Menstrual Equity is a humanitarian term emphasising empowering the menstruating population by providing appropriate access to period hygiene, sustainable products, and adequate knowledge about monthly cycles. Evolving through activism and fundamental rights, this term focuses on breaking social-moral taboos to encourage open conversations and boost menstrual health consciousness.

The NFHS-5 (National Family Health Survey-5) has unveiled shocking data in its study of 95,551 adolescent rural Indian women. According to the survey report, 58 per cent of adolescent rural women don’t have access to essential products like; sanitary pads, tampons, or clinically approved hygienic menstrual clothes to ensure comfort and cleanness. Revealing the interconnection between literacy rate, financial status and menstrual awareness, the data has also marked out considerable dissimilarities in different states.

In Uttar-Pradesh only 25 per cent of rural women can maintain menstrual hygiene, on the other hand, Tamil Nadu consists of 85 per cent of such female population who can access the basic facilities. Meanwhile, the tribal women stay on the margins of essential amenities during periods that are often interpreted as ‘luxurious and unaffordable,’ things in their communities.

Menstrual equity is a far-reaching goal in India as per the reports of The International Journal of Policy Sciences And Law. In our country, “Only 12 per cent of the menstruating population has adequate access to period products. The remaining 88 per cent is largely dependent on unsafe alternatives such as rags, cloth pieces, leaves et cetera,” it states.

The lack of minimum facilities during menstruation comes with horrifying side effects and goes against the “Right to Equality” and “Right to Life and Liberty” under articles 14 and 21 of the Indian constitution. The “Maneka Gandhi V. Union of India” case highlighted that life is a matter of “living with dignity” and living like an animal or somehow maintaining a physical existence can’t be classified as a dignified life. The current miserable state of poor menstrual facilities and the tumbling stage of required awareness do not match with the directive principles of state policy and Articles 28, 45 and 47 that promise the welfare of all the people, childhood care and education, and promotion of public health.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals have also voiced concerns against discrimination in menstrual health services. Therefore, it’s not possible to ensure human rights and social justice without attaining period equity.

Why does ‘period poverty’ still exist?

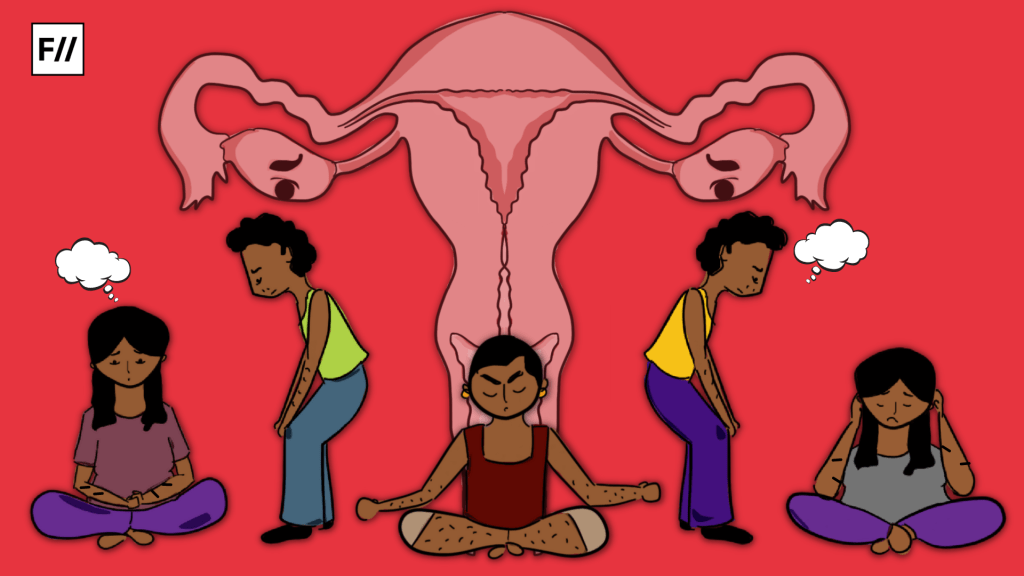

The first step to accomplishing menstrual equity embarks with the efforts of eradicating period poverty as the inaccessibility of sustainable menstrual products and the moral stigma around it are global obstacles. In numerous parts of India, women still use ashes, newspapers, husk sand, and dried leaves for blood absorption. Most women use homemade cloth pads that are often dirty and unhygienic. Such unfortunate options doubled by moral stigma increase the risks of physical and mental health hurdles for the menstruating population.

The reason behind the present scenario lies in the financial ‘insufficiency,’ of the women to afford menstrual products like sanitary napkins, tampons and WASH facilities that include the management of water, sanitation and hygiene. Due to the mounting price of these services, and the lack of women’s toilet and water resources, most women struggle to implement simple health guidelines during periods. Women also remain deprived of the adequate nutrition and good atmosphere they require to manage the cramps, pain and mood swings.

Apart from the high-cost production of period products and financial reasons, the unsatisfactory legal procedures, arbitrary administrative approaches and absence of a better disposal system are other primary reasons behind the miserable condition. Precisely, the upright approach to the menstrual cycle is directly linked to financial stability, education and locality.

The Indian government started the MHM scheme (Menstrual Hygiene Management) in 2011 to improve pad distribution programs with ASHA workers but it has not made any significant change till now. In October 2023, Bombay High Court highlighted that the central and state governments have not worked effectively in implementation of the MHM initiative and these failures have caused more hazards for women and adolescent girls. Meanwhile, unfunded mandates, lack of proper training and stigmatisation of the issue has failed the other governmental sanitary pad distribution initiatives under RKSK (Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram scheme, Uttar Pradesh), VHSNC (Village Health, Sanitation, and Nutrition Committees, Bihar), the related ‘Mamta Samitis,’ and other policies.

However, the government has removed the previous 12 per cent taxation on sanitary napkins but the raw materials required for production like polymer, polyethylene film, glue, release paper, packing cover, wood pulp and thermos are not free from the burdens of taxation. Apart from this, the available sanitary pads in the market don’t ensure health and safety during the menstruation phase as the harmful properties of 25 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have been reported in different sanitary pads that can cause serious health difficulties.

Menstrual illiteracy and cultural taboos

Women are often trapped in cultural and social taboos that decipher menstruation as an ‘impure,’ thing. Apart from the ban on kitchen activities, alleged auspicious places and religious chores, women are also prohibited from touching particular foods, plants and holy books. Indian social set-up believes in ‘purification bathe,’ to rejoin the normal routine after menstruation, while some regions compel women to leave home and live in animal sheds, causing more isolation and anxiety for them.

Most teenage girls and young women don’t know about the science of periods and their bodies. This ignorance doubled by lack of facilities and clueless taboos demotivates the governmental workers, corporate sector and academic institutions to do the needful. Due to the miserable state of awareness, despite brutal discrimination and suffering, women have not welcomed the steps to break the taboos. Numerous teenage girls drop out of their education due to the lack of toilets at schools because managing the menstrual cycle in such a situation brings more hazards and shame. A survey of 1,967 governmental schools claims that 40 per cent of toilets in such infrastructures remain unused and around 72 per cent of toilets lack water and sanitation.

The conservative silence on the issue makes it difficult for women to manage errands at work because they feel uncomfortable expressing difficulties. Sexist systems have repeatedly used menstruation as an irrational excuse for discrimination in providing better educational and work-related opportunities.

However, some localities celebrate the first menstrual cycle of young girls but it does not stop the hush-hush behavior of society. To normalise menstrual cycles and attain social justice women don’t need divine stories and man made rules. Humanising the period is the only way to reach equal rights and make them feel comfortable in their personal and professional spheres.

Toxic positivity, period sabbatical and possibilities of change

Television advertisements showing women jumping-leaping and super happy after using a specific product impose the idea of unrealistic expectations through toxic positivity and double standards. Women shown in Indian sanitary napkin advertisements encourage the culture of mumbling the issues in a concealed way that is based on blocking the possibilities of progressive waves.

Civil societies and feminist interest groups have also been raising demands for 2-3 days’ menstrual leave to ensure better inclusivity. Menstrual Health Products Bill, 2022 has presented the roadmap of 3 days of leave for women however several leaders from the ruling party have been opposing it with anti-women narratives. To establish menstrual equity, we need to strengthen education, boost awareness and reinforce open conversations. Egalitarian policies, better financial planning and a humanitarian governmental approach are obligatory for proper infrastructure, toilets, WASH amenities and sustainable sanitary napkin options to establish the woman’s right to respectful menstrual cycles as an essential human right.

Women don’t require phoney glorification but a sensible system and social justice to understand their necessities. Menstrual cycles need to be taken as an honourable crucial natural process of life and not as something impure. When the possibilities of change arise at the forefront, the dream of justice will come true.

About the author(s)

Mariyam (she/her) has a thirst for significant stories that consist of humanitarian and feminist themes. She comes from Journalism, English Literature, and Political Science academic background.

For her, words are a visionary sovereignty to stand on and find the meaning of being while journalism is the only place where truth comes with facts and data. She also likes documentary photography, Rumi's spirituality, dreaming, and stargazing.