What has been the relation between women and the night? Women have either been heavily policed at night by state authorities, intimate partners and often in fact themselves or been subject to various forms of attack. It was as far back as in 1877 England that we have the first recorded history of Take Back the Night protest, an event organised by women to protest against the lack of safety in the streets of London.

The first Take Back the Night march happened almost a century later in 1978 in San Franscisco to protest violence against women. Since then, Take Back the Night events and rallies have become powerful symbol of protests for women and in many cases sex and gender minorities against gender-based violence that they routinely encounter in the various sites of their lives.

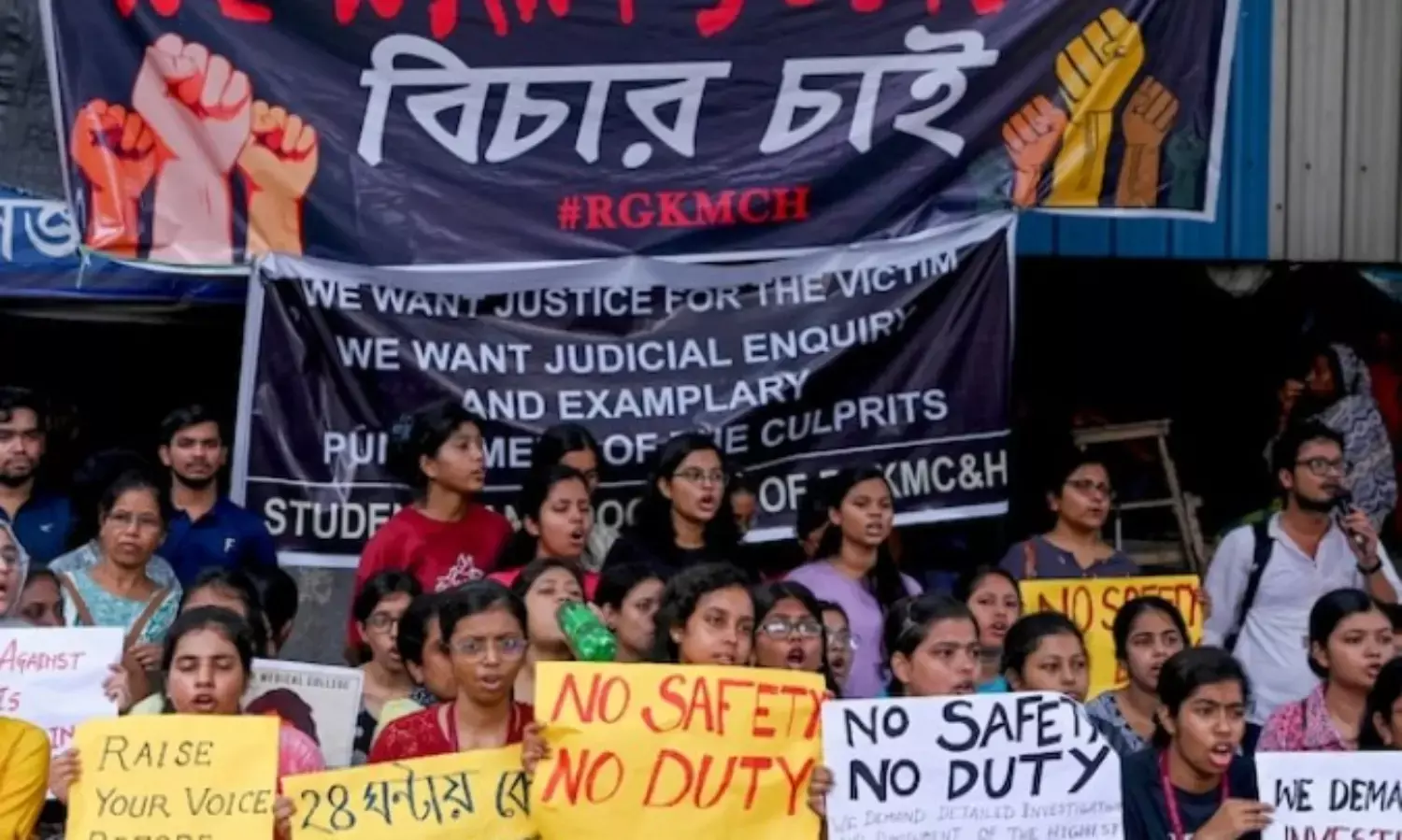

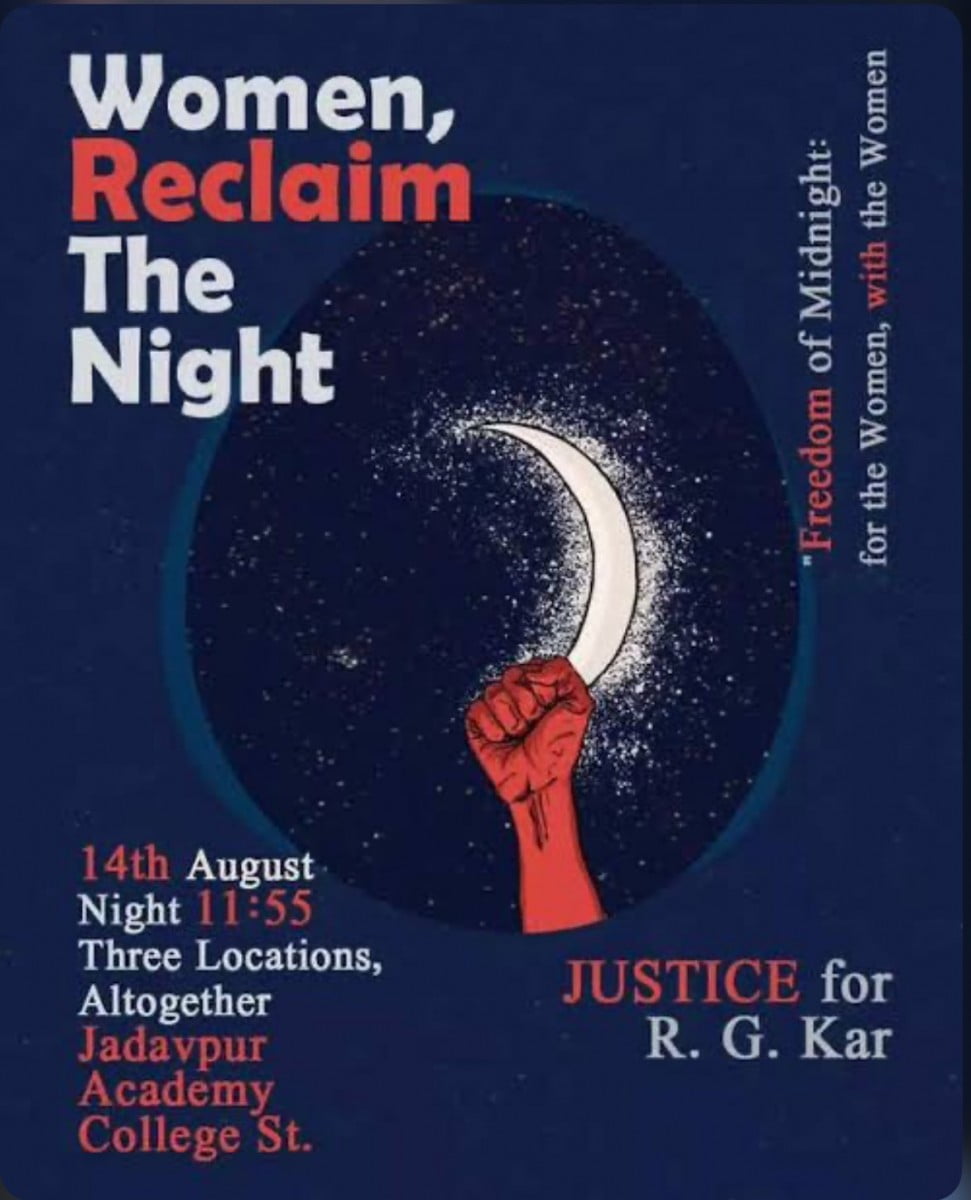

In the aftermath of the horrific incident in RG Kar on 9th August and the outbursts of protests and anger, groups of feminist collectives issued a call for women and queer persons to occupy the streets of night time Kolkata at the stroke of midnight on India’s 78th independence.

In the aftermath of the horrific incident in RG Kar on 9th August and the outbursts of protests and anger, groups of feminist collectives issued a call for women and queer persons to occupy the streets of night time Kolkata at the stroke of midnight on India’s 78th independence. This call to Take Back the Night references this history of the movement of the marginalised genders to reclaim spaces where they have been policed, abused or restricted for centuries.

The call quickly resonated with women and gender-sex minorities across the state. What was to be centralised in three sites in the metropolis quickly took a life of its own with vigils being planned not just across the city but also in smaller towns all across the state. While the immediate aim of the call was to protest and call for speedy redressal/justice for the heinous crime, the protest also raised questions about women’s safety in public spaces at night. And it is in relation to this more general, implicit point that this particular protest cannot be seen as gender neutral.

The night guardians

The idea of a woman and gender-sex minority protest springing up all over the state was, however, lost to a vast majority of cis-men who turned up in large numbers to these events equaling and sometimes even surpassing the other participants numerically. For some it was the issue of guardianship, of protecting their wives, mothers, sisters, daughters who would come to the protest and for others it was a question of showing solidarity.

The presence of non-male bodies in public spaces is conditioned through purpose and time. Women’s encounter with the streets can only be legitimised if there is a purpose to it, a purpose of reaching a destination, walking ideally at a brisk pace and essentially in broad daylight. Loitering the streets in the night time city spells deviance, a deviance to be disciplined through sanction, shaming and violation. In their book Why Loiter written in 2014, Shilpa Phadke, Shilpa Ranade and Sameera Khan argues for loitering as an act of defiance, an act to claim public space and therefore inclusive citizenship.

It is the revolutionary potential of this small and seemingly banal act of an ordinary woman loitering and occupying the streets that lies at the heart of the Take Back the Night movement.

It is the revolutionary potential of this small and seemingly banal act of an ordinary woman loitering and occupying the streets that lies at the heart of the Take Back the Night movement. A survey by a Delhi based NGO Breakthrough in 2021 showed that 78% women experienced violence in public places. Elkin writes that women in cities are viewed through three lenses—as objects of desire, a body for sale and a form of public exhibition.

It is only male guardianship that otherwise authorises women’s presence in these spaces. The relational mapping in the guise of mother, daughter, wife or sister is the only lens in which patriarchal spaces of the city can be safe access points for women, though as we consistently see male guardianship is no guarantee for safety. The irony of the figure of concerned well-meaning male guardian protecting their women as they seek to reclaim their city, their nights defeat the very act of subversion.

Further who are these male guardians? National Crime Records Bureau (2022) reports 31.4% of crimes against women are perpetrated by husbands and their kin. National Family Health Survey-5 (2020-21) shows 29.3% of ever-married women aged 18-49 have faced violence at the hands of their husbands.

The site of the family thus has been seen time and again to be one of violence against women. Juxtaposing the unsafe streets with the safety of the home ironically plays into a patriarchal framing which seeks to emphasise this very point to legitimise women’s restricted access to the public space. Safety in public space is closely linked to women’s security in their own homes and therefore the uncritical acceptance of moral responsibility of guardianship needs some rethinking.

Solidarity and allyship

Then comes the question of solidarity. No one owns a protest especially spontaneous one but a huge male presence defeats the very metaphor of gendered bodies in hostile spaces. Solidarity with those more marginal to you is not an exercise of spontaneity but of unlearning the privileges built into one’s psyche and making an effort to do the right thing. In a country where women spend over six hours on an average doing unpaid housework where their male counterparts do less than one hour, imagine what that night would look like where women and gender-sex minorities took the street and men took care of the home.

Yes, that is what allyship looks like. Instead of outshouting the women in sloganeering, jostling to reach the top of the rally that silent support would have been that much more powerful. Black feminists and Dalit feminists argue that claiming universal sisterhood without any reference to politics of domination based on race or caste is merely a way to appropriate or render invisible the claims of the most marginalised. Just like famous celebrities or poets telling women how to feel in the wake of such gruesome crimes, this push for gender neutral equal claim to the streets re-enacted or at least sought to re-enact domination.

Two steps forward, one step back

The question that follows then is, was the protest then a failure? The immediate and short-term answer is no, it created momentum, it created acute pressure for accountability. But at a time when the entire public sphere is rightly pushing for state accountability, of structural changes, the reclaiming night moments provided an immense possibility of first steps to a societal change.

A truly revolutionary moment was diluted, a moment where women and gender-sex minorities could lay claim to ownership over hostile spaces and temporal policing, the metaphor of independence, the possibilities of building collectives and with that was lost a promise of structural- attitudinal changes; changes which in the long run could create a bulwark against heinous violations like this in more effective ways than the present blood curdling call of retribution.

More importantly lost was a lesson of solidarity, of learning to cede place in order to walk together, of unlearning entitlement to learn to be better allies. If indeed women and gender-sex minority people could have occupied and dominated the night streets on that night, would the West Bengal government retain the audacity to suggest reducing women’s access to night as a shorthand for their protection?