“I did not want to be your mother. I wanted you to know that I was as helpless as you.” It is yet to be well-established that motherhood is a state of existence that goes beyond the biological duties it entails pertaining to the female body. The care, nurture, and constant attention that the child requires from its mother often remain a persistent need going well beyond the infantile years. Indeed, motherhood takes the form of a vocation, a full-time responsibility which is ‘owed,’ to a child, to the point of erasing a woman’s personal identity. Mothers being duty-bound have, throughout history, remained as self-sacrificial beings and, in that regard, had to give up the pursuit of their dreams, remaining confined to the demands of the domestic.

Ingmar Bergman’s 1978 film, “Autumn Sonata” transcends cultural boundaries and even time for that matter, introducing to us the character of Charlotte, who challenges the deeply rooted belief that maternal instinct is a trait inherent in all women. She defies the traditional, self-sacrificial approach to motherhood, choosing instead to prioritise her own autonomy over the demands of maternal duty.

Charlotte’s non-committal approach to being a mother

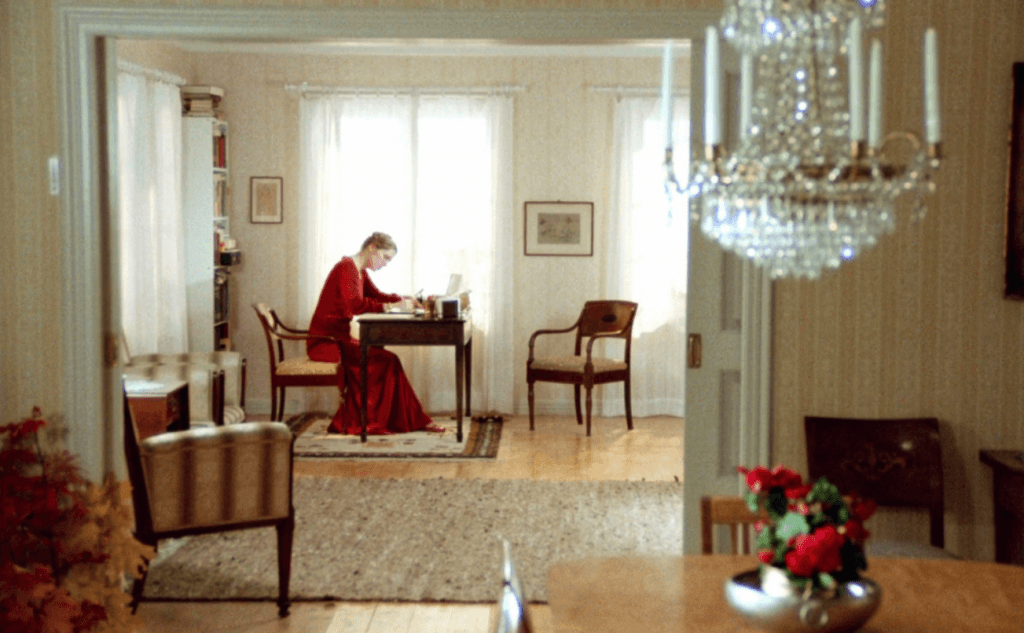

Despite having a husband and two daughters, Charlotte lived a life of her own and occupied a complete existence, which is an unpopular image given the almost impossible task of viewing a woman not in relation to being someone’s wife or mother. She has had a very successful career, in the pursuit of which she chose to not devote her time to her daughters, while also being indifferent to her husband. In looking out for herself, in not being self-sacrificing, she is ridden with guilt for not being able to stay at home.

At the same time, she mentions that every time she came back home, she realised it was something else she wanted. Time and again she has been known to escape from life at home, and in the end, too, she follows that path. We find ourselves asking why she chose to have children at all if she was so determined to keep them away from her life.

As a woman, Charlotte only half meets the expectations. Any non-conformant individual, such as a mother who fails to look after the upbringing of her children, is seen as an outlier within long-established structures where the idea of the heteronormative family remains a dominant one. While she stuck to what her biological identity demanded, she evidently abandoned the responsibilities that came with it, finding herself not enjoying that aspect of her life. What she truly does love is playing the piano, and in the public eye, she has made a name for herself. You win some, you lose some – you can’t have it all. She was not only too preoccupied with the musings of her career; she was also physically absent to know of anything in her family.

As her daughter, Eva’s comment about Charlotte wanting “special exceptions” to be made for her indirectly points to the strictly gendered roles in a patriarchal society one must comply with. The upbringing of a child relies heavily on both parents and in this respect, Eva does not say much about her father, possibly due to his being a ‘victim,’ of Charlotte’s choices, much like her.

The transference of damage and two sides of resentment and hatred

“I don’t know what was worse – you playing at being a wife and a mother or you being on tour.” Eva’s hatred towards her mother stems from the two sides of the same coin – her being an absent figure and the brief presence which brought about her availability. As an adult, she goes through the same set of emotions she did as a child when her mother’s absence would fill her with grief and any news of her return made her restless with excitement. Yet her physical presence proved to be even worse, Eva realising it was no better than last time, as she remained mentally disconnected from the family. Eva remarks that the mother inflicts her injuries upon her daughter “as if the umbilical cord had never been cut.” All Charlotte remembers of the deliveries of her daughters is that they were painful. She expresses no joy at the memory as mothers usually do. After an incident where Charlotte was belittled for not living “a respectable life” at home, she returns to be a “real” family.

Despite defying all norms, she gives in to the internalised belief that without a mother, a family is incomplete. Her consequent dissatisfaction with life at home was taken out as reprimands upon Eva, and she inflicted a considerable amount of damage onto her. Going as far as to make her daughter go through an abortion, the entitlement of imposing her choices upon her daughter is directly associated with being a mother to her.

Whatever damage Eva received is thrown back to her mother, making her acutely aware of the “wrongs” she had committed against her, casting her as a selfish figure for not meeting expectations as a mother. It only made sense that Charlotte escaped home, and they remain separated. That ensured her own happiness, and her daughters, too, were free from the burden of their mother’s “pent-up energy” as Eva put it. She and Helena grew up with a stranger as their mother, reading letters of the adventures that lay beyond their world. Ultimately, Eva sticks to life at home, a place where Charlotte cannot imagine herself to be – coming down, simply, to what one chose.

Eva’s inability to see herself as a distinct individual and the commitment to her absent son

Through Eva’s eyes, Charlotte is “the inconceivably peculiar mother.” As mothers, they have almost opposing approaches. Between Eva and her deceased son Erik, “there is no boundary, no insurmountable wall.” This contrasts with the relationship she had and still has with her mother, Eva having no significant place in her mother’s life and always kept at a distance. With her autonomy being limited as a child, it appears Eva could never really view herself as being a separate entity, unattached from her mother.

Striving to keep him close despite his physical absence, she remains, in a similar way, attached to her son Erik, promising to never “abandon” him. A child devoid of the love and care of their mother is bound to be upset and in that respect, Eva’s criticism towards her mother is valid. Only that it comes too late, years of accumulated anger and swallowed resentments coming down upon Charlotte in the span of one night. Her ‘mothering,’ was faulty, far from being the best but there was no reproach from Eva’s end. Out of fear of driving her mother away, she stood still and bore everything.

What is completely unjustified on Eva’s part, though, is holding her mother accountable for everything that has gone wrong in her life and their life in relation to each other, such as attributing the ultimate worsening of Helena’s illness to her leaving sooner, several years ago. As elder sisters often assume the role of the second mother to their siblings, Eva becomes the caretaker of Helena, her illness-stricken younger sister.

Undertaking conscious choices as a mother

As a child, Eva recalls being handed over to the nanny whenever she was ill or difficult. This underscores why Eva did not let Charlotte know of Helena’s presence in her home. Looking after one’s children is the responsibility of every parent, and as an individual, one is entitled to their personal interests, and when someone’s priorities are already set, it’s difficult to focus equally on multiple things. Before Eva stepped in, Charlotte sent her terribly ill daughter to a home to be looked after, which is seen as an unkind act on her part, as mothers are expected to be caregivers to their children.

From an objective viewpoint though, this is a conscious decision taken by her, as she likely wouldn’t have managed to make the time for it. There’s a sense of guilt underlying this, evident from Charlotte’s frustration at being unable to “hold her and comfort her.”

On the train ride back to her place, she says, “Why can’t she die?” reflecting upon Helena’s ever-deteriorating condition, the statement expressive of her loathing towards her. She is not the ever-loving, unconditional mother figure. Despite loving her daughters, which she does only because she feels she should, Eva and Helena are a liability to her, a hindrance to her world outside.

While the heteropatriarchal society might not be welcoming towards someone like Charlotte, Bergman reveals the complexities of human character, as neither Charlotte nor Eva can be put into the binary of good or bad. That said, the film doesn’t contemplate a woman’s pursuit of a career or the struggle to balance work and family – it delves deeper, examining the wilful emotional neglect Charlotte subjects her daughters to and the lingering guilt she carries as a result.

Although women are conditioned with the idea of motherhood, not every woman will find fulfilment in the role, and even a mother’s love can come with limits. Motherhood is a continuous process of becoming and there is no universally correct way to navigate that period. Charlotte doesn’t want to be a mother, despite being one.

Indeed, we are faced with a situation of almost role reversal, as far as conventional depictions go – the mother pursues her ambitions while the daughter is left to bear its emotional weight at home. “Autumn Sonata” confronts the often unspoken tensions in familial relationships and compels us to consider the many different approaches to motherhood, some nurturing, some distant, but all worthy of being explored with greater honesty and nuance.