Last year, in 2024, I landed in Japan eleven months postpartum, still carrying the deep, bone-level fatigue of a year spent almost entirely in service of another small, insistent life. In India, that service had been relentless, first through the exclusive breastfeeding that anchored me to one place for hours at a time, and then also through the invisible choreography of care: the unbroken chain of tasks that bound me, physically and symbolically, to the role of primary parent.

Public spaces in India make this arrangement feel inevitable. Men’s restrooms rarely accommodate the work of babies, no changing tables, no bottle-warming counters, no quiet corners to soothe a crying baby. When women’s restrooms do provide a “baby room,” the assumption is clear: only mothers will step inside. The architecture of care is built for women alone. My husband, even when willing, could rarely step seamlessly into my role.

That is why my arrival at Narita Airport brought such unexpected relief. The men’s restroom had a diaper-changing station. There was a dedicated women’s baby room. And most remarkable of all, there was a separate, gender-neutral baby care space, open to anyone. Both my husband & I can do the changing & washing together, or I could nurse the baby, and my husband handled the changing and washing. For once, the responsibility did not cling to me like a second skin.

Over the next two weeks, I saw it everywhere—in train stations, department stores, even tiny cafés. Japan’s urban infrastructure made care visible, shareable, and possible for anyone. It struck me how quietly radical this was: that the built environment could so effortlessly redistribute the work of parenting.

Back in India, the picture is starkly different. Finding a feeding room or diaper-changing station is still a privilege reserved for a handful of malls, airports, or certain elite public spaces. This absence of even basic facilities is not just an inconvenience; but it reflects a deeper policy flaw. Our public infrastructure is designed with the assumption that caregiving is, by default, a woman’s duty. For queer fathers, widowers, single dads, or any father who simply wants the freedom to take his child out alone, this becomes a barrier to public life and a sign of how little caregiving, of any kind, receives institutional support.

Recent court decisions have reinforced this pattern. In Maatr Sparsh, An Initiative by Avyaan Foundation v. Union of India (February 2025), the Supreme Court acknowledged the rights of mothers and infants to breastfeed, nurse, and receive childcare in public spaces and placed a duty on the state to provide supporting infrastructure. Yet the judgment left fathers, partners, and other caregivers entirely outside the frame. It did not imagine caregiving as a shared social responsibility; instead, it crystallised the old belief that infant care belongs to the mother alone.

Finding a feeding room or diaper-changing station is still a privilege reserved for a handful of malls, airports, or certain elite public spaces. This absence of even basic facilities is not just an inconvenience; but it reflects a deeper policy flaw.

A month earlier, in Rajeeb Kalita v. Union of India, another bench had directed all High Courts to ensure court complexes contained rooms linked to women’s washrooms equipped with feeding stations and changing facilities. The Government was also told to implement the Ministry of Women and Child Development’s advisory on creating breastfeeding and childcare facilities in public spaces, government offices, and public sector workplaces. Though intended to increase women’s workforce participation, this framing again tethered caregiving facilities to women, excluding fathers and non-maternal caregivers from the picture.

By focusing exclusively on mothers, such policies risk deepening the “double burden” women already bear: engaging in paid work while continuing to shoulder unpaid care work at home. Indian men spend, on average, just 15 minutes a day on childcare; Indian women spend nearly 70 minutes, almost double the global average for women, according to a study by IIM Bangalore. Without structural change to how care is distributed, increasing women’s public participation will remain an unfinished promise.

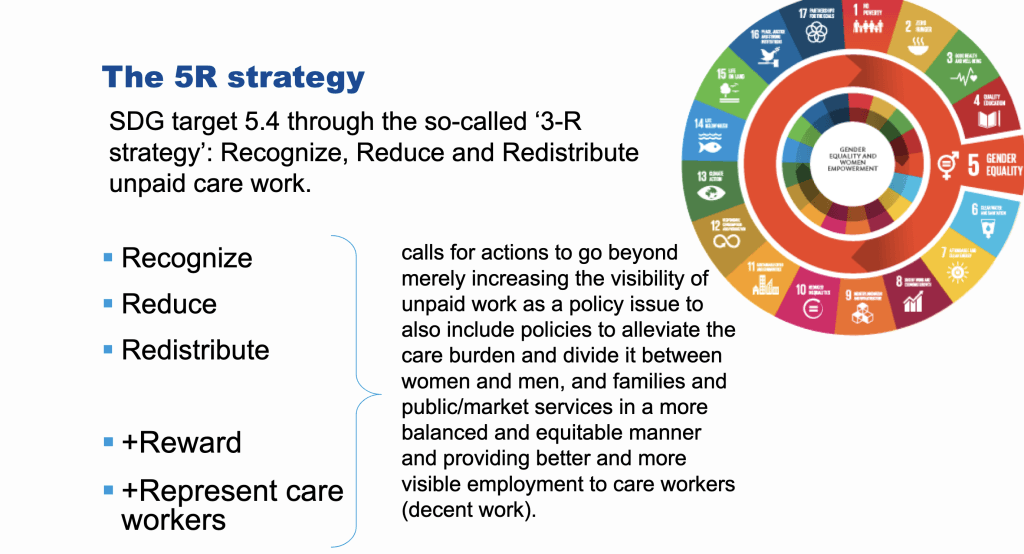

Legal scholar Sandra Fredman describes substantive equality as having four interdependent dimensions: redressing disadvantage, challenging stigma and stereotypes, enhancing voice and participation, and transforming structures. All four must operate together. Neglecting one can undo the progress achieved by the others. The “Three Rs” framework, recognising, reducing, and redistributing women’s unpaid care work, offers a practical roadmap. But redistribution is impossible if caregiving spaces remain physically and symbolically linked to women alone.

An alternative approach is both obvious and urgent: designate a portion of all public and workplace childcare facilities as gender-neutral. Doing so would promote equality within heterosexual couples and acknowledge the realities of single fathers, queer parents, and other non-traditional families. This is not just a question of fairness; it directly serves the child’s right to life, care, and security, rights the Supreme Court itself has affirmed.

Gender-neutral baby care infrastructure would promote equality within heterosexual couples and acknowledge the realities of single fathers, queer parents, and other non-traditional families.

Other countries have already taken steps in this direction. In 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama signed the BABIES Act, requiring all male restrooms in public federal buildings to have baby-changing stations. As reported by the BBC, a widowed father recalled the humiliation, decades earlier, of waiting outside women’s restrooms to ask strangers if he could enter to change his baby’s nappy. That humiliation, for many fathers, remains real today.

India must move beyond this outdated design. Childcare rooms, feeding spaces, and changing stations should be delinked from women’s restrooms and reimagined as independent, gender-neutral baby care facilities accessible to all parents. Only by enabling fathers to participate equally in caregiving can we dismantle the entrenched gender divide in both public and private life. Legal and policy reforms must reflect this truth. Anything less is merely reinforcing the very imbalance we claim to be dismantling.

About the author(s)

Vanita is a lawyer by training and writes stories at the intersection of business & public policy, law, regulations and building inclusive workplaces. She is a Staff Writer for The Ken.