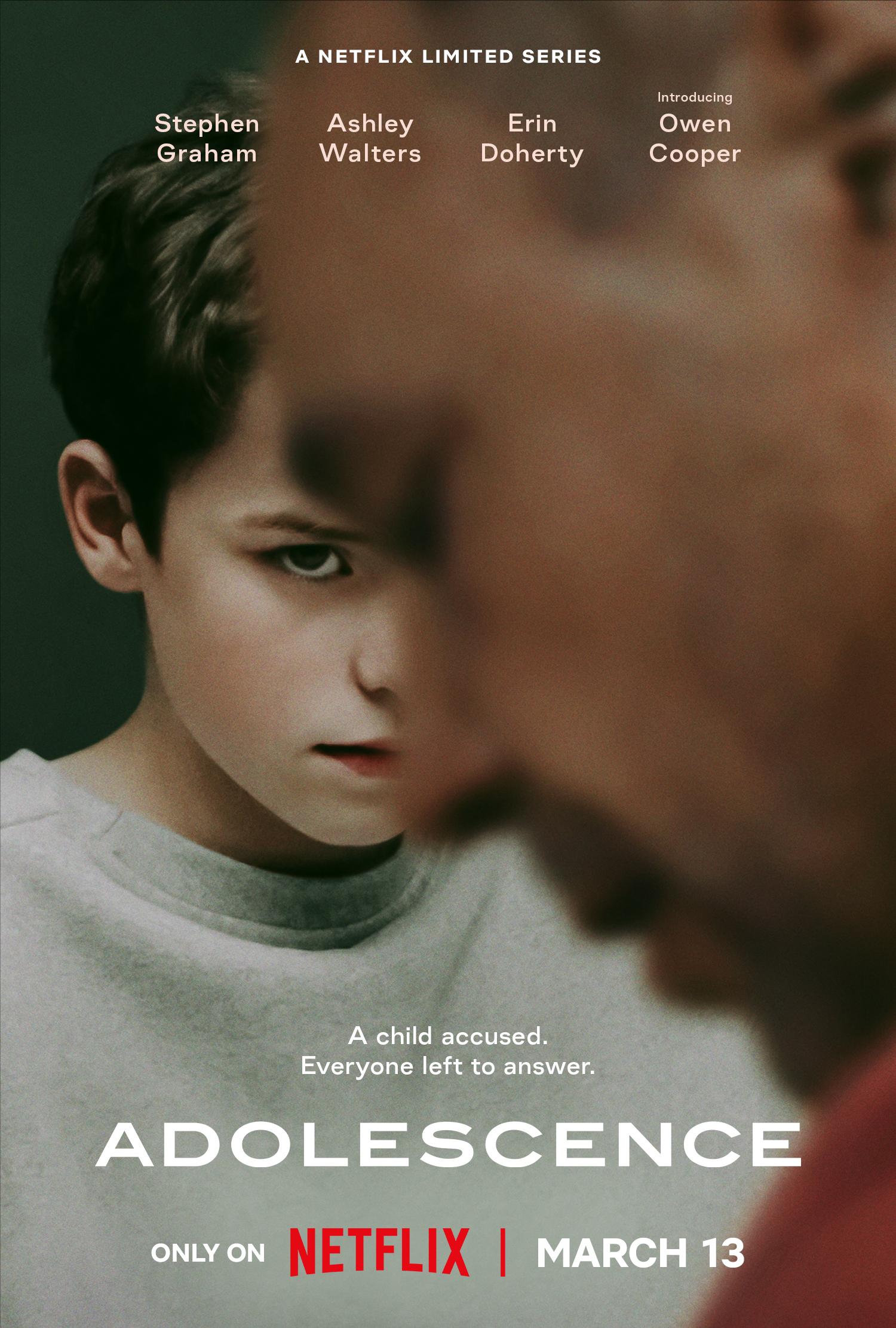

‘I’m only 13.’ This simple truth lies at the core of Adolescence, Netflix’s gripping new drama from Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham. A harrowing and meticulously crafted four-part series, shot in one single uninterrupted take, Adolescence shows how a vulnerable, self-loathing, ordinary school boy can be radicalised without anyone noticing, revealing how these toxic forces are often ignored or misunderstood.

A harrowing and meticulously crafted four-part series, shot in one single uninterrupted take, Adolescence shows how a vulnerable, self-loathing, ordinary school boy can be radicalised without anyone noticing, revealing how these toxic forces are often ignored or misunderstood.

Emotionally layered and socially incisive, Adolescence not only tells a compelling story but doubles up as a profound commentary on societal issues.

The show will resonate with troubled teens, unsettle their parents, and the devastating questions it raises will linger long after the credits roll. The narrative circles the central question: How did Jamie get here? It follows the Miller family, whose world unravels when 13-year-old Jamie is arrested for the murder of his classmate, Katie. It immerses us in a teenage world dominated by the internet, —an environment that adults, despite their best efforts, struggle to understand or control.

Adolescence is about more than just a murder. It’s a sobering reflection on modern masculinity, shaped by technology and steeped in male rage. It paints a stark picture of the corrosive influence of misogyny, while also grappling with the deep-rooted fear and societal pressure surrounding rejection. The series pulls no punches in its exploration of these uncomfortable truths, offering an eye-opening, gut-wrenching look at the realities of adolescence in the digital age.

With its masterful blend of artistic brilliance, dazzling performances and raw emotional intensity, Adolescence is a cry of despair and a call to action.

It forces us to confront: what are we teaching our young boys, and how do we expect them to navigate a world that feels increasingly toxic when our concept of masculinity still seems to depend on boys and men doing so alone.

A journey from boyhood to manhood in Adolescence

The story comes to life through small, telling details, such as Jamie’s space-themed wallpaper and the moment when he wets his pants as armed police burst in—moments that expose the vulnerable, innocent boy behind the shocking violence.

Remarks like ‘Do you like me?‘ by Jamie in Episode 3 of Adolescence and ‘Were you popular with girls and stuff?‘ by Ryan in Episode 2 reveal how these boys measure their self-worth, fixated on shallow markers of masculinity and social status.

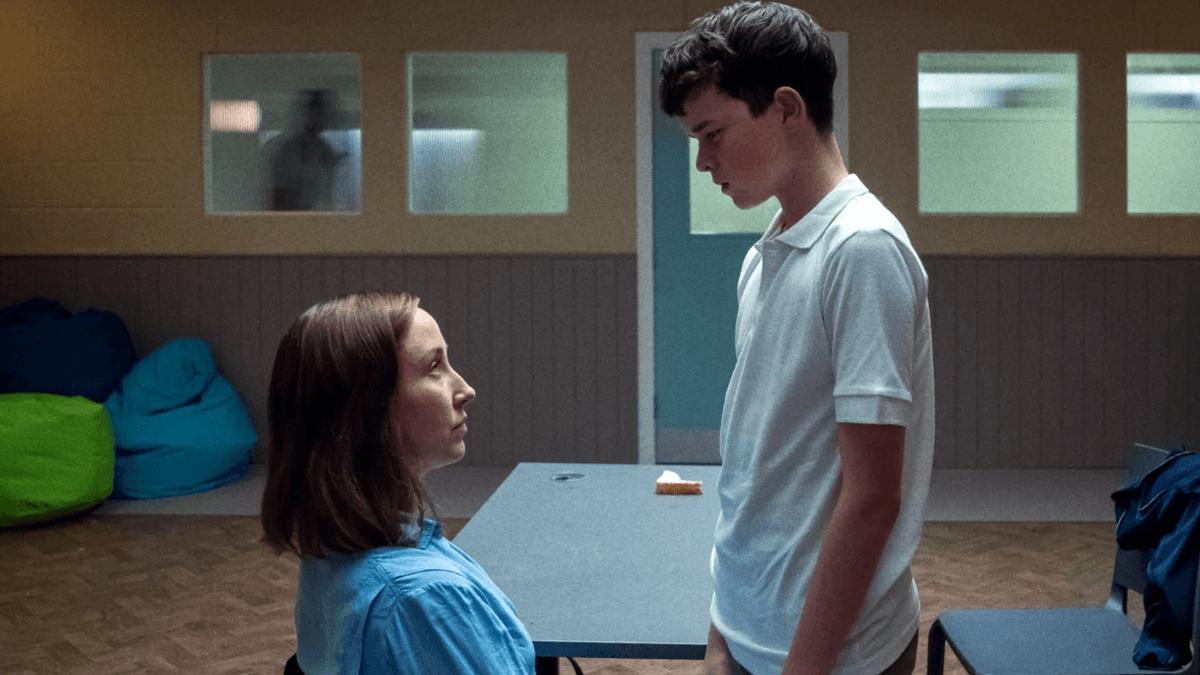

In Episode 3 of Adolescence, Jamie’s transformation from sympathetic to menacing is palpable, shifting from a lost child to an angry young man in just a few moments.

In Episode 3 of Adolescence, Jamie’s transformation from sympathetic to menacing is palpable, shifting from a lost child to an angry young man in just a few moments.

During a session with his psychologist, Jamie’s frustration boils over. He confronts her angrily, shouting, ‘What a shame, you’re scared of me,‘ while defiantly disregarding her instructions. In another chilling moment, Jamie remarks, ‘I could do anything with her body, but I did not,’ revealing a disturbing objectification of women and a twisted understanding of power and control.

Later in the same episode, Jamie admits that he asked Katie out only because he perceived her vulnerability, believing she might say yes. This reflects his distorted view on relationships and gender dynamics.

In the final act of the episode, he asks his psychologist if she likes him. When she refuses to answer, he lashes out, banging on the windows. The boy who once wet himself in fear now channels his pent-up anger into violent behavior.

These scenes raise a crucial question: what does the life of a young boy look like today, when everything is available to them at the click of a button? What role models exist to help them navigate this confusing world?

In Adolescence, Jamie, a vulnerable child, absorbs harmful ideas from the internet that validate his feelings of isolation and alienation. Lacking the emotional filters to discern right from wrong, he internalises these beliefs, fueling his sense of entitlement.

Lacking the emotional filters to discern right from wrong, he internalises these beliefs, fueling his sense of entitlement.

This is where the toxic world of “incel” culture starts to take shape. The messages young boys and men receive about what they are entitled to from women begin to take root, revealing a deeper danger.

Tech addled masculinity in Adolescence

The term “incel,” short for “involuntary celibate,” originally referred to individuals, usually men, frustrated by their lack of sexual experiences. It was coined in 1997 by Alana, a woman from Toronto, who created a website, Alana’s Celibacy Project, to support people struggling with romantic relationships. Over time, however, the term has morphed into a toxic online subculture marked by hatred, violence, and a deep mistrust of women, with many members blaming the feminist movement for their plight.

A 2022 study in Current Psychiatry Reports identifies key ideologies that unite the incel community: a focus on appearance-based hierarchies where physical looks dictate sexual success and social value; the belief in “female hypergamy,” or the idea that women exploit their sexuality to climb the social ladder at men’s expense.

Many incels discuss reversing gender equality, often suggesting coercion or rape. The term “incel” has been tragically linked to violent acts against women, most notably with figures like Elliot Rodger, the University of California student who killed six people and injured fourteen others before taking his own life. Rodger was a self-described incel and became a figurehead within the community. Likewise, Jake Davison, who killed five people, including his mother, in Plymouth, was also an incel.

Clusters of online spaces where men mobilise against feminism construct the ‘manosphere’ – these online spaces promote toxic masculinity, misogyny, and opposition to feminism—has expanded beyond obscure forums like Reddit and 4chan and into mainstream social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok.

Among the most influential figures in this space is Andrew Tate, a British-American influencer who gained significant attention for his virulent misogyny. Tate’s message, echoed by other figures like Jordan Peterson and Hamza Ahmed, promotes the rejection of feminist values, asserting that the key to success is to embrace traditional gender roles and male dominance.

In the manosphere, “red-pilling” is a term borrowed from The Matrix (1999), where the protagonist chooses between the blue pill (the status quo) and the red pill (the “truth”). To be “red-pilled” means believing men have awakened to the “real world”—a world where women are shallow, focused on traditional masculinity, and manipulative. This ideology feeds into the growing narrative of male entitlement prevalent in the manosphere.

The issue isn’t just the existence of this culture, but the deeping chasm between adults and the forces shaping these boys.

In episode two of Adolescence, a revealing exchange between the investigating officer and his son highlights this generational divide. When Adam tells his father that Katie called Jamie an incel on Instagram, the officer, clearly baffled, responds, ‘Who isn’t an ‘involuntary celibate’ at 13?‘

When Adam tells his father that Katie called Jamie an incel on Instagram, the officer, clearly baffled, responds, ‘Who isn’t an ‘involuntary celibate’ at 13?‘

With a hint of frustration, Adam remarks, ‘It’s just embarrassing how you blunder about it.’ and decides to give a mini crash course of his world, underscoring how out of touch adults are with the online culture and the intense pressures young people face today.

The real issue lies in adults’ failure to recognise the signs of distress and provide the necessary guidance to help these boys navigate the complexities of adolescence in a hyper-connected, often dangerous world.

Many parents are themselves emotionally underdeveloped, unable to provide the support and role modeling their children need. Instead of offering positive examples of how to navigate life as a man, these children are left to consume harmful, unchecked narratives online, often without the presence of an adult who can counteract or challenge these damaging views.

The power of algorithms

Back in the day, families would gather together in their living rooms to consume films, news, and mainstream media. However, with the rise of the internet, that shared space has fractured, leading to a sense of isolation. Children now consume content alone, in their rooms, on their phones. And the algorithms of platforms like TikTok and Instagram target their vulnerabilities, feeding them content that plays on their loneliness, insecurities, and feelings of lack of control. These platforms gamify harmful content, and over time, harmful views and ideologies begin to normalise.

In the final episode of Adolescence, while reflecting on Jamie’s behavior, his father says to his mother, ‘We thought he was safe in his room. What harm could he do there?‘

There is often a stark gap between parents’ idealised perception of their children’s online lives and the reality of what they’re actually engaging with. The issues of discrimination, misogyny, and homophobia that exist within society are only amplified online. What’s happening is that these online ideologies are moving from the screen into real-life spaces, like schoolyards, where they impact young people’s offline behavior. Parents may think their children are safe in their rooms, but without awareness of the dangers lurking on their phones and laptops, they’re unaware of what their children are actually consuming.

This disconnect is dangerous. In a world where freedom of speech is often used to justify harmful ideologies, young people, still developing their sense of self, are deeply influenced by what they encounter online. Vulnerable individuals may internalise these views, impacting their self-perception and worldview.

While a bruised ego can be shrugged off in the offline world, online, the damage can be longer-lasting, fostering insecurity and brittleness. It’s no wonder there’s a booming market for self-help content where influencers promise young men status, approval, and validation. Yet this space also serves as a breeding ground for manipulating grievances, feeding anger and resentment, and further entrenching harmful ideologies.

Yet this space also serves as a breeding ground for manipulating grievances, feeding anger and resentment, and further entrenching harmful ideologies.

Enter figures like Andrew Tate, who capitalise on these insecurities, offering promises of status, female attention, and a target for resentment. The appeal is strong, especially for young people seeking meaning and belonging. In a world where so much feels uncertain and out of control, the allure of a simple path to power and validation is irresistible. This is why many young men fall prey to the radicalising influence of the online world, and why the cycle of hate and violence continues to escalate.

Redefining communities

But who is accountable for raising young boys?

In an interview, the writer of Adolescence, Stephen Graham—who also plays Jamie’s father, Eddie Miller—recalls the popular saying, “It takes a village to raise a child.”

This means that everyone—governments, schools, parents, and online communities—needs to come together to provide young men with safer spaces to grow into healthy adulthood. By opening up these conversations and building supportive communities, we can prevent them from sinking deeper into the digital rabbit hole and help them build a healthier future.

We need to establish both online and offline spaces where young men can come together to discuss their feelings, struggles, and the pressures they face. These spaces should foster dialogue, learning, and personal growth, where masculinity is not about rage or suppressing other genders, but about building self-respect and respect for others.

Parents, educators, and communities must take responsibility, providing guidance and support to help young boys become emotionally intelligent, respectful, and empathetic men. It’s about listening to them, engaging with them, and offering alternatives to the harmful ideologies they encounter online.

About the author(s)

Vanita is a lawyer by training and writes stories at the intersection of business & public policy, law, regulations and building inclusive workplaces. She is a Staff Writer for The Ken.