From the perspective of secularism and the quest for gender equality, some argue that Islamic personal law, which may include provisions perceived as discriminatory against women, should be reformed or possibly abolished to guarantee equal legal rights for all citizens regardless of religion. However, this remains a deeply complex and contentious issue, with strong arguments on both sides, and the degree to which Islamic personal law should be altered to uphold gender equality continues to spark significant debate.

Muslim personal laws cover issues such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, etc. In confronting unjust treatment, women have often been compelled to challenge the institution of family—frequently their sole support system in society. Achieving equal rights, both legally and culturally, has therefore been a long and arduous struggle.

The controversy over adopting a uniform family law in India has been framed as a clash between advocates of individual rights for Muslim women—portrayed as victims of unjust gender practices within the Muslim community—and defenders of the collective rights of the Muslim minority, often depicted as conservative and patriarchal. The core idea of secularism is that the state should not favour one religion over another, and gender equality means equal rights for all genders.

Secularism and the debate over the Uniform Civil Code in India

In India, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains are governed by Hindu law, whereas Parsis, Christians, and Muslims follow personal laws based on their respective religious texts or interpretations of those texts. In the Indian legal system, laws are applied either based on territorial jurisdiction or religious identity. Personal laws, as we know them today, were established during the British Raj. Women from all communities have, at various times, challenged the injustices within these laws or sought redress through the courts.

During the framing of the Constitution, some of its architects argued that if India were to be a secular state, where governance remains separate from religion and culture, there should be a single uniform law for the entire nation—a concept supported by leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Bhimrao Ambedkar. Article 44 of the Indian Constitution, part of the Directive Principles of State Policy, explicitly states: “The State shall endeavor to secure for the citizens a Uniform Civil Code throughout the territory of India.”

However, being a directive principle, it is not enforceable by law but acts as a guiding principle for governance. Secularism in Indian constitutional law does not rely on the strict separation of religion and state, but the postcolonial Indian state has influenced religion by creating laws that define its boundaries for different religious groups.

Secularism, Islamic law, and gender justice in India

Secularism is not simply the separation of religion and state, as commonly believed, but involves both being intertwined. As Hussein Agrama describes in “Questioning Secularism: Islam, Sovereignty, and the Rule of Law in Modern Egypt” (2012), secularism is a “questioning power.” A secular state, therefore, is always in the process of secularising—this process is never fully complete. Katherine Lemons, in her book “Divorcing Traditions” (2019), refers to the adjudication of Muslim divorce traditions in India as a prime example of this ongoing process of secularism. Laws governing marriage and divorce, matters concerning infants and minors, adoption, wills, intestacy, succession, joint families, and partition are primarily governed by the personal laws of the individuals involved.

In India, Muslims are predominantly Sunnis, largely following the Hanafi school, while Shias mostly adhere to the Ithna Ashari school. Traditional Shari’ah law is rooted in the concept of justice and serves as a comprehensive guide to the life of a Muslim, covering all aspects of law, ethics, and etiquette, from birth to death. These rules have been developed through ijtihad, using sophisticated jurisprudential techniques. The Quran remains the primary source of all Islamic law, as the Word of God. However, in matters not explicitly addressed in the Quran, rules were developed based on the hadith and through consensus. Differences between the schools arose due to varying interpretations of hadith, consensus, and the application of qiyas (analogy).

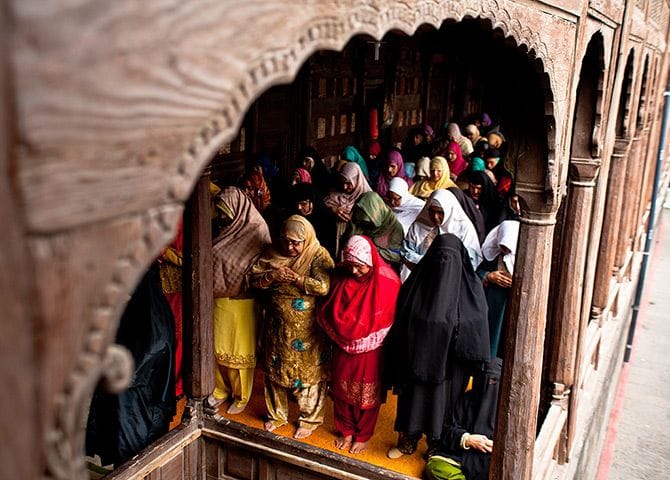

In Delhi, there are four distinct types of adjudication forums: an NGO-run women’s arbitration centre, known as a mahila panchayat; dar ul-qazas, often referred to as “shari‘a courts,” a dar ul-ifta, where authoritative Islamic legal opinions are issued; and a spiritual healing practice. While these institutions are non-state, they are not informal. Each operates with a clear logic and consistent adjudication procedures and outcomes, drawing on the Hanafi school of Islamic legal interpretation, and their normative frameworks integrate diverse historical influences. In dar ul qazas headed by the Qazi, men can secure divorce extra-judicially, whereas women can initiate divorce only judicially. In other forums, women do not fully have the agency to initiate divorce; instead, they must present ‘legitimate‘ or ‘tangible‘ reasons for seeking it.

Speaking of inheritance rights, many Muslim women either were unaware of the inheritance rights granted to them by Shariat, or, even if they were aware, chose to forgo these rights out of fear of damaging family relationships. Often, familial pressure and the fear of upsetting brothers—whom they might need to approach in the event of a divorce—prevent them from claiming their rightful share. The demand for secular, gender-just laws put forward by Muslim women’s groups acknowledges that Muslim women must challenge not only Muslim Personal Law and family dynamics but also the politics of demonising anything associated with Islam.

In 1978, Shah Bano filed a petition seeking maintenance from her husband, a lawyer well-versed in personal laws. In response, he divorced her and refused to pay maintenance beyond the iddat period. The Supreme Court’s 1985 verdict granted her relief, but it sparked protests from conservative Muslims who felt the court had interfered with Shariat law (Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum). In 1983, Shehnaaz Shaikh, who later founded Aawaaz-E-Niswaan, a women’s organisation, petitioned the Supreme Court to challenge several provisions of the Muslim Personal Law of 1937. By 2007, a group of Muslim women activists established the Bhartiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA) to address the challenges faced by Muslim women. A key objective of the BMMA was the codification of the Muslim Personal Law to eliminate unjust practices carried out in the name of Islam (BMMA Report on Muslim Women’s Rights, 2011).

Gender roles, and the tensions of equality

Secularism is often regarded as a cornerstone of liberal democratic governance, ensuring the separation of religion and politics. This separation allows individuals to freely practice their faith without coercion or state interference, as enshrined in the right to religious freedom. Despite the surge in projects and scholarship on secularism over the past decade, there remains a notable gap in understanding the central role that gender plays in debates and contestations surrounding the secular.

Polygamy and talaq within Sharia systems violate both secularism and equality; secularism is undermined because the Muslim community is treated differently, while equality is breached because Muslim women are treated unequally. Both secularism and equality are invoked to portray the Muslim woman as weak, subordinate, and victimised—while simultaneously promoting a homogenising agenda driven by Hindu majoritarianism and male supremacy. The demand for and opposition to family law are ultimately framed as a conflict between the secular liberal principle of individual equality and the principle of multicultural religious pluralism. This framing highlights a central debate in liberal political theory about how to balance the rights of minority groups within the broader society with the rights of individuals within those minority groups.