Following the Pahalgam attack, the Ministry of Home Affairs set a 30-day limit for states to identify and verify the credentials of those suspected to be “illegal” immigrants. What followed was detentions based on linguistic and religious profiling and deportations without due process, with some Indian citizens wrongfully deported to Bangladesh.

Rise of the Hindutva ‘infiltration’ narrative

The Hindutva bogey of Bangladeshi “infiltration” has once again come to the forefront in the run-up to the Bihar elections. Following the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls in Bihar and claims of suspected foreigners being on the voters’ list, efforts to purge “illegal” immigrants have gained momentum in northern India.

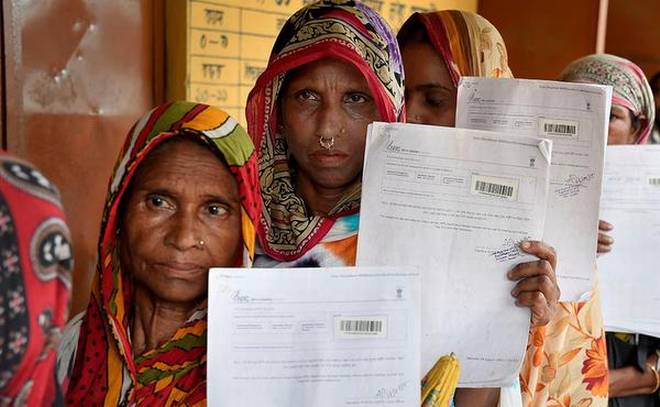

Bengali migrant workers, especially those who are Muslims, have borne the brunt of these ‘illegal’ immigration crackdowns. On July 22, 2025, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee claimed that Himanta Biswa Sarma’s BJP-led government in Assam had sent ‘NRC notices’ to residents of West Bengal.

As detention of Bengali migrant labour spread across BJP-ruled states, fearing the same fate, many sanitation workers, mainly Muslim workers, were forced to leave Gurugram. Speaking to the Times of India, a sanitation contractor said, ‘Nearly 60-65% of our workforce are Bengali-speaking Muslims. After the raids began, there was panic. Some were beaten; others heard rumours and just left. Now they have gone to nearby districts or back to their villages.’

Lack of safeguards and due process

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is intended to be a comprehensive record of all Indian citizens, maintained in order to facilitate the easy identification of ‘illegal’ immigrants. As of now, Assam is the only state in the country to have it in use. However, the NRC is designed in a way that enables arbitrariness and the circumvention of due process.

The recent spate of detentions and crackdowns suffers much the same issues of rights and due process violations. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has asserted that the Indian government has sent numerous Bengali Muslims to Bangladesh without due process by claiming that they are ‘illegal immigrants’.

A ‘local official’ is empowered to decide if a person will be added to the list; there is little clarity on what documentation constitutes proof of citizenship; and contradictory and arbitrarily enforced evidentiary rules exist. The onus of disproving the citizenship claims of a foreigner is not on the state; in fact, the burden is shifted onto individual citizens who have to present documentation and prove they are Indian citizens if called upon to do so.

In Assam, the only state to have carried out the NRC exercise so far; quasi-judicial bodies called as Foreigners Tribunals (FT) are tasked with resolving matters concerning citizenship and ‘illegal’ immigration. These bodies have little or no constitutional or procedural safeguards and operate without the rigorous legal standards and accountability applied to regular judicial bodies. The ‘NRC notices’ sent to individuals in Bengal originated from one such Foreigners Tribunal in Assam.

Flaws in the NRC and Foreigners Tribunals

A recent study found a plethora of issues with these tribunals, including several rights and due process violations. The report highlights issues of arbitrariness in decision-making, a lack of safeguards, and rejection of oral and documentary evidence. It also highlighted the vulnerability of FTs to executive interference. The report concludes with, ‘The FT system in Assam is not merely a flawed mechanism in need of reform—it is a legally unsustainable regime that violates the most basic tenets of constitutional democracy and international human rights.’

The recent spate of detentions and crackdowns suffers much the same issues of rights and due process violations. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has asserted that the Indian government has sent numerous Bengali Muslims to Bangladesh without due process by claiming that they are ‘illegal immigrants’. Elaine Pearson, HRW’s Asia director, said, ‘India’s ruling BJP is fuelling discrimination by arbitrarily expelling Bengali Muslims from the country, including Indian citizens.’ She further added, ‘The authorities’ claims that they are managing irregular immigration are unconvincing given their disregard for due process rights, domestic guarantees, and international human rights standards.’

Elaine Pearson, HRW’s Asia director, said, ‘India’s ruling BJP is fuelling discrimination by arbitrarily expelling Bengali Muslims from the country, including Indian citizens.’ She further added, ‘The authorities’ claims that they are managing irregular immigration are unconvincing given their disregard for due process rights, domestic guarantees, and international human rights standards.’

Among the ‘illegal’ immigrants returned to Bangladesh, many were Indian citizens. The Guardian reported that when Indian citizens asked to cross the border to Bangladesh and tried to resist, they were threatened at gunpoint and forced to cross over, only for Bangladesh to send them back. Nearly 200 people have been returned to India after being found to be Indian citizens, including four Bengali migrant workers from Mumbai.

These deportations aren’t formal deportations executed through legal and official channels either. The mechanism employed is a ‘push back’ approach where individuals are taken to the border and forced to cross over to the Bangladeshi side. Assam’s Chief Minister, in a May 2025 press conference, stated that his government had decided to rely on this ‘push back’ system. The Indian citizens who were returned after being sent to Bangladesh have also had to cross the border back to India on foot. This non-legal, informal approach leaves Indian citizens carelessly sent to Bangladesh on their own, to either find their way back or remain stranded.

Targeting the marginalised

The ongoing detention and deportation drives disproportionately target the marginalised by design. The majority of the Bengali detainees are migrant and informal labourers and often Muslims. In targeting a class of people whose economic status makes legal remedies and safeguards inaccessible, enables them to slip through the cracks more easily, and makes the chance of possessing extensive documentation more unlikely, the government essentially has a free hand to do as it pleases.

What constitutes proof of citizenship is limited and arbitrary. The Aadhaar, PAN, and ration cards have been ruled out as proof of citizenship by the government. Voter IDs are often overlooked because of the belief that ‘illegal’ immigrants easily find their way onto the voters’ list.

The government holds that birth and domicile certificates are the only valid proof of citizenship. There is little clarity as to what else constitutes proof. An Indian passport, a document that categorically states the bearer’s nationality as being Indian and by its very nature and purpose can only be issued to a citizen, also doesn’t seem to hold much value. However, the demands for these documents to prove citizenship and the lack of clarity surrounding the matter make the poor the most vulnerable.

The government holds that birth and domicile certificates are the only valid proof of citizenship. There is little clarity as to what else constitutes proof. An Indian passport, a document that categorically states the bearer’s nationality as being Indian and by its very nature and purpose can only be issued to a citizen, also doesn’t seem to hold much value.

In a country where nearly half the people earn less than INR 500 per day—27.5 percent of whom earn less than INR 100—it is likely that many don’t hold passports, property papers, or vehicle registrations. The migrant and informal workers who are the targets of these detentions and deportations are also less likely to have received formal education, reducing the likelihood of possessing documents like school-leaving certificates or board marksheets.

Domicile certificates are issued by states and can only be sought after a number of years of continuous residency in that particular state. These numbers can widely vary and can range between 3 and 15 years. Migrant labourers, due to the informal nature of their work and job insecurity, have to move around in search of work, making it harder for them to meet the requirements to get a domicile certificate.

As for birth certificates, though legally required, not every Indian citizen has one. For one, the registration of births wasn’t a legal requirement until 1969. Further, inaccessibility, lack of awareness, and a prevalence of homebirths make possession of birth certificates less likely among those in rural areas and among the poor and marginalised. Data supports this. A 2020 IndiaSpend survey found that 35.7 percent of children under five did not have birth certificates. The analysis also showed that children born before 2005 or belonging to the poorest sections of society, scheduled castes and tribes, and families with no formal education are less likely to have their births registered. In 2000, only a little over half of the births in the country were recorded.

Socioeconomic vulnerability of migrants

However, even when someone possesses the required documents, as found in the above-mentioned FT study, arbitrary evidentiary rules are applied and documentation is rejected. This holds true for the recent deportations as well. The Deccan Herald reported the case of one such migrant detainee, whose family provided his Aadhaar, PAN, Voter ID, life insurance policy, and vehicle registration to prove his citizenship, but the authorities rejected all these documents as valid proof. In another instance, a Bengali migrant worker residing in Mumbai was sent to Bangladesh despite the West Bengal government’s intervention and the necessary documentation to prove his citizenship being presented. India’s poor are often document-poor, making them the most vulnerable to such detentions, deportations, and NRC exercises. Muslims, as India’s poorest religious group, face increased risk due to the overlap between their economic status and religious identity.

In 2024, the weeks before the Jharkhand election saw claims of ‘infiltration,’ land jihad, and population jihad by the BJP. Which is why the timing of these crackdowns is suspect. These crackdowns began in the shadow of mounting public dissatisfaction over the handling of the ceasefire and pressure from the opposition for answers and transparency following Pahalgam and Operation Sindoor. And only months away from Bihar’s election, where ‘illegal’ immigration and ‘infiltration’ have become central issues. Doubling down on the ‘infiltration’ narrative at this point in time comes with the prospect of electoral gains in Bihar and electoral appeasement in the remainder of the states for the BJP.

About the author(s)