Dalit feminism is an emergent movement out of the larger movement for Dalit assertion. For the longest time, Dalit women have been perceived as absent from the movement and from the literature of the Dalits. In the early history of the Dalit movement in the 1930s, autonomous Dalit women’s organisations protested against practices like child marriage, enforced widowhood, and dowry. But increasingly, women’s involvement in the Dalit movement has been overshadowed by the dominant power structures of the society of the time.

Sociologist and feminist scholar Sharmila Rege in her essay “Dalit Women Talk Differently,” mentions in a section about the “Masculinisation of Dalithood and the Savarnisation of Womanhood” during the Dalit Panthers movement in Maharashtra in the 1970s, highlighting the systemic marginalisation of Dalit women’s voices.

Nevertheless, Dalit women’s writing has opened perspectives and interpretations of Dalit experience from the intersection of caste and gender and reveals how Dalit women are doubly oppressed by Brahmanism and patriarchy. Dalit women’s writing has strengthened not only the larger Dalit movement but has also redefined our understanding of feminism in general by including the voices as well as the political standpoint of marginalised groups of women.

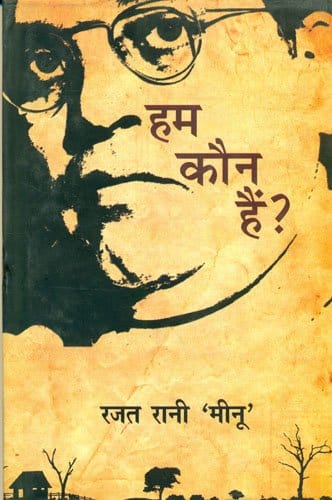

Rajat Rani Meenu, a prolific Dalit writer

Rajat Rani Meenu is a prolific Dalit writer, critic, and professor. She was born in a village named Jaurabhud in the Shahjahanpur district of Uttar Pradesh. Her works are mainly centred around the intersectionality of caste and gender, giving a newfound voice to Dalit feminism.

Two of her short stories in particular, namely “Darr” and “Sunita,” depict the two contrasting consequences of caste oppression, the former being a tale of looming fear and submitting to caste hierarchy, the latter being a tale championing Dalit consciousness and freedom. “Darr,” was published in the July 2024 edition of the Hans magazine, a magazine pioneered by Rajendra Yadav, who is a big name in Hindi Sahitya and Dalit print culture. The other story named “Sunita,” which is Rajat Rani’s first ever published story, is taken from her short story collection titled “Hum Kaun Hain.”

‘Darr‘ and internalisation of caste politics/casteism

The narrative chronicles the everyday happenings in the home of a prosperous married couple. The conflict arises when one day the wife asks the husband to hire a domestic worker as she’s unable to manage the household chores on her own. The husband, Kuldeep, upon hearing the word “Baai” (which means domestic worker), is troubled by flashbacks of his mother working as a maid for the upper caste people, and who, upon endless requests by her son to drive her from poverty, would refuse him. The story is based on this refusal, which stems out of a deep-seated and internalised fear to bridge caste and class differences. It very aptly presents the psychological phenomenon of a self-fulfilling prophecy in the character of the mother.

The mother is repulsed by the job prospects of her son. She finds it hard to believe that her son has actually made progress in his social mobility. Her parental generation and that of her in-laws had never once seen the forbidden light of the alphabet. However, inspired by Ambedkar’s ideals, she made it her mission to break down caste barriers by educating her son, even if it meant sacrificing her own well-being.

Kuldeep’s mother is gripped with this threat of caste atrocities that her poverty-stricken condition makes her develop an enmity and repulsiveness towards the people of the locality, particularly the upper castes. This is clearly evident from the instance in the story when Kuldeep visits her mother after a very long time and hears from her mother about her fear and concern for his safety when the news spread across the locality that he’d secured a huge, high-paying job in the city. The fear had such a hold on the mother’s psyche that she vehemently refused a journalist’s offer to have both hers and her son’s photograph in the newspaper.

Kuldeep’s mother also feared losing her job as a cleaner/sweeper at the houses of upper castes as a result of the news being spread and the underlying truth of them being ‘untouchables.’

In order to protect her son from her own poverty, the mother repeatedly denies her helpless condition and remains indifferent to her son’s pleas.

Rampant casteism in the workplace/environment

The boss of the office at which Kuldeep works manipulates him by offering him a large sum of money, around twenty to twenty-five lakhs, in the guise of financial support when, in actuality, he can’t stand seeing Dalits rising to positions of power and wanted him to leave the job as quickly as possible.

A peculiar instance of casteism in the case of Kuldeep’s mother is evident from the character of ‘Ramratiya Chachi‘ who very much lives in a similar socio-economic condition as Kuldeep’s mother, in a hut, but displays a condescending attitude toward her when Kuldeep’s mother asks for some wood and a utensil from her to make tea for her son. Ramratiya Chachi hints in her mockery at the long-standing practice of upper caste people bestowing leftover food, or ‘Joothan‘ to the lowered castes, which has long been viewed by them not as a discriminatory practice but as a noble deed.

Double oppression and poverty/deprivation

The mother works as a domestic worker for upper-caste working women and also manages the household chores of the one-room hut since she had lost her husband to death.

Kuldeep traverses the murky lanes of the painful memories of his mother’s struggle, who had slaved away her life in the housework of working upper caste women but was herself never looked at as a working woman in a caste-ridden society.

Kuldeep experiences the wounds of her mother’s past through his memory. She had struggled her whole life to make ends meet. At any given time, the basic needs of food and clothing were not met together, with one of the two always lacking. This poverty had seeped into the domain of education as well. Kuldeep retraced to his childhood when he wore torn shoes and, apart from textbooks, couldn’t afford all the basic stationery and notebooks.

Fear of breaking the caste mold

Caste identity is so inseparable from the mother’s self that the meagre amount of money she earns by working houses of upper caste women, she can’t let it be snatched from her. The mother, because of her abysmal poverty and because she’s an erstwhile untouchable, is gripped with a fear that the upper caste people might kill her son if they spot him with his mother. The mother herself fulfils the casteist prophecy by alienating her well-off son from her, refusing to leave her poverty-stricken condition, just to protect her son from the overwhelming shadow of caste politics.

‘Casteist prophecy‘ refers to the internalised fear of caste atrocities to the extent that this fear turns into a self-fulfilling prophecy. The victim ( in this case Kuldeep’s mother) deliberately acts according to the perpetrators’ (upper caste) whims and wilfully submits to the caste hierarchy and symbology.

“Sunita” and the marriage as the conduit for casteism and patriarchy

This story begins with the seven-year-old Sunita having developed the consciousness of being a ‘girl‘ and learning about the destiny that awaits her.

In the very beginning of the story, Sunita’s father gets outraged at her desire for higher studies, telling her to stop at basic literacy itself, as anyway she’ll not become a collector, officer, or public official, nor does she possess the capability to become them. According to her father, she’ll get married, and it’s her brothers who will carry the lineage forward. It was then that Sunita had the biggest realisation that she’s a ‘girl‘ and that marriage is her supposed destiny, and this shook her and made her even more determined to study further.

Reinforcing caste prejudices

Sunita’s parents supported her education only as a pretence. Her father acted indifferent to her academic achievements. It was both financially as well as societally burdensome for them to spend on her education. This is because the local goons and upper caste boys used to tease and mock her on the streets by stating ironically that “even the upper caste men don’t allow their daughters to study much, but here the daughter of a Chamar dares to become an officer.”

Then, there’s the village head named Sajjan Singh, who one day mockingly advised Sunita’s father to halt her studies and get her married off as soon as possible.

Led by patriarchal conditioning and Sanskritisation, Sunita’s father desperately tries to marry off her fifteen-year-old daughter to a rich 50-year-old man. But even Sunita’s mother vehemently refuses to accept this decision. Sunita then makes a plea to her mother about her higher studies and stresses the importance of education for Dalits in order to break out of the cycle of caste oppression. She explains to her mother why the Chamars and the Bhangis are divorced from education because the Brahmanical order wants them to continue the generational drudgery of cleaning and leatherwork, thereby perpetuating the vicious cycle of casteism.

Dalit consciousness and the importance of education

It’s here in the narrative that Sunita witnesses the birth of Dalit consciousness within her, which is further nurtured by her extensive reading of Ambedkar. She pursues her BA, BEd, but when she applies for a teaching position in semi-government colleges in UP, she witnesses blatant caste discrimination, where people of lesser capabilities were being accepted for the position just on the basis of caste. So, then Sunita moves to Delhi and finds a job in RK Puram. But her zeal for academic brilliance never took a backseat. She continued with academics and completed her MA as well as LLB. She was even determined to be an IAS officer.

But Sunita’s life trajectory took a dramatic turn when she gave a highly moving speech on a public platform about the upliftment of the two social groups: women and Dalits. She expressed her resentment for Dalits being called “Harijans” and for Gandhiji for naming them so. Sunita held Babasaheb Ambedkar in higher regard as compared to Gandhi, who never wanted the upliftment of Dalits and women. She was disgusted with the term Harijan, as it had become like a cuss word for the Dalits and was entirely unconstitutional, merely serving as token representation, reinforcing untouchability.

Following this political speech, we see Sunita aspiring to become a member of parliament. And indeed she does become an MP. Towards the end of the story, we see Sunita as a successful woman confronting her father, whose egotism and conservatism are crushed, and who finally learns that “daughters too can prove to be mentors to their father.”

Ambedkar’s influence on Dalit literature

There’s also this looming presence of Dr. BR Ambedkar in the narrative. His words and ideals are peppered throughout the narrative, emphasising socialism, equality, and women’s education. In the story, Sunita recalls Ambedkar saying, “Without women’s education, Dalit revolt against Brahmanism would prove to be fruitless.” Ambedkar’s emphasis on education as a tool for rising above socio-economic backwardness is what binds both the narratives of “Darr” and “Sunita,” giving it the symbol of a protest against the dying of the light.