The doctrine of justice demands an unprejudiced and independent judiciary. Likewise, a judicial exercise of power is expected to be free from “fear and favours,” to be uninfluenced by biases and stereotypes, and to maintain prudence to maintain the sacredness of the institution of judiciary. The judicial system encapsulates the values and ideas of a society by enforcing the system of law to the best of its capacity. Therefore, in doing so, it also strengthens and empowers the belief system of a society, sometimes even stereotypes.

Judges are supposed to be free and fair. It is with this faith in their prudence that they personify justice in essence and carry the responsibility of being just without any undue influence. Though most judges endeavour to steer clear of their inclination towards subjective satisfaction and believe in making decisions liberated completely from an external influence of subconscious factors like religion, caste identity, gender, and so on, this may in some cases lead a judge to make a factual determination on unjust grounds.

The Indian judicial system is afflicted by a patriarchal worldview with archaic and insensitive views against women and people from sexual minorities. Acknowledging the fact that it is a patriarchal society in which we live, the judiciary must have a perspective on the same. Ironically, patriarchy persists within the system, which seeks to end such practices as well. Through its legal rulings, the judiciary has reflected the progression of society. Although not infallibly, the Indian judiciary has aided women and the LGBTQ+ community in obtaining what is due to them as a matter of right and has demonstrated that discrimination against them in Indian society would not be allowed.

Exploring the multitude of biases present within a singular courtroom

A courtroom is a place that challenges any stereotypes, injustices, or tyranny and pits down any social, political, or economic dominance. Courtroom bias may exist in various forms. It may be towards the administrators of law or even towards the citizens within the courtroom.

Women in law is not a known genre. Just as in the real world, males dominate the judicial world as well. From clerical staff to judges and lawyers, women are nowhere to be seen. The ratio of female judges remains as low as 36 per cent the number only decreasing as we move to higher courts.

Nearly half of the applicants taking law courses are women, either through the Common Law Admission Test for National Law Universities or at State/Central Universities. Regardless of the same rate of applicants, women attorneys are a rarity, and most face verbal assaults openly.

Quite recently, in September 2024, High Court Judge, Justice Vedavyasachar Srishananda, was seen on video making a sexist and derogatory remark to a female lawyer. The video showed the judge being agitated by the initiative taken by the female lawyer asked by the opposing male lawyer. The judge said that she (the female lawyer) seemed to know everything about him and may even reveal the colour of his undergarment if asked.

Law and justice are considered matters of rationality and prudence. Societal stereotypes and views often do not consider women as rational, logical, or even capable, resulting in barriers at workplaces and being deprived of opportunities and responsibilities. According to the Economic Times Legal World, out of 719 sitting high court judges of all Indian High Courts, only 99 are women. Madras High Court (HC) has the highest, with 14 out of 66 judges being women, followed by Punjab & Haryana, which have 13 women judges out of 54.

For the apex court, appointments are made from the pool of High Court judges; however, a lack of representation in the HC also transfers to a lack of representation in the SC. On the contrary, as per data for 15 States provided by the Bar Council of India, there are 2,84,507 women lawyers enrolled out of the total 15,42,855 advocates, accounting for 15.31 per cent yet out of this number, a mere 99 were elevated to justices.

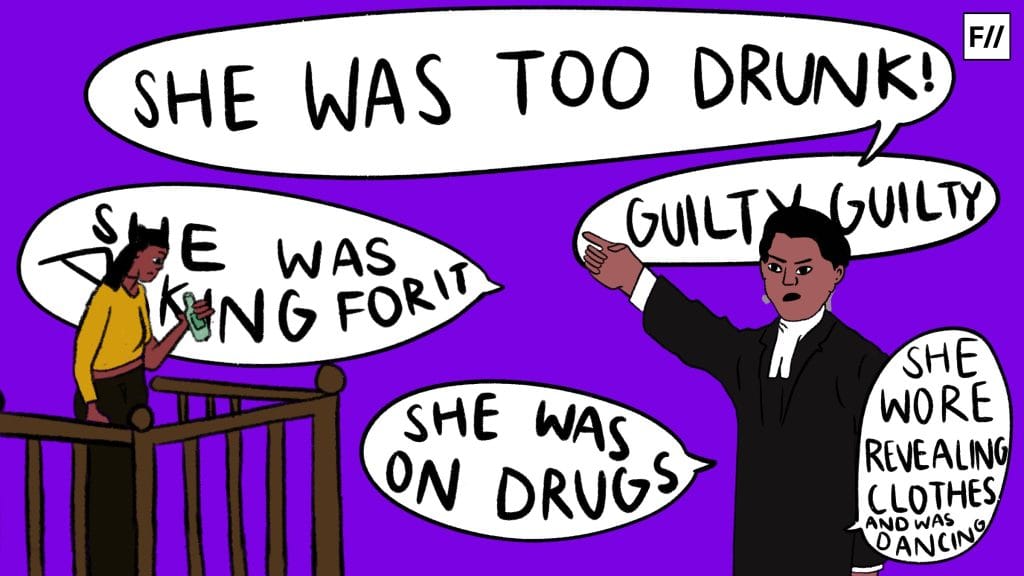

Biases exist not just against women within the judicial system. Manifestations of courtroom bias can be witnessed most frequently in cases of family law and criminal law concerning the treatment of the victims of crimes such as domestic violence and rape. There are numerous cases that can be taken as an example of such a display of bias. For example in multiple cases of divorce, the courts have quoted appalling statements such as, “A wife should be minister in purpose, slave in duty, Lakshmi in appearance, Earth in patience, mother in love, and prostitute in bed.”

Diverting our attention to the gender bias faced by the LGBTQ+ community, high court judge Justice Pankaj Jain flew into a temper when he came across a same-sex case of a petition filed by a 23-year-old woman whose 19-year-old partner was being kept captive by her parents in UP. “Is this a queer couple matter?…take this immoral thing back where it came from,” the judge remarked in the open court, throwing the file.

Another speculation is of the advocate Saurabh Kirpal. Saurabh Kirpal is a senior lawyer and an LGBTQ rights activist. He was unanimously recommended by the Delhi High Court Collegium on October 13, 2017, and was approved by the Supreme Court Collegium on November 11, 2021. The collegium reiterated the proposal, revealing that the objections against Kirpal were that his partner is a Swiss national and that Kirpal “is in an intimate relationship and is open about his sexual orientation.”

There is no official data for sexual minorities within the judicial system, but it may be that due to these very apprehensions and social stigma, people may not be comfortable being open about their sexuality.

Just as with sexual minorities, there are no official numbers for the representation of scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and other backward classes in the Indian judicial system.

SC and ST collectively make up 29.8 per cent of the Indian population as per the latest census. According to data released by the Minister of Law and Justice of India, Arjun Ram Meghwal, High Court judges appointed from 2018 till 02.12.2023 from SC, ST, OBC, and Minority stood at 23, 10, 76, and 36, respectively. Cumulatively, the total appointments from 2018 to 2023 stood at 23 per cent, and per year, the progress is barely 2–5 judge appointments. 2024 saw some progress for Dalit representation in the apex court, with the appointment of Justice Prasanna B Varale. With the elevation of Justice Varale as a Supreme Court judge, the apex court for the first time has three judges belonging to the Scheduled Castes: Justices BR Gavai, CT Ravikumar, and Varale. It must be noted that within each of these communities, we have observed progress and efforts towards representation, but to effectively uplift these communities, their intersectionalities must be acknowledged and worked upon.

Preferred language

A stereotype is essentially an overgeneralised view or belief towards a social community. It may often reflect the deeply rooted image or expectations of them. Stereotypes are formed through the process of social learning and are not the result of just one incident but years of learning through different social environments such as family, peers, and society.

In Indian society, stereotypes regarding women, sexual minorities, and socially backward classes have not failed in their attempt to form hindering norms and societal conventions. These prejudices negatively influence society and often deprive the said communities of basic human treatment, curtailing their rights as citizens.

To address these stereotypes, the Supreme Court of India released a Handbook on Combating Gender Stereotypes which identifies prominent stereotypes against women and sexual minorities and guides through addressing the issue. It also lists down stereotypical terms and phrases used to describe a woman, wife, and person of the LGBT+ community. Some of the common stereotypical terms that the handbook identifies against women, such as “Career woman,” “Chaste woman,” “Fallen woman,” “Seductress” and “Harlot” for the LGBT+ community, such as “Effeminate,” (when used pejoratively) “Faggot,” “Transvestite” were discouraged from being used.

Prejudices are strengthened when the judicial system itself uses daily expressions of gender bias leading to sexual harassment at work for female attorneys and judges. The necessity of the hour is to enforce what has already been established in our Constitution. Handbooks, guidelines, and awareness workshops happen but are not enough to uproot the deeply entrenched stereotypes in society.

Earlier, the saying “Justice is blind” would be used to denote the impartiality with which justice is given; rather, it may have been blind towards the generations of mistreatment. If one might hope, maybe with the unveiling of the new lady justice, actionable steps would be taken to curb the visible hidden hindrances within the system.

About the author(s)

Ketki (she/her), is a curious political science student who loves exploring new ideas, places, and cultures. She has gained diverse work experience across event logistics, exhibitor relations, and research, always eager to learn something new. She has a soft spot for cats. In her free time, she loves to travel, listen to wildly different music and watch thrillers.

Indian laws are biased against men.