Mx. Yashika’s story begins not with triumph, but with a tremor. One that cuts through the tattered jacket of solidarity in India’s trans rights movement. A Dalit trans scholar from Saharanpur, she recently became the target of public, casteist allegations by none other than a senior member of the Uttar Pradesh Transgender Welfare Board, per a January 2025 report by The Probe.

The Hindu reports, Devika Devendra S. Manglamukhi, alleged that Yashika had fraudulently obtained her caste and transgender identity certificates. These are claims which Yashika vehemently denies and has legally contested. The notice served by Yashika (with pro bono help from Chambers For Justice, a New Delhi-based law firm) demands not just a retraction, but reparations for a betrayal that feels as institutional as it is personal.

“Caste atrocities against Dalit trans and queer people were never even taken into consideration,” she says.

At stake here is more than one person’s dignity. It’s the erasure of Dalit trans voices from movements that claim to speak for all trans people. It’s the reproduction of caste supremacy within LGBTQIA+ spaces that purport to be inclusive. And it’s the heartbreak of being ghosted (not just by dominant-caste-led queer institutions) but also by platforms dedicated to Dalit rights.

As Yashika puts it, “[Most people] ignore Dalit trans issues.”

What does the notice reveal?

On July 6, 2025, Devika posted on Instagram, alleging that Mx. Yashika had forged her Scheduled Caste and Transgender ID certificates.

These accusations were echoed in news platforms like UP Tak and TNF Today (the latter has since been deleted but was referenced in the legal notice served by Yashika), claiming NHRC intervention, which the legal notice debunks as entirely fabricated.

The UP Tak report falsely stated: “Yashika (…) has violated the rules and fraudulently got two certificates made for herself. One of these is a Scheduled Caste certificate, and the other is a Transgender Identity Card issued by the District Magistrate.”

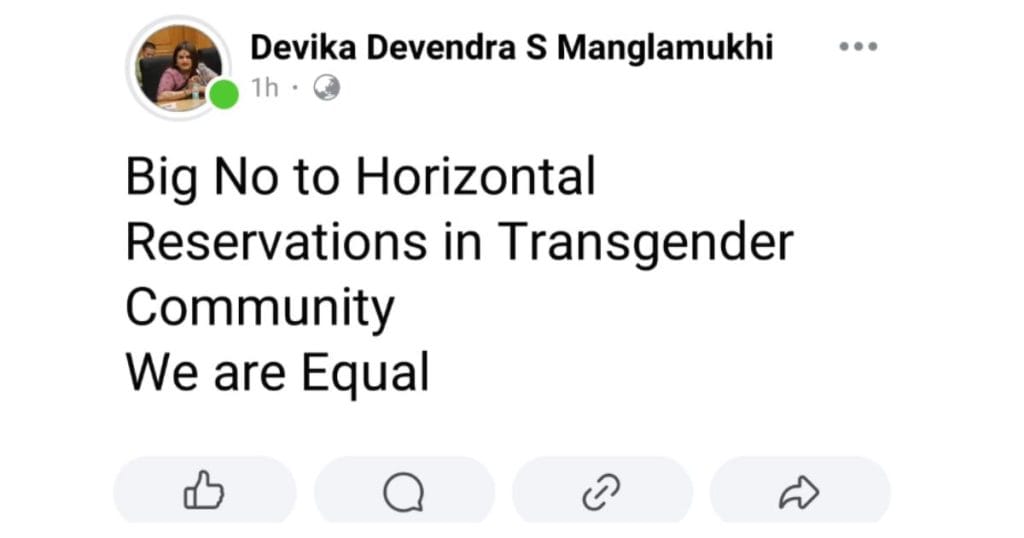

The article further insisted that trans persons should only be recognised under the OBC category as per a 2014 decision, thus implying that caste-based reservations are illegitimate for trans individuals. Such assertions not only misrepresent the NALSA judgment but also overlook the lived realities of caste and gender-based oppression.

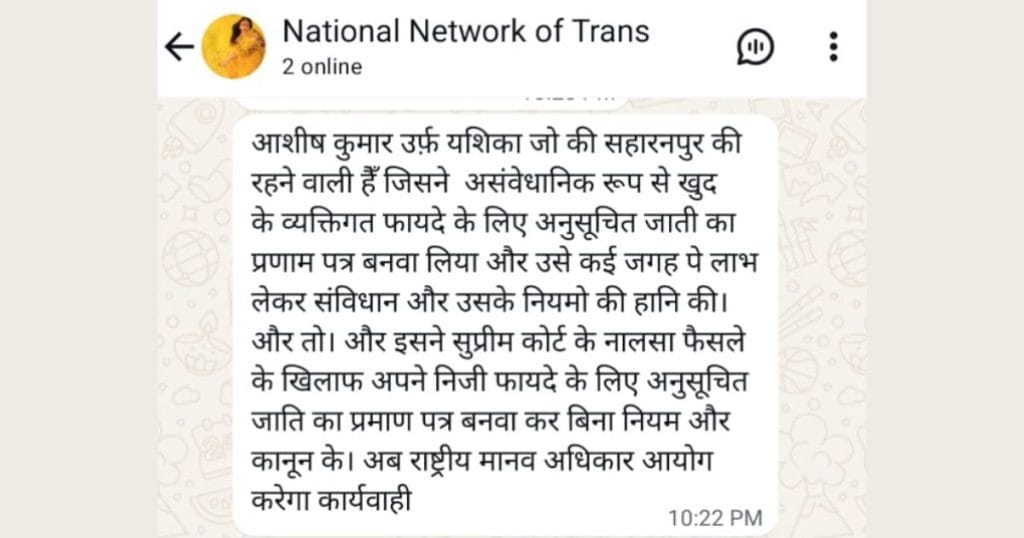

SDM Ankur Verma, cited in the same report, clarified that his office had received no formal complaint. Despite this, Devika allegedly weaponised WhatsApp groups like ‘National Network of Trans’ and ‘Webline Transgender’ to circulate defamatory content, including urging others to shame Yashika. The notice also claims Devika “used and circulated photographs of [Yashika] without her consent, which constitutes a gross invasion of her privacy.”

Over and above deadnaming her repeatedly, the screenshots from these groups reference Yashika’s caste identity, her father’s name, and calls to ostracise her.

The legal notice that was issued was acted upon by Advocate Sourabh Rai of Chambers for Justice, who accused Devika of criminal defamation under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita and of violating provisions under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act and the IT Act.

Devika has previously publicly targeted another Dalit trans activist. An April 2025 report by The News Minute says she had also levelled similar accusations against activist Grace Banu, another fierce advocate of horizontal reservation, at the Talkatora Police Station. She alleged that Grace had robbed and threatened her on December 22, 2024.

The parallels are impossible to ignore.

Transgender activists who advocate for horizontal reservation are among the other complainants listed by Devikai in her formal complaint. Ritwick Das, an activist based in Lucknow and Delhi, and Jane Kaushik, an activist based in Delhi, are among them.

A pattern of casteism within queer spaces

Yashika is not new to exclusion. She tells FII that while pursuing an M.A. in Human Rights at Panjab University, Chandigarh, she was denied hostel access solely due to her gender identity. This was until a 2022 Punjab & Haryana High Court order forced the administration to comply.

“My family never helps me. I experienced gender exclusion from Dalit spaces as well as caste oppression among trans or cis people in the upper caste,” she explains. The very institutions she turned to for protection replicate the same hierarchies she tried to escape.

The current attack, she alleges, stems from a long-standing disagreement over reservation policy. While Yashika and several Dalit trans activists advocate for horizontal reservations (recognising caste and gender identity as overlapping systems of oppression), Devika has publicly argued that all trans persons should not be categorised under SC/ST/OBC on the WhatsApp group named National Network of Trans.

Yashika believes this erases the unique oppression faced by Dalit trans individuals and flattens the community into a monolith. The structural vulnerability deepens these wounds. “I never had family support. I faced intentional and systematic exclusion,” Yashika says.

Even in queer spaces, caste determines who gets platformed and who gets policed. In Uttar Pradesh, she adds, “Dalit trans persons are living in fear, which is why they don’t come out openly in Uttar Pradesh,” due to fear of harassment from both the state and dominant-caste queer groups. “I feel very unsafe due to casteism and misgendering.”

Where is our media?

The silence around Yashika’s case is deafening. Despite the clear legal record and digital evidence of defamation, several well-known platforms (including those focusing on Dalit rights) have refused to cover her story. “Some promised they would and ghosted me,” she says.

The media’s silence only shows their underlying discomfort with intersectionality.

Dalit trans persons often find themselves erased from both the Dalit movement (which tends to be cis-heteronormative) and the queer movement (dominated by upper-caste voices). “They ignored our visibility and alienated us,” Yashika says. “There is no Dalit liberation without the appropriation and inclusion of Dalit trans persons in the Dalit movement.”

Dalit Queer India, a collective Yashika is in conversation, affirmed her experience. “They told me they’ve faced the same,” she recalls. “They said the only way forward is to create our own media spaces. The world doesn’t want us to exist, so we have to write our own histories.”

In a country where Savarna narratives dominate even within activist spaces, such calls to build autonomous platforms are revolutionary and necessary.

In the middle of this storm, Yashika managed to achieve something monumental. In June 2025, she qualified for the UGC-NET, earning eligibility to be an Assistant Professor. “It means a lot,” she says, her voice breaking. “I want to thank Babasaheb Ambedkar and Buddha. I recall Ambedkar once said: Those who don’t know history, don’t make history.”

This is not just a personal milestone but a political statement. It asserts the right of Dalit trans persons to participate in public life, academia, and governance. It stands in direct contrast to the degrading ‘good trans person’ narrative being pushed by Devika and her allies.

Mx Yashika is also part of a broader national demand: the implementation of horizontal reservation for trans persons in public education and employment.

“The Dalit trans community all over India demanded to implement horizontal reservation for transgender persons in educational institutions and public employment, especially in Uttar Pradesh,” she says. “I want to tell the Union Government to consider horizontal recognition of trans persons along with their caste identity in the upcoming caste census.”

When the trans movement hurts its own

The pain in Mx. Yashika’s voice isn’t just from this smear campaign. It’s from being betrayed by movements she’s worked tirelessly to uplift.

This isn’t the first time Devika has targeted Dalit trans activists, and it likely won’t be the last unless accountability is demanded. That a senior welfare board member can allegedly defame a vulnerable trans-Dalit woman without due process should alarm us all.

Yashika’s story is not just hers.

It’s about what happens when the margins are marginalised again, by the very movements meant to protect them. When gatekeeping replaces solidarity, when institutional power is wielded not for advocacy but for personal vendettas, the movement fails.

Queer and Dalit spaces must do better. They must commit to intersectionality not as a buzzword but as a practice. And they must make room for our Yashikas all over the world…not just in times of triumph, but especially in moments of trial.

About the author(s)

Sohini (they/she) hails from Calcutta and loves to explore and write about all things society, culture, gender. With a background in journalism and English literature - they have finally been able to make having heartfelt conversations a huge part of their life outside of boxes.

Comments:

Comments are closed.