India is celebrated for its linguistic diversity. However, it is this diversity that occasionally creates challenges. Political conflicts in India are often articulated through “language wars” because linguistic sentiments make it easier for the masses to choose sides. Conversely, language wars also symbolise more deep-seated socio-political conflicts of our society. A recent case in point is the hounding of Bengali migrant labourers in several states. These labourers, mainly Muslim or Dalit, are suspected of being illegal Bangladeshi immigrants or Rohingyas and hurriedly transported to Bangladesh, flouting all formal procedures in the process.

Bengali migrant labourers in New Delhi, Maharashtra, Odisha, and Assam have been facing such harassment in the last few months. The resultant political discourse has centred around the Bengali language as its speakers are now perceived to be under attack in these BJP-ruled states.

The migrant plight

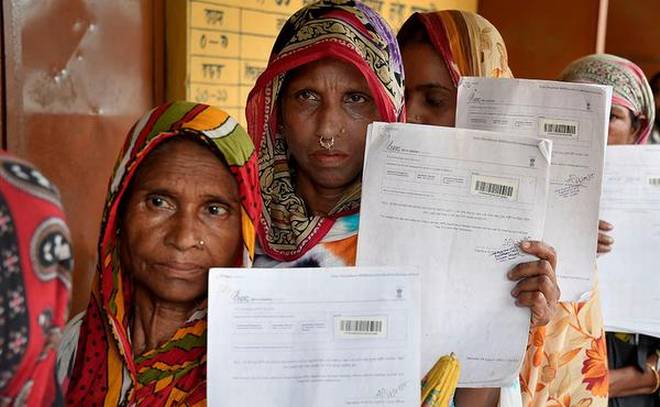

On 3 July 2025, at least six Bengali migrant labourers living in Pune were detained by the Maharashtra Police on suspicion of being illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. They belonged to the Matua community, a Namashudra Dalit community in West Bengal who had migrated to India from Bangladesh in 1947 and 1971 to escape partition violence. The BJP has been promising them Indian citizenship for decades and has used this sentiment to garner support in Matua-dominated constituencies. Matuas possess an identity card issued by the All India Matua Mahasangh in lieu of proper citizenship documents, signed by BJP MP and Union Minister of State Shantanu Thakur.

In 2023, Union Deputy Home Minister Ajay Kumar Mishra had announced these cards to be sufficient proof of citizenship for the Matuas until the CAA is implemented. Ironically, even these cards failed to prove their Indianness at present.

Assam Chief Minister (CM) Himanta Biswa Sarma recently commented that ‘writing Bengali as mother tongue in the Census documents will quantify the number of foreigners in Assam’. This provoked West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee to remind Sarma of the ‘Indian-ness of Bengali.

Nine Bengali migrant labourers have been recently detained in Chhattisgarh for failing to produce proper documents. Sweety Biwi, a resident of Birbhum, was transported to Bangladesh by the Delhi Police, despite her claiming to be an Indian. Uttam Kumar Brajabashi, a Rajbanshi (a Bengali Dalit community) farmer in Cooch Behar district, was sent a notice from Assam’s foreigners’ tribunal requiring him to prove his citizenship. Unfortunate reports of Bengali migrant labourers being directly transported to Bangladesh came streaming in from Odisha too.

The plight does not end there. India and Bangladesh share an approximately 4,000 km long border that has been mostly fenced recently. Cooch Behar (India) and Lalmonirghat (Bangladesh) are contiguous districts. In several cases, Bangladesh has denied entry to these Bengali labourers claiming they were Indian citizens. In one incident, India was forced to take back 65 people as Bangladesh refused to accept them. On 28 May 2025, 13 people remained stranded at the Zero Point in Lalmonirghat as both countries denied entry to them. Additionally, thousands of people have disappeared since they were declared “foreigners” in India.

The “foreign-ness” of Bengali

The problem began on 19 May 2025, when the Ministry of Home Affairs issued a directive to detect, identify, and deport illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and Myanmar. Hence, linguistic profiling became the easiest way to round up Bengalis working in the unorganised sector as suspected foreigners. Adding fuel to the fire, the Assam Chief Minister (CM) Himanta Biswa Sarma recently commented that ‘writing Bengali as mother tongue in the Census documents will quantify the number of foreigners in Assam’.

This provoked West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee to remind Sarma of the ‘Indian-ness of Bengali.’ She referred to notable Indians like Subhash Chandra Bose and Rabindranath Tagore who are celebrated nationally. She also evoked the National Anthem and the National Song to remind Sarma of Bengali language’s role in the formation of national symbols. However, Sarma’s comment did not refer to the foreign-ness of Bengali in India but evokes the years-long Assamese-Bengali conflict in Assam.

In 1985, more than 2,000 Bengali Muslims were massacred by Assamese Hindus, Koch, and Tiwa tribe in the erstwhile Nagaon district. Known as the Nellie massacre, this incident was a result of the Bengali Muslims wishing to exercise their voting rights in Assam to prove their Indian citizenship. The Bengali language in Assam has a troubling hsitory of conflicts, Massacres and discrimination. Himanta Biswa Sarma’s comment fans this divisive sentiment by articulating the current refugee crisis in linguistic terms.

In 1961, the Bimala Prasad Chaliha government decided to impose Assamese as the official language of the valley. Since there is a sizable Bengali-speaking population in Assam, they demanded the inclusion of Bengali as an official language. As a result, Bengalis and Assamese clashed, leading to the death of 11 Bengali Hindus in Silchar due to police firing. This movement is popularly known as the Barak Valley agitation, and a memorial has been erected at the Silchar railway station commemorating the ‘Bengali language martyrs’.

Twenty years later, in 1985, more than 2,000 Bengali Muslims were massacred by Assamese Hindus, Koch, and Tiwa tribe in the erstwhile Nagaon district. Known as the Nellie massacre, this incident was a result of the Bengali Muslims wishing to exercise their voting rights in Assam to prove their Indian citizenship. The Bengali language in Assam has a troubling hsitory of conflicts, Massacres and discrimination. Himanta Biswa Sarma’s comment fans this divisive sentiment by articulating the current refugee crisis in linguistic terms—an easy way to evoke anti-immigrant discourse in the indigenous Assamese public memory.

Language and the informal sector

Language conflicts taking an ugly turn are not new in India, and the worst-affected group is the working classes everywhere, especially the unorganised sector. The industrial cities in India witness seasonal migration of labourers from different states for various informal jobs. Brick kilns in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, for example, employ labourers from West and South Odisha and subject them to terrible working and living conditions and meagre wages, bordering on torture. Language becomes an additional barrier for the labourers to appeal to any government authority during incidents of violation. Odisha itself hires labourers from West Bengal for the informal sector, as is highlighted by the recent incidents of harassment.

A predominant Bihari population in Maharashtra works in the informal sectors, as hawkers and labourers. The Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS), led by Raj Thackeray, was responsible for widespread violence against Hindi-speaking workers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in 2008. There were reports of killing workers and amputating hawkers, which led to a mass exodus of North Indian workers from the state. Consequently, the local industries suffered a loss of Rs. 500 crores. The MNS had recently launched another agitation where they harassed even formal sector employees from North India.

Whom does a language movement other?

Over the last few months, India witnessed a spate of debates regarding Hindi imposition by the Union government. The anti-Hindi campaign was led by the ruling DMK government of Tamil Nadu, which vehemently critiqued the National Education Policy’s three-language mandate. However, this anti-Hindi sentiment in Tamil Nadu has not translated into violence against Hindi-speaking migrants in the state.

The government has actively foiled efforts by the BJP in Tamil Nadu to evoke animosity among the Hindi-speaking migrant labourers against locals. Instead, the larger Dravidian anti-Hindi discourse seeks to expose the Hindutva state’s covert mechanisms to undermine India’s federal structure. Contrarily, any other model of linguistic pride that others individuals lead to their linguistic profiling as “foreigners” and succeeds by intimidating or chasing them away.

Language conflicts taking an ugly turn are not new in India, and the worst-affected group is the working classes everywhere, especially the unorganised sector. The industrial cities in India witness seasonal migration of labourers from different states for various informal jobs.

Seen in this light, one will observe that the linguistic profiling of migrant workers is not being done on the basis of the Bengali language alone. In a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, former Congress MP Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury said that the migrant labourers were being targeted as the ‘accent of language spoken are similar to the people of Bangladesh’. Speaking in Bengali is not synonymous with sounding like a Bangladeshi national. In fact, when Mamata Banerjee demanded an apology from Sarma, he was quick to point out the difference between indigenous Bengalis and Bangladeshi infiltrators. The issue here is about othering a language community whose identity has several negative connotations associated with it in India: foreigners, illegal immigrants, infiltrators, job stealers, criminals, etc. Hence, Mamata Banerjee’s appeal to Bengali-speakers to agitate against the apparent anti-Bengali sentiment of the BJP will be reduced to a symbolic linguistic unity if these pervading myths are not debunked in parallel.

Unless we address these underlying biases propagated by the Indian popular media and the State against a refugee community, the working classes will continue to be harassed based on their linguistic identity. In turn, India needs to formulate a proper mechanism to address the ongoing refugee crisis. The absence of the same will lead to such arbitrary measures to other individuals on as flimsy grounds as the accent of their speech.

About the author(s)

Solanki Chakraborty is a PhD scholar at the Centre for English Language Studies, University of Hyderabad. Her work is on the history of language teaching and learning in colonial India. She is interested in reading and writing about pedagogy, language politics in India, and food history.