“If two minors have sex, is it illegal?” is one of the most commonly asked questions by adolescents in workshops taken by Pratisandhi across institutions in India. With so much curiosity around sexual activity stemming from a deep silence in our curriculum that refuses to address questions related to sexual and reproductive health beyond anatomic depictions in biology textbooks, it is natural for students to seek answers. But what if the child does not have access to trustworthy adults who are willing to provide legitimate answers? Pornography, friends, and the internet become the most likely sources.

Amidst this teen curiosity and uncertainties, the Indian government has taken a strong stance against amicus curiae and Senior Advocate in the Supreme Court, Indira Jaising’s demand to redefine the word ‘child’ in Section 2(d) of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012.

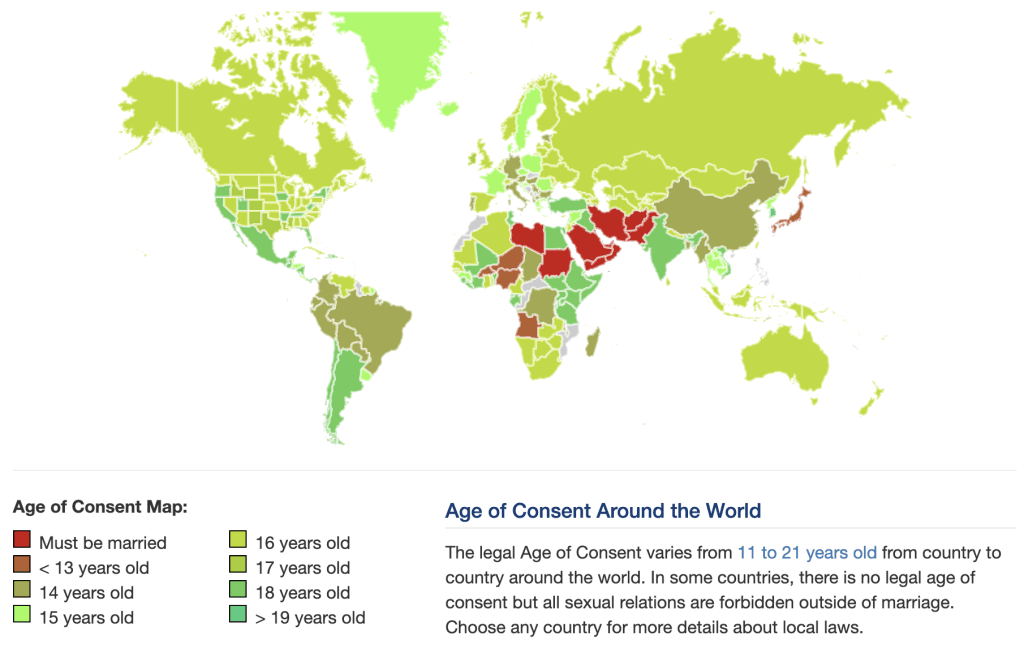

As per this law, any sexual activity with a person under 18 is criminalised, regardless of consent. The provision defines ‘child’ as any person below the age of 18 years, thereby putting a blanket age of consent and penalising any sexual activity, whether consensual or non-consensual, between partners, where either one is legally a ‘child’.

Ms. Jaising has argued for the statutory age to be lowered to 16 years to exempt individuals aged between 16 and 18 years, engaging in consensual sexual activity evolving from voluntary relationships, from the penalties stated in the POCSO Act.

Decriminalising consensual adolescent sex

Ms. Jaising has deemed the criminalisation of sexual activity between consenting adolescents, aged 16 to 18 years, as arbitrary, unconstitutional and against the best interests of children.

Demanding exemption from the POCSO Act, Section 375 of the IPC and its corresponding provision in Section 63 of the BNS, which prescribes punishment for rape, Ms. Jaising invoked the ‘close-in-age-gap’ exception, which is also called the Romeo and Juliet clause.

“Such an exception would preserve the protective intent of the statute while preventing its misuse against adolescent relationships that are not exploitative in nature,” submitted Ms. Jaising.

The age of consent was initially 16 years

Much to the reader’s surprise, the age of ‘consent’ for marriage was initially 10! Although it is arguable how much of it was coerced. From 10 years in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860, the age of consent has progressively increased to 14 years and 16 years through amendments in 1925 and 1940, respectively. In 1978, the age of consent for marriage was increased to 18 years for females and 21 years for males by an amendment to the Child Marriage Restraint Act.

However, when it came down to consent for sexual activity, the age of consent was increased to 18 years in 2013 after the Justice Verma Commission’s recommendation, and this change was implemented through the POCSO Act.

The present case challenges the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013, which came following the Justice Verma Committee’s report in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya gang rape and murder case in December 2012.

Ms. Jaising’s principal arguments include adolescents having attained sexual awareness as a result of puberty, which now occurs at a faster pace than before. This enables them to give mature consent to sexual activity.

Science says sex?

Data collected by Pratisandhi supports Ms Jaising’s argument that adolescents are attaining the age of sexual awareness earlier now. In a survey with over 220 respondents from across 50 DU colleges, it was recorded that the average age of engaging in any kind of sexual activity was 17.5 years and for sexual intercourse, it was 20 years, with over 56% respondents considering themselves sexually active.

Research by the World Health Organisation (WHO) has consistently shown that early childhood intervention through effective implementation of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) reduces sexually risky behaviour and delays the age of sexual debut, increases knowledge about sexual and reproductive health, and raises awareness about the implications of engaging in early sexual activity.

In a survey with over 220 respondents from across 50 DU colleges, it was recorded that the average age of engaging in any kind of sexual activity was 17.5 years and for sexual intercourse, it was 20 years, with over 56% respondents considering themselves sexually active.

UNESCO defines CSE as “a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality.” Such a curriculum approaches sexuality positively and emphasises the values of inclusivity, bodily autonomy, respect, non-discrimination, equality, empathy, responsibility and reciprocity.

By reinforcing a healthy and positive attitude towards bodies, puberty, relationships, sex and family life, CSE can not only reduce the risks of teenage pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases and gender-based violence, but also extends beyond adolescence to contribute towards long-term well-being.

As per data provided by the National Institutes of Health, arguments against lowering the age of consent are that it might result in younger children being more engaged in sexual activity and take the chance away from children who do not wish to engage in the sexual act, and from the claim that it is against the law.

It is also said that young people are not emotionally mature enough to engage in sexual activity, regardless of cognitive competence. This is complemented by neuroscientific evidence that says that the adolescent brain undergoes significant changes throughout the teens and beyond.

But the same NIH study discussing emotional maturity on the parameter of impulsivity shows that it significantly decreases only by the ages of 22-25 and 26-30 years. So, would this make consent by individuals aged up to at least 25 years invalid?

NIH says that studies on the median age of menarche in girls prove that a majority of girls aged 14 are physically mature to engage in sexual activity and that they are capable of analysing the risks and benefits as a 21-year-old.

Also, the strongest arguments in favour of lowering the age limit are the decriminalisation of freely given sexual consent and access to safe sexual health services without the fear of being penalised for having engaged in an illegal activity.

NIH says that studies on the median age of menarche in girls prove that a majority of girls aged 14 are physically mature to engage in sexual activity and that they are capable of analysing the risks and benefits as a 21-year-old.

An example of this is the Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority case of 1986 in the United Kingdom where on the principle of upholding ‘the best interest of the minor’, a local doctor was found not guilty of a criminal offence by providing contraception to a minor child who had lawfully consented to sexual intercourse and gotten impregnated. Similarly, POCSO provisions must take into account the role of medical practitioners in providing care in the best interests of a 16+ year old where there is no evidence or report of abuse.

These instances emphasise why CSE must be the “robust and non-negotiable shield to minors”, rather than the age of consent, which the Centre argues.

Judicial Confusion and Teen Dilemma

Calling its judgment not a precedent and exercising powers granted by Article 142 of the Constitution to do ‘complete justice‘, the Supreme Court acquitted a man aged 25 years old under POCSO of a 20-year jail sentence on May 23 2025.

The victim told the Calcutta High Court (HC) that she voluntarily entered into a relationship with the accused, married him and birthed a child, “out of her own volition“. The court then reversed the Trial Court’s conviction for rape and kidnapping under the POCSO Act of the accused.

The Supreme Court noted that it was not the alleged crime, but the legal proceedings and the “significant failures of the POCSO Act” that traumatised the victim and put the family in emotional and financial distress.

But last month, the Bombay High Court refused an application to quash a proceeding under the POCSO Act, the IPC and the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2009, involving the accused’s relationship with the 17-year-old victim.

Holding that it awaits clarification by the centre, the court refused to entertain the application, which stated that there was a consensual relationship between the victim and the accused.

Centre strongly opposes lowering the age bar

Additional Solicitor General Aishwarya Bhati stated in the written submissions, “Introducing a legislative close-in-age exception or reducing the age of consent would irrevocably dilute the statutory presumption of vulnerability that lies at the heart of child protection law.”

The Centre cited a 2007 Ministry of Women and Child Development report, which found that 53.22% of children reported facing one or more forms of sexual abuse, out of which 50% of the abusers were persons in positions of trust or authority.

“The report concluded that children are particularly vulnerable when the offender is a known figure, as the abuse is concealed, normalised, or silenced through emotional manipulation or fear,” argued the Centre.

However, the report does not clarify how many of the 12,447 children sampled were adolescents aged 16 to 18 years old. The sample size encompassed a broad range of ages within the child and adolescent population, including the spectrum of experiences, which includes children in institutional care, living on the streets and those engaged in child labour.

Is the Will of the Parliament that of the People?

The question asked by a 10th grader in a workshop by Pratisandhi about whether sex between two minors is illegal is a pertinent legal anomaly in POCSO cases. Even though the Act is a gender neutral legislation, males have faced arrest and detention in such cases, while females have had to go through the trauma of legal processes. This is in addition to the social and familial consequences that the minors might have to face.

The Centre has asserted that the definition of a “child” as a person below 18 years is a deliberate choice arising out of its constitutional duty to protect children. It said that this legislative position embodies the collective will of Parliament and cited other laws where the age of consent was 18.

The submissions maintained that the government was abiding by the constitutional provisions to protect women and children, and with India’s commitment to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). This convention defines a minor as anyone under 18 years old and regards sexual activity with such a person, regardless of consent, as rape.

Centre and Children Mirror Confusion

Even as the Centre has taken a strong stance against consensual sex between adolescents, in its previous submissions, it has allowed for judicial discretion to be exercised on a case-by-case basis in adolescent relationship cases.

The ‘Gillick Competence’ test, established in the UK case discussed previously, assesses on a case-by-case basis whether the minor has “sufficient understanding and intelligence to understand fully what is proposed,” rather than arbitrarily penalising consensual decision making. This is similar to the principle of the close-in-age-gap exception and ‘mature minor’ doctrine practised in India that recognises that some individuals under the age of 18 may possess the maturity and understanding to make healthcare decisions by and for themselves.

However, this legal ambiguity leads to a lacuna in the law and leaves adolescents at the behest of judicial decisions that are inconsistent across jurisdictions.

In a country where high schoolers are confused about whether one can get pregnant without having sex, the reality of watching porn as a teenager and whether having dreams of sex is safe—all of these have been asked in the workshops—How can the government continue to dismiss the importance of CSE?

A student asked why 18 is the legal age of consent, and this makes one ponder about what happens at midnight when one turns 18, that they attain a level of maturity in all spheres, political, sexual, legal, etc.

The Pratisandhi question bank is filled with such innocent questions, and one stands out: “How do I ask for consent?” The question is not about giving consent anymore. Many people do not know that they exercise this right.

The government strongly believes that minors lack the legal and developmental capacity to give meaningful and informed consent in matters involving sexual activity. Possibly, this is why Ms. Jaising’s plea to shift the focus to providing CSE rather than criminalising the natural processes of attraction and sexual curiosity is even more necessary.

Pratisandhi, a not-for-profit organisation based in Delhi, works towards advancing sexuality education in India by collaborating with institutions for programs, workshops and lectures while publishing guides, manuals, newsletters and blog articles as resources for advocacy, figure study or curiosity.

About the author(s)

Second year student of Media Studies at CHRIST (Deemed to be University), BRC, Bangalore. A trained Kathak dancer, theatre artist and political nerd.