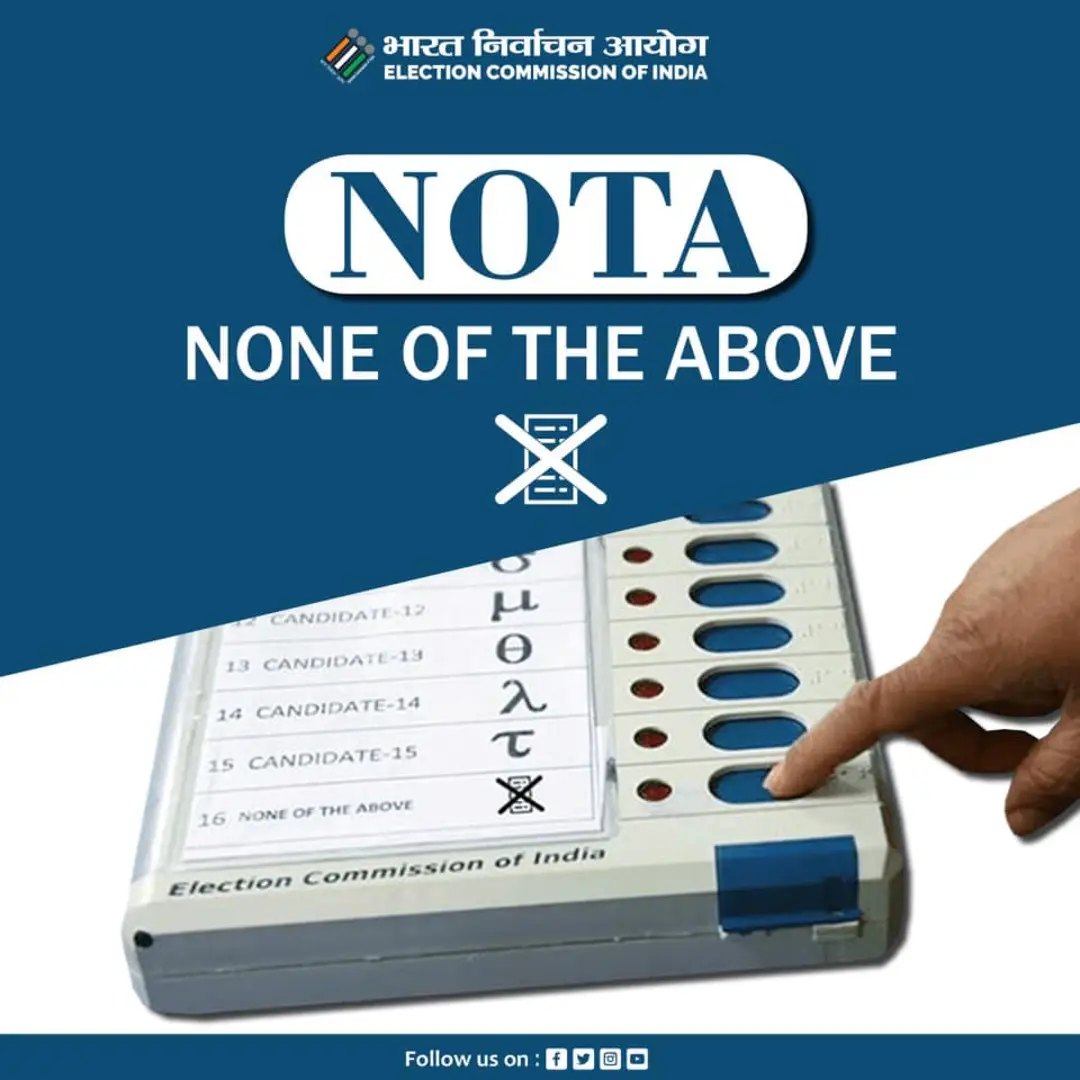

The inclusion of the NOTA option dates back to 2013 when it was integrated into Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) during assembly elections across five states: Chhattisgarh, Mizoram, Rajasthan, Delhi, and Madhya Pradesh. This development followed a significant legal precedent set by the Supreme Court in the PUCL versus Union of India case, which emphasised the importance of providing voters with a means to register their disapproval if none of the candidates aligned with their preferences or ideologies.

Under the case, the Election Commission emphasised the necessity of introducing a ‘None of the Above’ or ‘NOTA’ option on EVMs/ballot papers to promote democracy. They highlighted that this move, besides enhancing the fairness of elections in a democratic setup, would empower voters to express their dissent or disapproval towards contesting candidates. Additionally, the inclusion of NOTA was seen as a means to curb bogus voting, ultimately benefiting the electoral process by fostering transparency and accountability.

While it is essential for secrecy and democratic expression that the NOTA option is available on electronic voting machines, it doesn’t necessarily mean that NOTA votes should be included in the final count. A NOTA vote is essentially a neutral vote, devoid of any numerical value when determining the winning total. It’s crucial to differentiate between a neutral vote and a negative vote. The court’s perspective on NOTA was that it would encourage political parties to nominate better candidates. The idea was that as more voters express their disapproval through NOTA, parties would be compelled to field candidates with integrity, leading to a systemic change reflecting the will of the people.

Does the NOTA vote count?

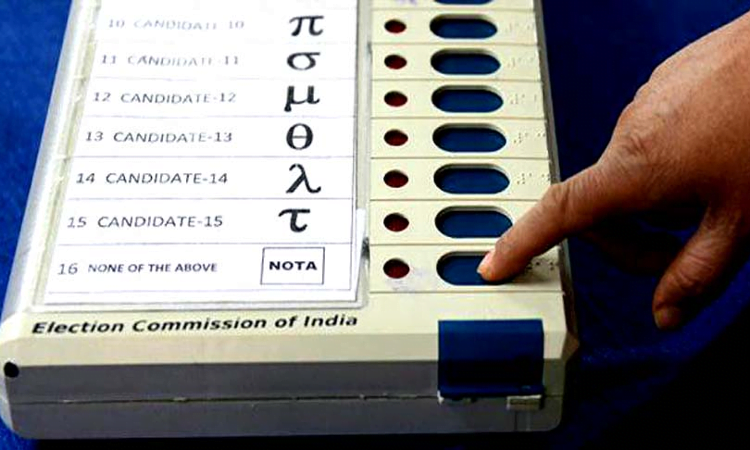

NOTA, or the ‘None Of The Above’ option in Indian elections, doesn’t hold any direct electoral value. Even if it receives the highest number of votes, the candidate with the most valid votes, even if just one, will still be declared the winner.

NOTA, or the ‘None Of The Above’ option in Indian elections, doesn’t hold any direct electoral value.

Since the decision to introduce NOTA, there have been extensive discussions regarding its potential electoral implications, making it a highly debated topic. On one hand, NOTA serves as a valuable tool to assess the level of dissatisfaction among voters. It indicates the number of voters who find none of the candidates suitable to govern them.

However, there’s another perspective that suggests NOTA plays a crucial role in the electoral outcome by cutting votes from political parties. This theory argues that NOTA contributes to shifts in victory margins by reducing the overall votes received by parties.

In essence, NOTA’s impact on elections remains a subject of ongoing debate, with some viewing it as a measure of voter discontent and others highlighting its potential influence on victory margins by diverting votes from political parties.

NOTA in minority opposition and fascist electoral systems

In contexts where opposition forces are already diluted, and electoral systems are perceived as undemocratic or even fascistic, the utility of the ‘None Of The Above’ (NOTA) option comes into question. Take, for instance, historical situations where authoritarian regimes or deeply entrenched political structures have stifled opposition voices and manipulated electoral processes. In such environments, NOTA may be viewed as a symbolic gesture rather than a catalyst for substantive change.

In contexts where opposition forces are already diluted, and electoral systems are perceived as undemocratic or even fascistic, the utility of the ‘None Of The Above’ (NOTA) option comes into question.

The perception of futility often arises among voters who believe that their dissatisfaction, expressed through NOTA votes, won’t lead to tangible differences due to systemic biases or limitations within the electoral framework. Additionally, casting a NOTA vote risks inadvertently legitimising the status quo, especially if the outcome remains unchanged despite a significant number of NOTA votes. This scenario can be seen as acceptance or validation of the existing power structure, reinforcing the entrenched regime or dominant political forces.

Moreover, when opposition options are limited or fragmented, voters may feel compelled to choose between available candidates rather than opt for NOTA. The fear of dire consequences from an unfavourable outcome may overshadow the symbolic act of casting a NOTA vote.

In such circumstances, the focus often shifts towards advocating for broader structural reforms rather than relying solely on NOTA as a means of expressing discontent. NOTA’s effectiveness is thus questioned in contexts where the opposition is already a minority and where electoral systems are perceived as inherently biased or unjust.

One historical example where the effectiveness of the NOTA option was questioned due to a perceived lack of impact and systemic limitations is the case of elections held under authoritarian regimes or during periods of political repression.

During the Soviet era in Russia, particularly under the leadership of Joseph Stalin, elections were often seen as highly controlled and manipulated processes designed to maintain the dominance of the Communist Party. Opposition voices were suppressed, and electoral outcomes were predetermined to favor the ruling regime.

In such a context, the introduction of a NOTA option would have been symbolic at best. Despite any significant number of voters expressing dissatisfaction through NOTA votes, the electoral results would likely have remained unchanged, with the Communist Party continuing its stronghold on power.

As voters exercise their right to choose, the role of NOTA raises questions about the broader dynamics of political participation, accountability, and the need for continuous reforms in India’s electoral framework. In conclusion, while NOTA serves as a mechanism for democratic expression, addressing its limitations and exploring avenues for meaningful electoral reforms remains imperative for fostering a more responsive and inclusive democratic process in the country.

About the author(s)

Anuj is an urban practitioner and an independent writer. He's mostly interested in Feminist Urbanism and the intersection of various identities in the urban. He is a graduate of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements and has disciplinary training in Urban and Regional planning.