The public waits for meaningful feminist cinema and series to enhance the nature of their mundane lives. Feminist cinema is important to foster discussions on what counts as ‘feminist’. In the Indian context, it becomes more paramount to discuss revealing feminist details of Laapataa Ladies, directed by Kiran Rao, that has been in public praise for a month since its release on first March 2024 in India for showcasing the visual reality of the patriarchal system(s) within which women are forced to lead their lives.

Anti-caste feminism is not interested in who gets to be featured on fancy Vogue magazines or Forbes thirty-under-thirty list but it is essentially an exploration of the journey(s) of reclaiming personhood.

Women being forced to lead life in a particular patriarchal manner is what the film focuses on through emphasis on the life stories of two characters–Jaya and Phool, who lead their lives as veiled newlywed female partners on a train journey. Their stories however striking aren’t the focus of the article here. Instead, like many feminists who are in awe with the character of Manju Mai, played by Chayya Kadam, this woman in her late fifties who leads an independent life by powerfully practicing anti-caste ideals is what must be incorporated into our discussion on feminism. Let us explore what is so ‘anti-caste’ about Manju Mai’s character? How does it become a representation of it?

The crux of anti-caste feminism

Anti-caste feminism is not interested in who gets to be featured on fancy Vogue magazines or Forbes thirty-under-thirty list but it is essentially an exploration of the journey(s) of reclaiming personhood. The concept of personhood is contingent upon practicing certain rationalistic moral principles that remain central to anti-caste feminist politics. Anti-caste feminists’ practice rationality that denies upholding the patriarchal double standards.

Interestingly, many girls and women in India partake in performing pretense politics. Pretense politics refers to when women reduce the power of their agency and participate in seeing their life actions only through the binary frames of who is a good woman or a bad woman that targets their bodies and sense of selfhood. It is when women buy the constructed falsehoods to deviate from the real states of their lives so that they can escape being shamed for merely owning themselves and living life on their self-defined terms. For example, women who are not anti-caste in their actions would proudly judge other women for merely owning themselves and their agency.

This list of women is not limited to the rural, in fact it includes many ‘modern-looking’ women who live in South Delhi or South Bombay as well. Women who are not anti-caste switch between practicing feminism and preserving the orthodox traditional religious values simultaneously. These women would often boast about having families that do not allow them to step out late at night or wear modern clothing or boast about being that ‘good respectable woman’ who doesn’t eat non-vegetarian food on Tuesdays but the same set of women would actually do all of the above but refuse to admit it in a public setting.

Women who are not anti-caste switch between practicing feminism and preserving the orthodox traditional religious values simultaneously.

This is what is truly pretentious about feminist politics in India. A second example would be of women who choose partners by themselves and then do everything in their power to dissect the public from calling it ‘love’, especially if they end up marrying the same partner. Their wish is to suddenly call it an ‘arranged’ marriage. The same set of women chose love. They practiced their freedom and agency to choose it but during the moment of legitimisation of their bond, they end up speaking in the language of the pretentious only to be called a ‘good woman’.

Unfortunately, these women don’t reflect on how their actions will impact those who dare to transgress in their respective familial structures and limits, and stand up against the hypocritical double standards that suffocate women’s lives across the globe. They do not even consider reflecting on how they could least ‘test’ their bargaining power, although not in the context where clearly they don’t have any at all. The focus is on those who can exercise and still choose to display complicity.

In their pretentiousness, they bring down the collective efforts of the anti-caste women front, which has a long history of putting their lives on the altar by fighting against Brahminical oppression to be able distinguish the good from the bad in a constitutionally mandated language. Re-defining the distinction of the good and the bad has been an important feature for the anti-caste feminists in the Indian landscape in order to actively advocate for dignity in living. The good and the bad women, who are they? Anti-caste feminists have long argued a good woman is a woman who is free, free from oppression of all kinds and is given the access to liberate herself from any bounded chains holding herself back. While the constitution promises us the same, it is our responsibility to strive to create a collective free society too.

While personal choice of all women must be respected as patriarchal subjugation alters their lived realities differently, this particular act of ‘taking pride’ in being ‘conservative’ is highly problematic for anti-caste feminists who challenge this anachronistic assertion, and claim a womanhood influenced by the moral democratic principles of voicing of liberty, freedom and dignity.

How is Manju Mai an ‘anti-caste’ character in Laapataa Ladies?

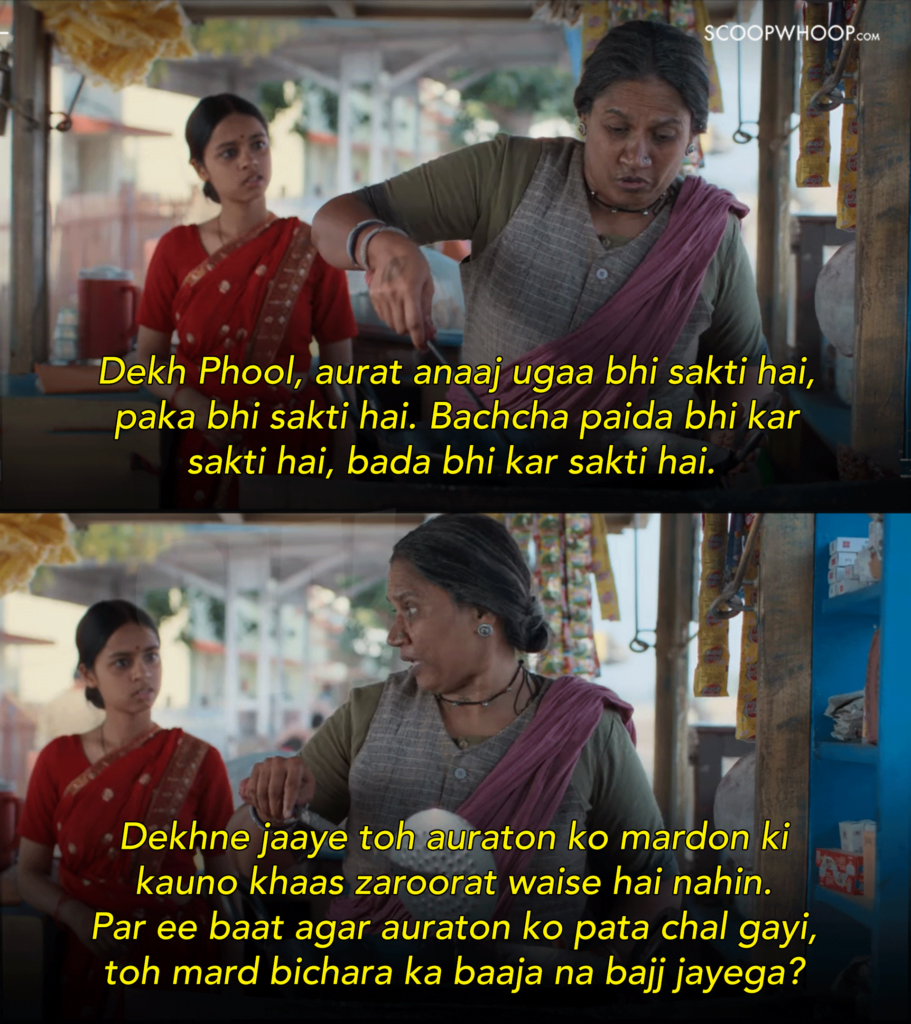

Manju Mai is a reckoning force of engagement with anti-caste feminist politics on the television screens as she reminds the female protagonist in the film of how ‘shame’ and ‘morality’ are used as Brahminical tools to silence women’s agency and voice in India. Manju Mai’s anti-caste feminist politics isn’t limited to the public sphere but extends to the private sphere of the household, where she shares her attempts to bring social change in her life through her self carved decisions as she says to the character of the female protagonist Phool, ‘My husband and son would get drunk and beat me up. And then they would say, a man who loves you has the right to hit you. One day I exercised my right as well’.

This feminist will to transform the private is contingent upon a risk- a risk to revolt, and be seen as the angry ‘mad’ woman who dares to raise her voice against the loud male voice(s) at the Indian household. Her character depicts a lived reality of what happens post a ‘feminist’ and ‘anti-caste’ engagement with one’s womanhood. It is when the burgeoning feminist thoughts project themselves as bolder, firmer and direct. The voice stops shaking as one speaks, and there is a fertile ground of feminist faith one can always fall back on to regain their sense of selfhood and dignity.

Anti-caste feminism transforms the private sphere

Since its inception, anti-caste politics has focused on reforming the private sphere of the household, and the social systems that surround us through an in-ward looking approach instead of an out-ward approach. Dr. Ambedkar believed the progress of a community must be measured in terms of the progress the women of that community has achieved, back in 1950s.

The feminist invitation of Manju Mai extends from her tea-stall to her home where she lives alone, without a family or husband. The welcoming of the unknown other within the private sphere of the household and work has been an integral feature of the inclusive anti-caste ideals as it challenges caste-based segregation in public and private spaces and food practices.

What Laapataa Ladies didn’t say: Manju Mai is a Dalit-Bahujan feminist

Manju Mai confronts the audience with hard-hitting paradoxes reflecting on the patriarchal scam curated by orthodox religious and cultural norms in creating the false notion of a ‘respectable good woman’. She enquires from the female protagonist Phool as she is lost from her in law’s house whether she knows the name of the village where it is situated, and as Phool says she doesn’t know citing that she is a ‘respectable good woman’ who knows how to run a household and sustain it, Manju Mai raises a pertinent point, there is nothing shameful in being a fool but feeling proud of being a fool is shameful.

Manju’s point is clear, how the societal structures benefit from women’s cloaked selves where their identity and personhood take a backseat. Manju Mai speaks a language rooted in constitutional morality where she returns the focus on women’s freedom from relational structures and of being only seen as someone’s ‘mother, daughter or sister’. She says, ‘Women can farm and cook. We can give birth to children and raise them. If you think about it, women don’t really need men at all. But if women figured this out, men would be screwed, wouldn’t they?’

By adding that happiness in solitude is a hard find but once you find it as a woman, you become fearless, Manju Mai is the modern gen-z anti-caste neighbour we all deserve, who would not run to ask your caste but would instead invite you to cook together, have financial freedom and free yourself from the constant burden to conform to soci0-cultural norms without understanding the logic behind them. Manju Mai is the invisibilised Dalit-Bahujan working woman who is always seen as oppressed but contributes immensely to the society she lives in myriad ways. She is not the abandoned poor old woman but the assertive woman who is strong and capable of resisting violence projected at her.

Manju Mai is the invisibilised Dalit-Bahujan working woman who is always seen as oppressed but contributes immensely to the society she lives in myriad ways.

In a world full of elite feminist figures, let us all strive to be Manju Mai in our public and private spheres by abandoning double standards of calling ourselves a feminist if we do not strive to stand up for ourselves and dismantle the moral toxicity surrounding being a ‘good woman’.

About the author(s)

Shainal Verma is a feminist research scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. She is a Writing Urban India fellow and an Institute of Critical Social Inquiry New School fellow. She writes on gender, caste, visual culture, and urban space.