Bengali cinema witnessed a long-standing tradition of portraying avant-garde thinking on the silver screen. Films written and/or directed by the likes of Satyajit Ray, Rituparna Ghosh, Aparna Sen and Kaushik Ganguly are known for their nuanced narratives on gender and sexuality. Mainstream commercial films, however, continue to cast women in subservient roles and as romantic interests with little to no dimension or autonomy.

Amidst these, some timeless and recent films have portrayed exceptionally moving women leads, which challenge patriarchal institutions and rewrite the possibilities of imaginative self-expression. The growing number of films with strong female leads addressing varying social issues promises the possibility of more nuanced characterisations of women in Bengali cinema.

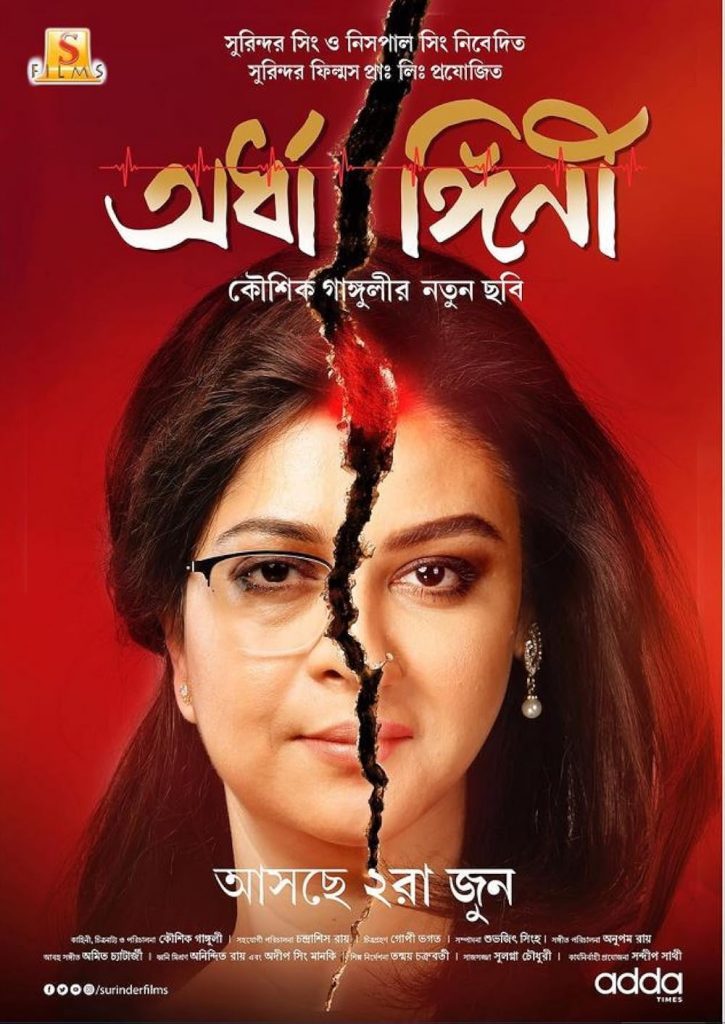

Ardhangini (2023)

Kaushik Ganguly’s Ardhangini tells the story of Subhra (Churni Ganguly) who is forced by her circumstances to collaborate with the wife (Meghna played by Jaya Ahsan) of her ex-husband Suman (Kaushik Sen) to save his life. New to the country and the city, Meghna seeks Subhra’s help to gather information about Suman’s health insurance and bank accounts. Through the consequent interactions between Meghna and Subhra, the film reveals Subhra’s emotional turmoil and conflict.

The most commendable aspect of Subhra’s characterisation is that it is free from all pretences. The writer-director carefully presents the multiple facets of Subhra’s character which defy patriarchal codifications. Subhra experiences a range of emotions – stemming from the moral need to save Suman and her awkward interactions with the Meghna. Time and again, Subhra clarifies that Meghna must not put her on a pedestal for helping her. Her anger, jealousy and frustrations often surface as (unjust) outbursts at Meghna, who is now enjoying the security of a marital life with Subhra’s ex-husband.

Towards the climax of the film, when Meghna thanks Subhra for her help, saying she won’t ever be able to repay her debt, Subhra promptly replies, “Ta bolle toh hobe na. Prakton stree mohajon er moto. Shey jane shey tar capital ta konodin pabena. Shud ta toh tomake chukiye jetei hobe shara jibon.” (That won’t do. Ex-wives are like moneylenders. She knows she will never earn her capital back. You will have to keep repaying the debt for the rest of your life). Subhra’s character therefore defies black and white categorisations. While she displays the strength and ability to break her marital ties when the relationship soured, she simultaneously is humanised by the depiction of her yearning for the same.

Kuler Achaar (2022)

A light-hearted family drama, Sudeep Das’ Kuler Achaar scratches the surface of the feminist ideals of reclaiming one’s identity and self-representation. The film highlights the various curveballs women face if they choose to keep the surname they grew up with after marriage. Situated within an orthodox family and society, Mithi (Madhumita Sarcar) faces several criticisms from her father-in-law due to her decision. In a surprising turn of events, her mother-in-law, Mitali (Indrani Halder) vows to follow Mithi’s suit. As Mithi begins to understand the benefits of sharing one’s husband’s name in a patriarchal society, Mitali grows surer of her choice to change her name.

In a desperate attempt to prevent her from changing her name, Mitali’s husband comes up with a list of expenses that he has had to bear in the years of their marriage. However, Mitali remains undeterred, listing all the ‘free,’ services that she provided for the family, demanding a monetary settlement for the same. The film draws attention to women’s unpaid labour and presents a picture of some of how contemporary women choose to define themselves.

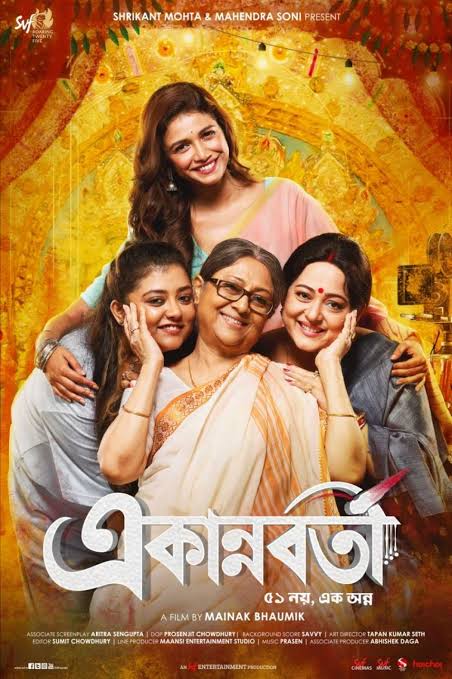

Ekannoborti (2021)

A story that spans across three generations of women brought together by the festival of Durga Puja, Ekannoborti explores the lives of four women battling the chaos of their own lives. This Mainak Bhaumik film sheds light on broken familial ties, body dysmorphia, the difficulty of ending toxic relationships and relearning the meaning of love.

Over the course of the film, the middle-aged character Malini (Aparajita Adhya) comes to terms with her failing marriage and finds a new companion in Abhradeep. Malini’s daughter Pinky (Ananya Sen) suffers from chronic body dysmorphia and interprets any male attention as a joke or fetish. When Pinky recovers after attempting suicide, Malini’s poignant monologue identifies beauty as a patriarchal construct, “Cheharaey ki ashey jaey, Ma? Lomba, bete, kalo, phorsha – egulo shob biyer dhop, Ma. Tui ki patri chai biggapon e model hobi? Tahole? Kichu tey kichu ashey jaeyna.” (Appearances don’t matter. Tall, short, fair, dark — these are all constructs of marriage. Do you want to be a model in a matrimonial advertisement? Then? None of these things matters).

Pinky’s character brings forth the much-needed representation of a plus-size woman in Bengali cinema and establishes the necessity of therapy and emotional support for people battling mental crises. It encourages positive dialogues surrounding awareness about mental health and how parental figures can support and ease their journey of healing.

Women, marriage market and Sweater (2019)

Written by Joeeta Sengupta and directed by Shieladitya Moulik, Sweater tells the story of a girl named Tuku (Ishaa Saha) whose parents are obsessed with the idea of instilling new qualities in their daughter to make her more appealing in the matrimonial market. Frustrated with the multiple taunts and rejections, Tuku decides to challenge the narrative by learning to knit. Her quest to learn knitting led to a trying but fulfilling journey of self-discovery that ultimately gave her the confidence to discard those parts of her life that were holding her back. She says goodbye to her partner Pablo (Saurav Das) and in a final assertive scene pays him back for all the dates they had ever been to.

Though her knitted sweater passes the inspection of the mother of her marriage prospect, Tuku chooses to turn down the offer. The film ends on the positive note of Tuku’s self-discovery, unmarred by the conventional expectation of a ‘happy-ending,’ achieved through a heterosexual union or marriage.

Iti Mrinalini (2011)

Aparna Sen’s Iti Mrinalini explores the life of a Bengali actress who reminisces on her youthful years while contemplating taking her own life. Played by Aparna Sen and Konkona Sen Sharma, Mrinalini’s character delves deep into the various forms of crises women face in their personal and professional lives while in the entertainment industry. Mrinalini’s affair with a prominent and married director as a rising actress becomes a reason for a series of disappointments in her life. She chose to go through a resulting pregnancy alone and offered her daughter to be adopted by her brother and sister-in-law living in the States.

The film focuses on Mrinalini’s never-ending, never-quenching search for love. Though all her relations came to unfortunate ends, a platonic friend’s reminder of his unconditional love for her deterred her from giving up on life. The end of the film leaves the poignant message that domesticity is not the only way of achieving fulfillment and love in life.

Women and familial relations in Unishe April (1994)

Rituparna Ghosh’s Unishe April revolves around a mother-daughter duo who share a strained relationship with each other. To avoid facing her failing marriage due to her growing popularity and success as a classical dancer, Sarojini (Aparna Sen) chooses to devote herself entirely to her art. As a result, her daughter Aditi (Debashree Roy) feels neglected by her mother throughout her formidable years and idealises her father as the ideal parent.

The duo’s relationship is embittered further when Aditi is sent to a boarding school upon her father’s untimely demise. Aditi’s homecoming opened the old box of anger, frustration and grievances that she held against her mother. The film explores the life of a woman belonging to the performing arts background. It challenges the patriarchal codification of artistic professions.

Unishe April delves deep into the problem of villanisation of the working women by their family members and the additional pressure to choose either work or family. The ending of the movie positively asserts the possibility of the coexistence of both.

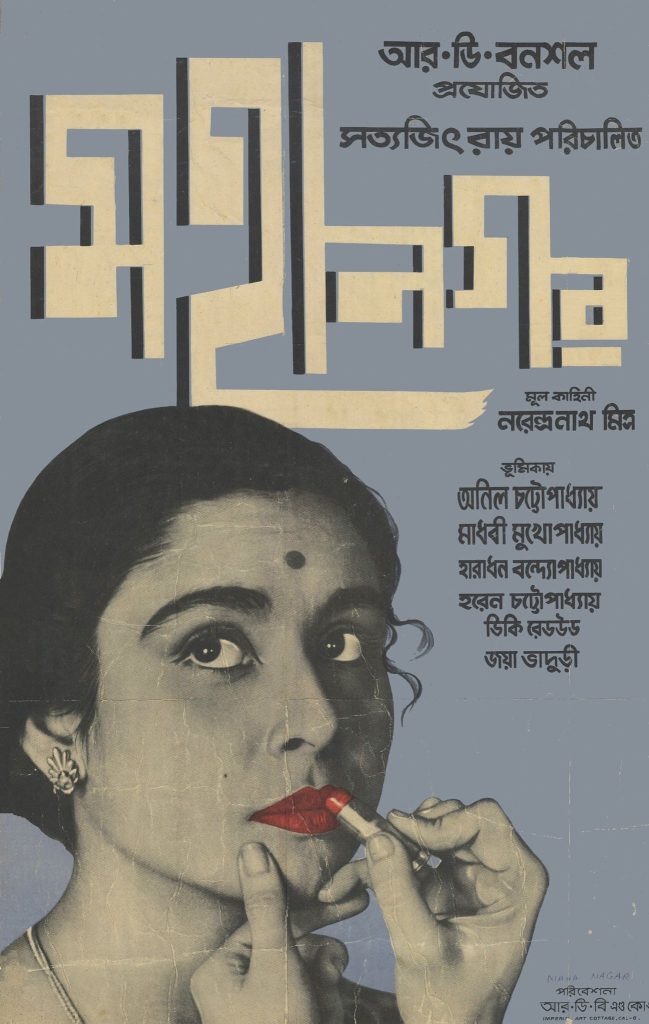

Life of a working woman in Mahanagar (1963)

A film that was much ahead of its time in its representation of a working woman, Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar tells the story of a saleswoman Arati (Madhabi Mukherjee). Yearning to help her struggling husband financially, Arati decides to take up a job until her husband finds a part-time job to supplement the family income. However, her interactions with the people of the city and her women colleagues boost her confidence. She discovers new means of self-expression, such as fashionable sarees, red lipstick and sunglasses which makes her erstwhile supportive husband grow insecure. Fighting against societal dictates and the rigid patriarchal norms that limit women to domestic spaces, Arati finds joy in her work, excels and is rewarded for her success with commissions and raises.

Bengali films have come a long way in their portrayal of women. Though stereotypes continue to feature, films like these present a broader spectrum of women’s everyday experiences and validate their struggles through effective, sensitive and relatable representation.

About the author(s)

Madhusmita Mukherjee (she/they) is a queer feminist writer and photographer from Assam who is passionate about advocating gender equality and social justice. She completed her postgraduation in English from the University of Delhi (2022-24). Her academic interest lies in gender studies, media memory and cultural studies. Her recent publication features in the Zubaan anthology Riverside Stories: Writings from Assam edited by Banamallika.