December 31st, 2016. I lived in the rural town of Surat on the banks of the Tapi River. Less than a year after graduation from college, still learning to be ‘out in the world,’ I stood at the intersection of an existential spiral and the fresh wound of a sexual assault that was seeping deep into my subconscious. Around noon, I decided that I could not spend the New Year’s Eve boxed up in my room. I must go somewhere, I must travel and do something that gives me hope.

The first solo travel

And so, I started walking to the nearby tea stall on the highway, trying to enquire around and make up my mind. With a sense of resolve, I took my bag and wallet that carried Rs 600 and headed for a hill station at the border of Gujarat and Maharashtra that I had heard about locally. It was a day of travel, and I planned to return before midnight. It was the first time I was solo travelling. I was used to travelling between places unaccompanied but had never visited a place where I did not know another soul.

I took a transit bus to the central town from where I boarded the bus to my destination. I was instantly identified as an ‘outsider,’ from my appearance and language. A woman sitting next to me, probably in her 40s, started making small talk with me. She introduced herself as Ayesha. As soon as she learned where I was headed, she informed me that it was the wrong bus. I didn’t take her concern seriously initially, thinking that I would change the bus if that was the case, being the street-smart person who can always figure a way out. But soon my nonchalance turned into dread. As it turned darker, the green and serene countryside put on a grimmer appearance. The female passengers kept decreasing and suddenly the bus was filled with young men. I felt their piercing gaze on me, and it was very clear that I didn’t belong there.

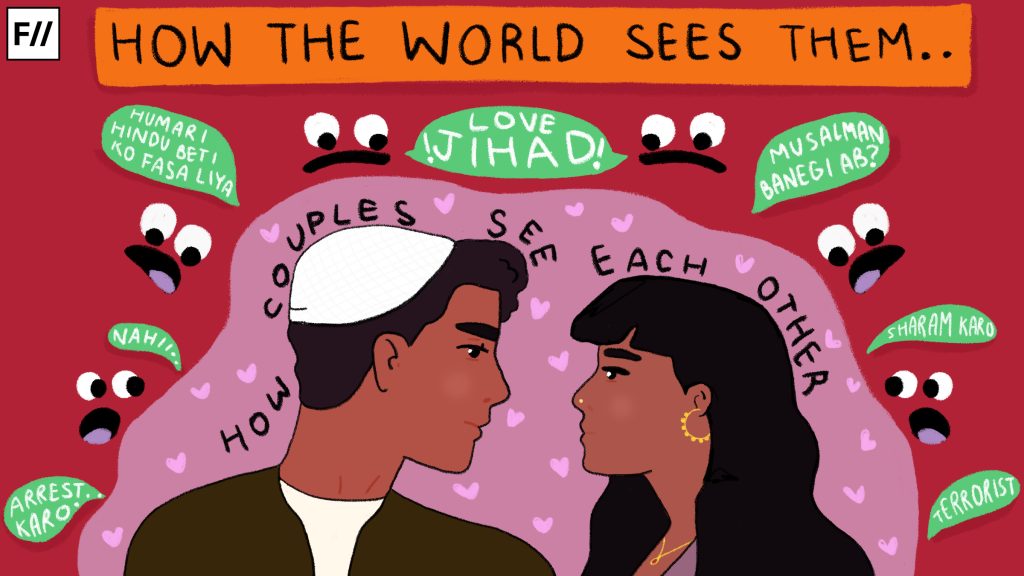

It was still early back then, and I was oblivious to the kind of islamophobia that consumed our social and political lives. In the coming years, living in a society burning with hatred, amidst the intensifying hate campaign against Muslims in the media, the love-jihad theory gaining popularity, mob-lynchings, abrogation of Article 370, CAA protests, echoing prejudice around me in family, community, relatives, friends and colleagues, I was baffled and kept wondering what led to this collective psychosis. How did we manage to dehumanise a group in such a way that all exclusion seemed justifiable?

Ayesha had frantically started an intervention for me, calling her husband to ask about the routes, discussing with other women sitting nearby, and talking to the driver for confirmation. Amidst all this, I realised I was badly stuck- I could not find any bus to go forward or to return at this hour (it was past 8 pm), it wasn’t a city where I could find hotels, not that I had money for overnight stay and there was no system of instant transfers that I could have asked a friend to pay on my behalf.

In that mess, this kind stranger emerged like an angel to save me. Ayesha offered her place for me to stay overnight and promised to put me on the first bus to my destination in the morning.

Breaking down the cultural barriers

As we got down at the bus stop, in a town I knew nothing about, she asked me gently, “You will be okay eating our food?” I was taken aback and embarrassed at the same time. What was the power dynamic between us? Wasn’t I at her mercy and should have been the one to apologise for causing inconvenience? Yet she took it upon herself to check if I had any inhibitions of purity considering our different religious backgrounds.

It spoke volumes about the unwritten social code in Gujarat, a society that is neatly segregated along communal lines. Hindus and Muslims coexist but on either side of the demarcation. Peace and harmony are achieved not by appreciation of different cultures, but by keeping away from ‘those who are different from us.’

It was still early back then, and I was oblivious to the kind of islamophobia that consumed our social and political lives. In the coming years, living in a society burning with hatred, amidst the intensifying hate campaign against Muslims in the media, the love-jihad theory gaining popularity, mob lynchings, abrogation of Article 370, CAA protests, echoing prejudice around me in family, community, relatives, friends and colleagues, I was baffled and kept wondering what led to this collective psychosis. How did we manage to dehumanise a group in such a way that all exclusion seemed justifiable?

While the rise of right-wing sentiment with the orchestrated efforts of a right-wing government is responsible for religious polarisation, the existing practices of spatial and cultural segregation enabled it. Our society is structured such that even when different communities live in proximity, they are known only through the broad strokes of what has been heard in the media, the information (assumptions) that have been passed down through the generations.

As a child, I often heard whispers like ‘we should not get close to them,’ and ‘they are not like us.’ I never understood why and did not have adequate opportunity to understand better. In the present, I have understood that this ‘othering,’ at the micro level has played a role in fueling mass communal hatred in the country. When labels like ‘anti-national,’ ‘jihadi,’ and ‘Pakistani,’ are evoked, most people cannot conjure up a familiar face behind these labels. As Muslims are absent from the daily social and cultural lives of the majority population, it is easy to invisiblise them from our imaginations. Our paths never intersect. Seeing each other, on the streets, in the markets, but still unfamiliar. And thus, we continue living in our confines, with invisible high walls separating us.

These walls are built on three things- one, the difference in food habits, non-vegetarian food being tied to Muslim identity and the idea of purity and pollution prevalent in the Hindu caste system. Two, the conversion conspiracy, the notion that through romantic persuasion or by participating in their culture, Muslims will convert you to Islam. Three, the regressive belief system, the notion that the Muslim culture is regressive, patriarchal and oppresses women.

If there is one thing my travel experience taught me, it is the expression “just like me.” That is what I felt after meeting Ayesha, she is just like me. The familiarity feels like home, even if our lives were different in so many ways. I have felt such camaraderie and a sense of community with several women I have met on journeys. This is the key to scaling the high walls of segregation in my view. Knowing each other. Creating shared experiences of life.

Cultivating a community of love through travel

At Ayesha’s place, I met her daughter who was only a couple of years younger than me. She shared about her life with me as we had dinner together. A cousin joined us later and we went out to have ice cream. At night, the girls watched Cinderella, a film I was quite fond of. Quite exhausted from the eventful day though, I got inside the heavy quilt, closed my eyes and overheard the familiar dialogues. At midnight, I heard the fireworks outside. It was New Year. I wanted to go out and watch, but the bed was too cosy and warm. So, I just drifted to sleep. At last, I did have a hopeful New Year, not the way I had imagined it to be, but certainly memorable.

The next morning when the alarm rang, I wished I didn’t have to go. I wished they would ask me to stay back if I liked. It was too comfortable, and I wanted to sleep in. But as promised, Ayesha woke me up at 5, got hot water to wash up and prepared tea for me. She walked me to the bus stop and only left after putting me on the right bus. I finally did reach my destination, spent the day sightseeing, hitchhiking from one place to another and ended it with a beautiful sunset. It seemed that everyone in that small town, from the bus stand to the food stalls to the tourists got a whiff that a non-Gujarati girl had come all alone. All alone! No man with her! Not even friends!

I met with a lot of curious prying minds, but everyone helped me. Interestingly, the protectiveness also came from a patriarchal frame. “I will ensure you return safely. You are like my sister,” exclaimed the stall owner at the bus stand who knew all the bus schedules, drivers and conductors. Nevertheless, this travel worked out for me.

Over the years, I travelled to different places, took longer solo travels, met people, and lived with different communities across the country. No matter what our differences in culture, aspirations and way of life were, I always found a connection with people based on mutual respect and moments to share warmth and love were abundant.

In that sense, travel has been a teacher for me. I have learned cultures; I have learned love and generosity. Now, I have many homes, instead of just one, and my family extends beyond the ties of blood, kinship, language, and geographical space.

Years later, in 2023, I travelled to Srinagar and chose to stay with a local Kashmiri family, drowning out all the voices of fear echoed in the mainstream narrative. I realised then, that the seed of love and trust was sown in my heart long back.