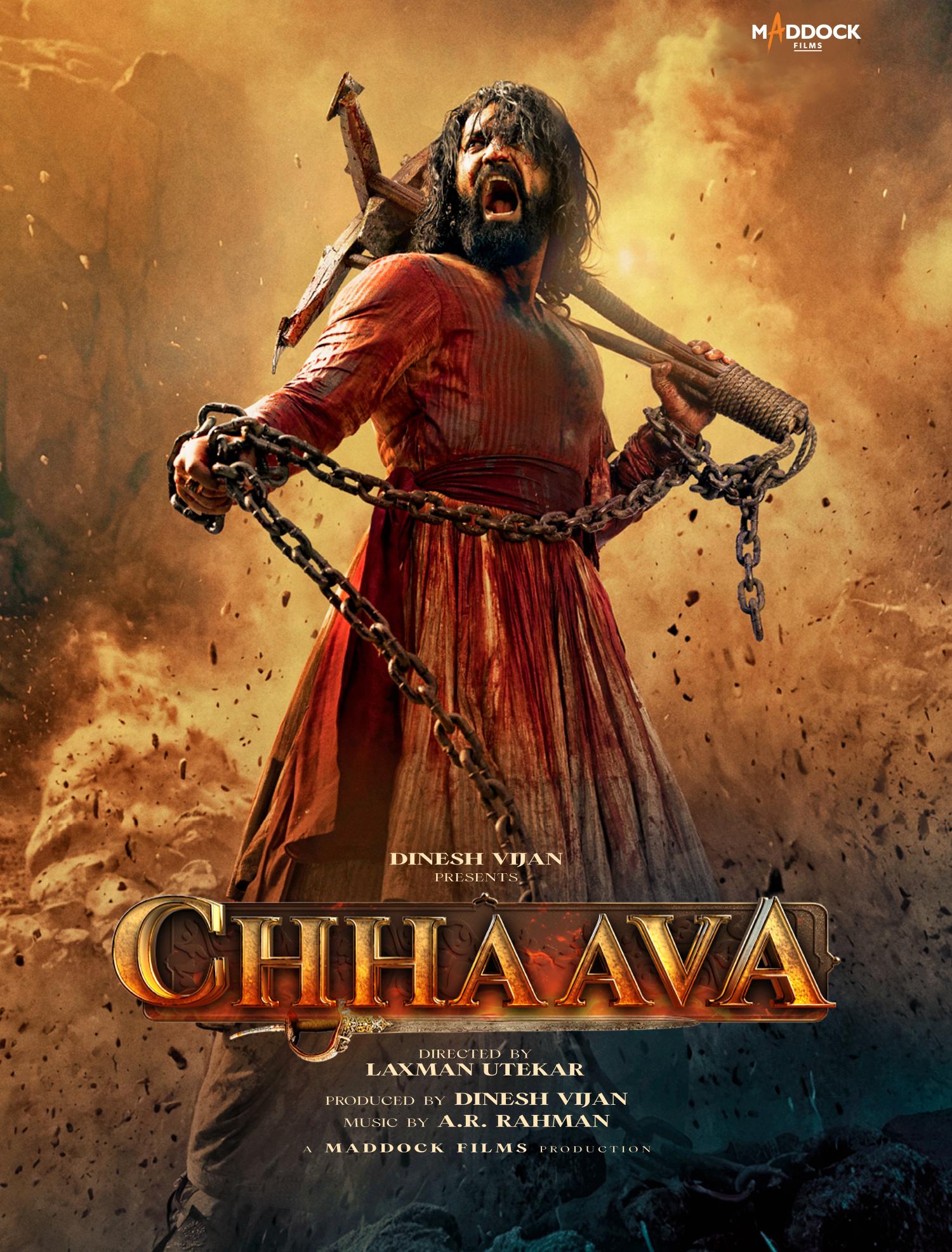

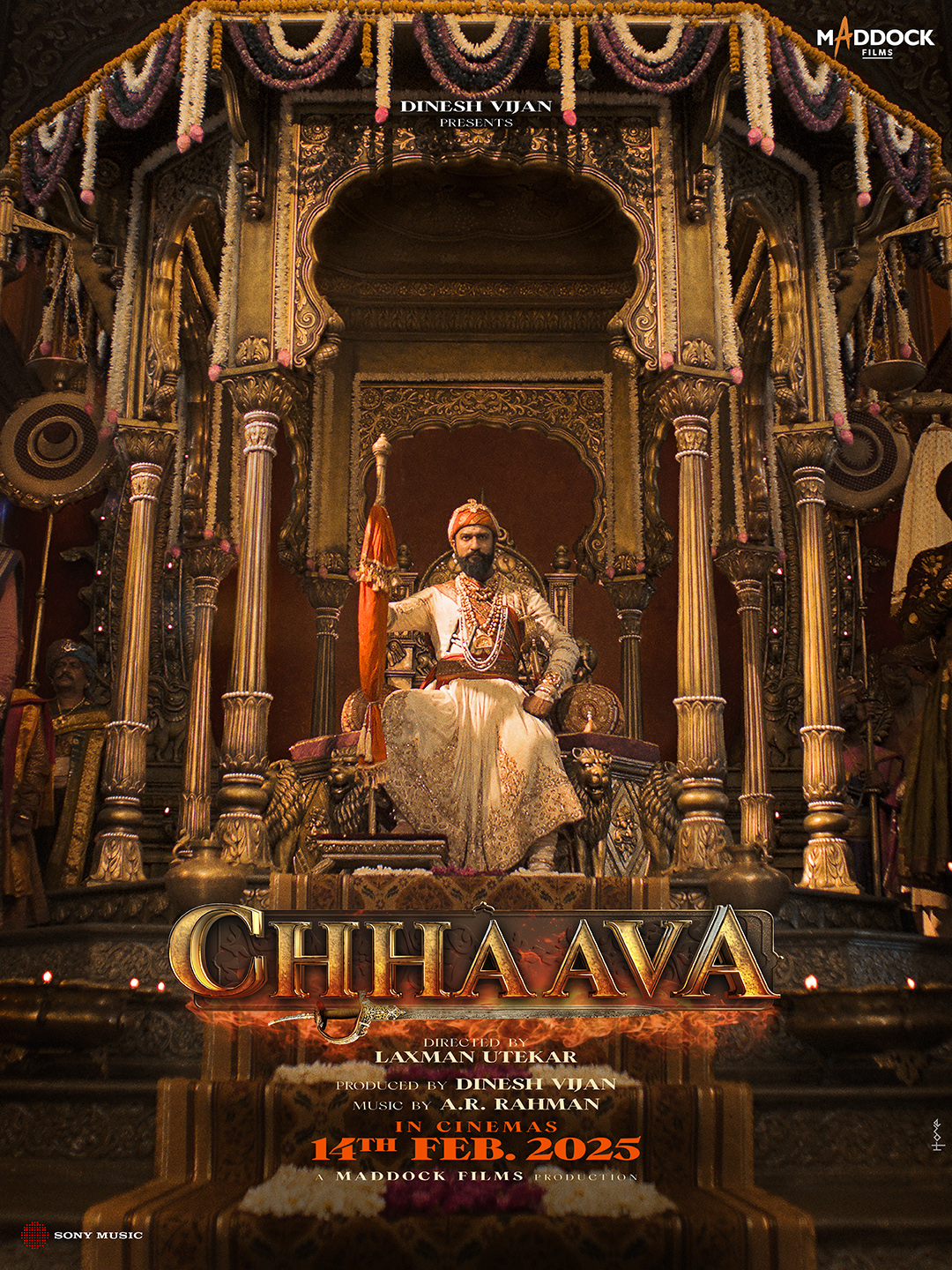

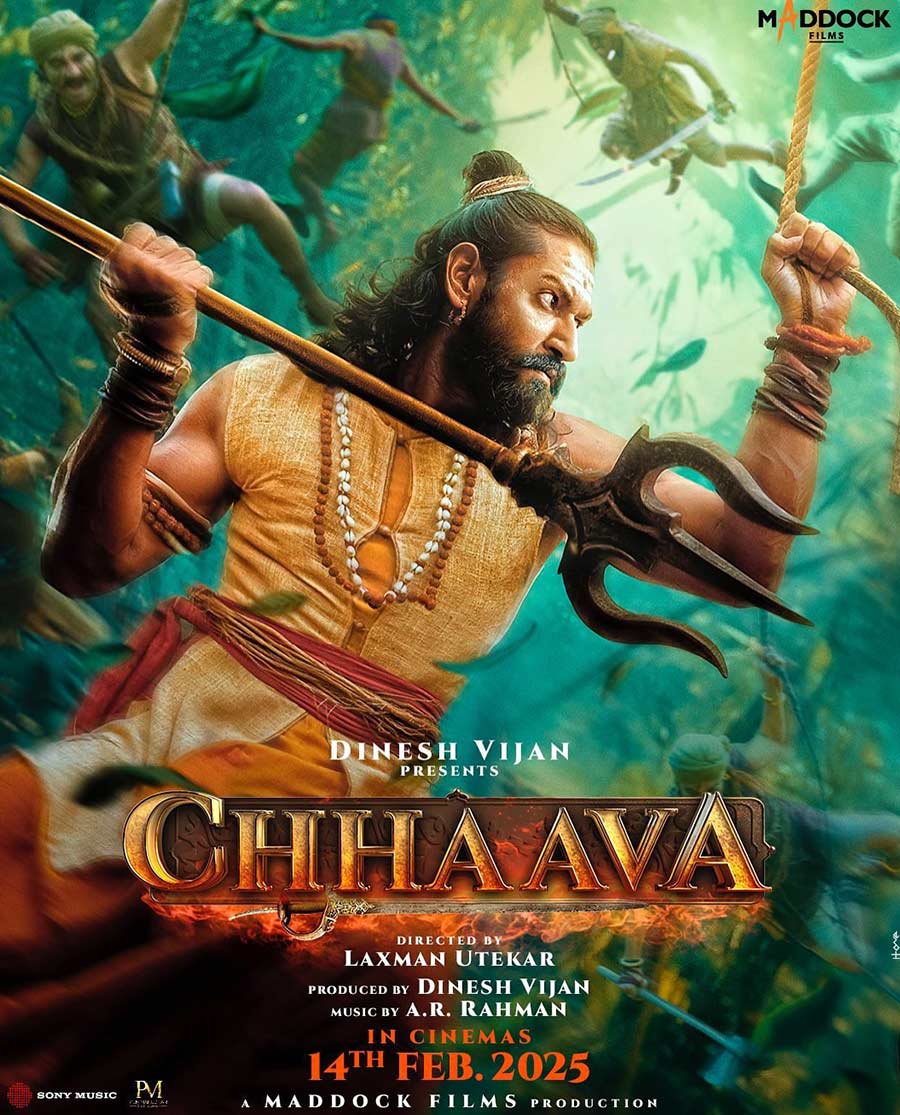

Chhaava, meaning lion’s cub, is also the name of the book written by Shivaji Sawant- which writer-director Lakshman Utekar used as a source of inspiration. As an obligatory justice, Lakshman showed Vicky Kaushal who played the titular role of ‘Chhatrapati’ Sambhaji Maharaj as a fearless fierce warrior.

He is the eldest son of ‘Chhatrapati’ Shivaji Maharaj– the founder of Maratha empire. But, at the end, we are left with an imbalance of something lacking.

He is the eldest son of ‘Chhatrapati’ Shivaji Maharaj– the founder of Maratha empire. But, at the end, we are left with an imbalance of something lacking. Chhaava covers almost 8-10 years of time period. But its entire energy is focused on nothing but the destruction of Aurangazeb (the film calls him Aurang for some reasons, played mutely by Akshay Khanna).

Vicky Kaushal: like a Chhaava

Vicky Kaushal is one of those actors who does author-backed roles once, yet balances the routine character tropes. In recent times, films like Govinda Naam Mera, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, The Great Indian Family, Bad Newz are compensated with solid author-backed roles like Sardar Udham, Sam Bahadur, and now Chhaava. The balance is quite right and the effort seems to have only doubled.

You can really feel the volume of his punch when he punches. The fierce facial expression doesn’t fade away anywhere in the film. The actor’s will to deliver top-notch performance equalling the legacy of Sambhaji Maharaj is very well evident. But, all the focus of the story is on Sambhaji.

No other character gets a breathable space. Especially, Ashutosh Rana (who played the role of Hambirao Mohite) and Rashmika Mandanna (who played the role of Sambhaji’s wife, Yesubai) got very minimal screen-value despite the characters having the emotional strength to compensate the overall violence of Chhaava. So, the narrative of only destroying the kingdom of Aurang makes Chhaava an impactless loud dud.

A loud dud

On one hand, the internet is praising Jayadevan Chakkadath’s sound design for Mammootty’s Brahmayugam. On the other hand, the loud noise is being equated with great music. KGF, Salaar, Kanguva are a few recent examples of films with loud scores. However, both Kanguva and Chhaava faced a bit of backlash for its over-the-top loud music. The background score of Chhaava gets diluted in the loaded loud fights, except Rahman’s vocals bringing the music alive with ‘Aaya re Toofan‘ and the melodious track of ‘Jaane Tu‘.

The background score of Chhaava gets diluted in the loaded loud fights, except Rahman’s vocals bringing the music alive with’Aaya re Toofan‘ and the melodious track of’Jaane Tu‘.

The fights directed by Parvez Shaikh and Todor Lazaroy deserve a special mention. The fights are well placed and follow all the standards of a modern epic war fight. The pre-climax fight scene where Sambhaji fights every soldier single handedly, makes the one-sided battlefield into a bloodfield. This fight scene runs long and becomes the anchoring event for the upcoming climax which is unlike any film that glorifies valour.

The undisguised jingoism of Chhaava

It is no longer a surprise to know that the trend of filmmakers making films on the themes of mythology and history is to (also) serve the current popular political belief system which is an ultra-nationalism that takes pride in the Hindu religion.

The hero, Sambhaji, saves the Muslim child from the war zone to give him to the mother. We also see the villainous Mughals burning a shepherdess alive. The messaging becomes clear and blatant.

The jingoism of Chhaava becomes even more evident when you observe the overall arc of the film. In its series of court-house dialogues, Sambhaji says that he wants every common citizen to walk in the streets with pride like a king. Yet, we don’t ever see a civilian in the film. All the coterie conversations are about stopping the spread of cruel Aurang, and nothing else.

In its series of court-house dialogues, Sambhaji says that he wants every common citizen to walk in the streets with pride like a king. Yet, we don’t ever see a civilian in the film.

In the climax, before Aurang’s daughter’s orders to cut off Sambhaji tongue, Aurang asks him to give up to stay alive but on one condition: he has to change his religion to Islam, to which Sambhaji replies, ‘Come and join the Marathas and you don’t even have to change your religion.’ The audience in the theatre cheered and whistled and clapped. The nexus between the politics of cinema and contemporary politics made itself clear.

Chhaava once again reinforces the skepticism of Bollywood that is currently trying to ride the political wave even when it is expected, at worst, just to flow with it.

Thus, Chhaava remained an impactless loud dud. It is an example of agenda-led filmmaking that focuses more on villainising the enemy (Mughals) than to humanise the hero (Marathas).

Chhaava is currently playing in theatres.

About the author(s)

Azdhan (He/Him) is a full-time film critic freelancing for Feminism In India. If he is not reading or writing, he will just be zoning-out– even if there is no window– always thinking of writing his next novel to adapt it into a screenplay. The backend process of trying to build something that can solve urban loneliness is also always on his mind.