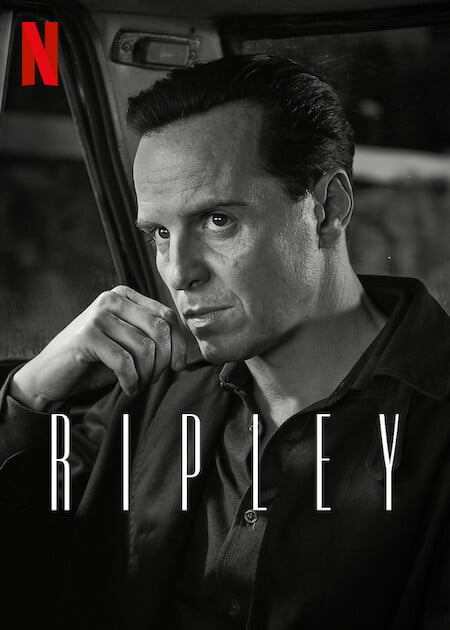

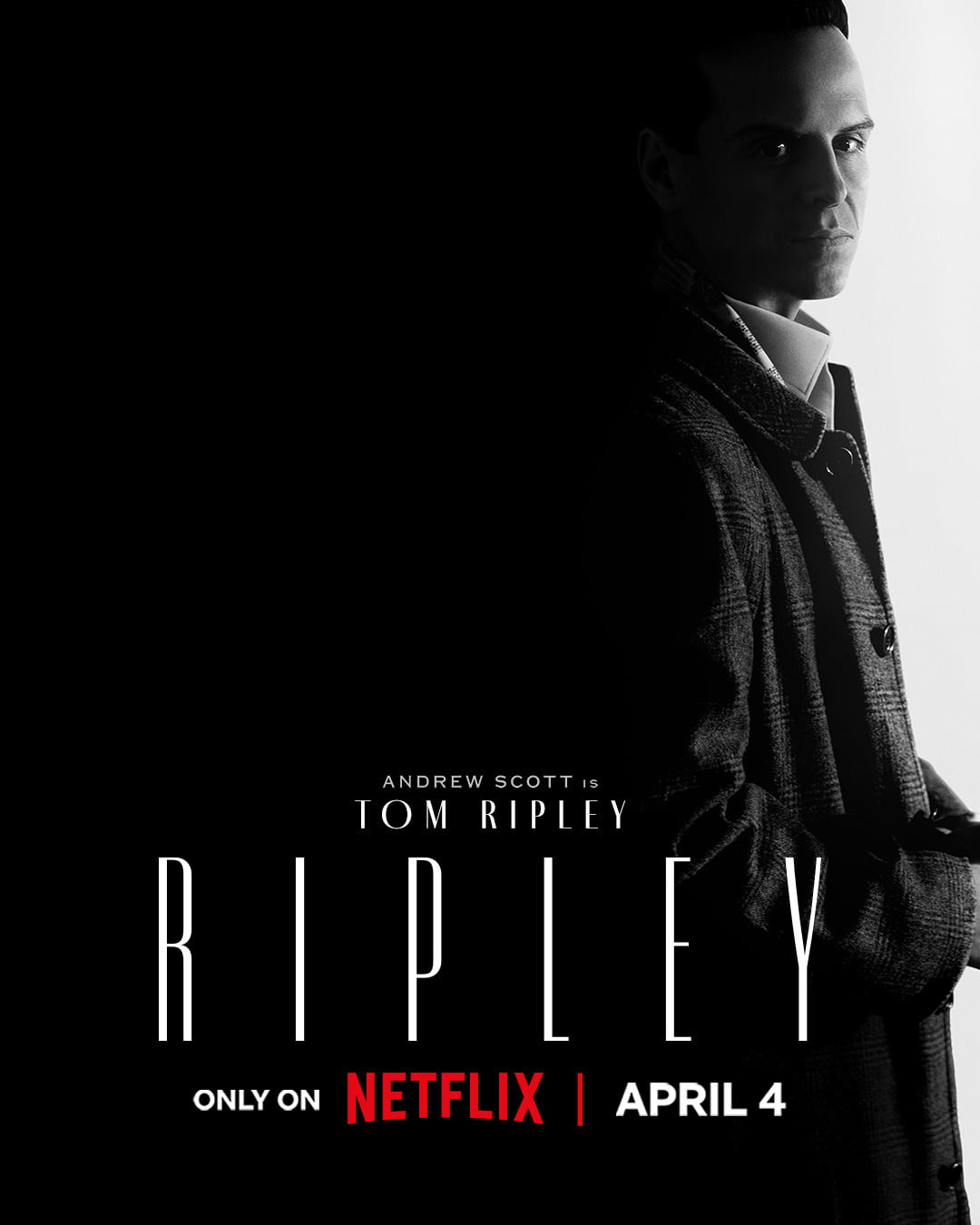

Andrew Scott has arrived. Through his masculine charm and expressive eyes, Scott burns through the screen and etches himself in our psyche. He is the infamous eponymous anti-hero of Ripley, the petty thief who commits white-collar crimes and lives in a borderline flophouse in New York, yet makes us root for him.

The black-and-white, almost noirish adaptation of Netflix is scintillating. Beautiful cities with sprawling roads and breathtaking views are beautifully translated in greyscale.

Patricia Highsmith’s titular antihero is adapted into the Netflix eight-part series letting us into every crevice of his existence. The black-and-white, almost noirish adaptation of Netflix is scintillating. Beautiful cities with sprawling roads and breathtaking views are beautifully translated in greyscale.

The Netflix series is the first time the famous pulpy novel (Ripliad) has been adapted in this format. In 1999, Anthony Minghella adapted it into a film, The Talented Mr. Ripley where Matt Damon played Tom, Jude Law played Dickie, and Gwyneth Paltrow played the character of Marge.

Ripley is visually stunning

In a world of graphics and colour manipulations, Ripley is shot in stunning black and white by the cinematographer Robert Elswit. (who won an Oscar for There Will Be Blood) The cities shot through long alley shots and water ripple reflections create a sense of nostalgia and intrigue.

American alleyways and giant doors are captured with a sense of boast and Italian stairways to Roman waters are caught with reverence. The entire series is calming and thrilling at the same time. The audience is transported to a world of less chaos communicated impeccably through carefully orchestrated shots.

Sin and punishment in Ripley

No one is innocent in Ripley. From the conman to the aristocrat, all are guilty and the guilt is relayed through the screen. The serious eyes and the biblical references almost spell the conundrum of sin and punishment for the audience.

The easy references through dialogues and plot twists reinforce the underlying tension of sin and punishment. They give the series an almost biblical existence.

The lack of guilt

The petty crimes of diverting the mail and letters go almost unnoticed and unrepented. Tom Ripley is an interesting thief, he does not apologise for his actions or wile away in guilt. He commits the crimes with a sense of nonchalance.

He does not care that he is taking away, he claims it as his own. He moves with a sense of belongingness, like he owns a piece of what is best in the city and it must rightfully belong to him.

Ripley does not abide by any biblical right and wrong, and there is no justice. Tom Ripley comes, takes, kills, cleans, and then is hosted by the aristocrats. He does not apologise and we never feel the need for his guilt.

The “have” and “have not”s

From a conman living in a dreary dungeon with creaking pipes and leaking walls to a a man residing in rented palace with a private canal, Ripley makes the jump we can’t. He lives the dream of every outsider who craves to move in the high circles of Europe and wear “burgundy paisley silk dressing gowns”.

From a conman living in a dreary dungeon with creaking pipes and leaking walls to a a man residing in rented palace with a private canal, Ripley makes the jump we can’t.

We don’t know much about Ripley, his home or his family. He is just one of us, a man who does not have and longs for all things nice. We see glimpses of his mother (maybe) screaming from the dentist’s chair. Is he an orphan looking for a family? Or just a conman looking for opportunities to move up the social ladder?

How do you climb up in the world of money? How do you snatch a place on the balcony overlooking the ocean? Tom Ripley cons to build his palace and we are with him throughout the journey.

Tom Ripley and identity theft

Ripley is shown forging cheques and pretending to be a finance company. He wins some and loses most but keeps at it. Stealing identity and camouflaging is his greatest gift, and he uses it to the best of his ability.

He lies smoothly, pretends naturally, and dodges all serious questions aimed at him. The peak of his talent is shown when Mr. Greenleaf hunts him down and proposes an adventurous expedition to Europe to bring back his estranged son.

Ripley accepts and sets on the journey with a dedication that seems unwavering. He quickly assimilates into Dickie’s life and starts living at his home. Marge (Dakota Fanning) smells something fishy, but is too late to reveal her doubts.

The peak of his talent is shown when Mr. Greenleaf hunts him down and proposes an adventurous expedition to Europe to bring back his estranged son.

Ripley works his charm and when it fades, he kills. He kills and steals Dickie’s identity to establish himself as Richard Greenleaf, a signature he practices and practices until perfection.

Ripley kills whenever it gets inconvenient, and elopes. Travelling through cities, forging identities, and shifting between luxury and poverty become the norm for Ripley until he settles in a palace.

With a crystal ashtray and Picasso’s painting (that he chooses not to sell), Ripley establishes himself as a man of taste. His acquired demeanour suits him and we quickly root for him not to be caught. Inspector Ravini (Maurizio Lombardi) is an astute and honest policeman, but too simple to identify Ripley’s intentions.

The importance of art in the show

Art is a character in Ripley. From Picasso’s painting to the light, art inspires Ripley. Dickie has the privilege to drop everything and paint, while he is pitifully bad at it. Ripley is an emotive painter but he is never given the leisure to paint.

Marge is writing a photograph book, a picture travelogue on Atari, and Dickie’s money seems to be facilitating it. At many junctures, the jealousy between Tom and Marge is screamingly obvious. They almost act as the two wives of Dickie and amongst them, Tom wins with a thud and a toss.

They both contest for Dickie’s love, two have-nots craving for the rich man’s attention. Both are freed after Dickie’s death.

They both contest for Dickie’s love, two have-nots craving for the rich man’s attention. Both are freed after Dickie’s death. Marge also goes on to professionally publish her photographs and finally comes out with her book at the very end. A dedication to Dickie on the first page with a picture of Dickie clicked by Marge reveals Ripley’s truth.

The light, always the light

At many junctures, we see Ripley visiting the church and carefully reading a painting. While the audience assumes momentarily that the guilt has pulled him to the church, Ripley has other plans.

On the brink of getting caught, Ripley decides to play with the light. The final act is when the inspector decides to visit him. Ripley recalls every detail from the painting and places the light in a direction that conceals more than it unveils. The art and the light become his co-conspirators and save him in the valour of his final act.

Through his moments of insanity reflecting in the water and through the pure genius holding the plot together, Ripley is a carefully adapted series. It is a perfect thriller for the connoisseurs of great cinema. It is always in the right amount.

Andrew Scott as Tom Ripley is enthralling. The way he emotes a conman’s expressions is just perfect. From his hair to his gestures to the coy lad buying a pair of swim trunks, Scott is a delight. It is him who makes it easier for the audience to root for a conman.

Andrew Scott as Tom Ripley is enthralling. The way he emotes a conman’s expressions is just perfect.

Ripley is a limited series that does not come often. The adaptation is spellbinding and must be watched by the people who crave some serious and scintillating thriller.

Before the inspector’s revelation, Ripley’s final act is when he tells the detective ‘Because he loved me…’ The grain of homoerotic spleen shining through Scott’s eyes while saying this ties all of the series together and makes it par brilliance.

Ripley is like fine wine; it is an acquired taste and must be savoured delicately. It cannot be gulped and wasted.

About the author(s)

Dr. Guni Vats is an Assistant Professor at the Department of English, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies. A PhD in Gender Studies, she is a renowned researcher, writer, and scholar.