Trigger Warning: Domestic Violence, Violence against Women and Murder

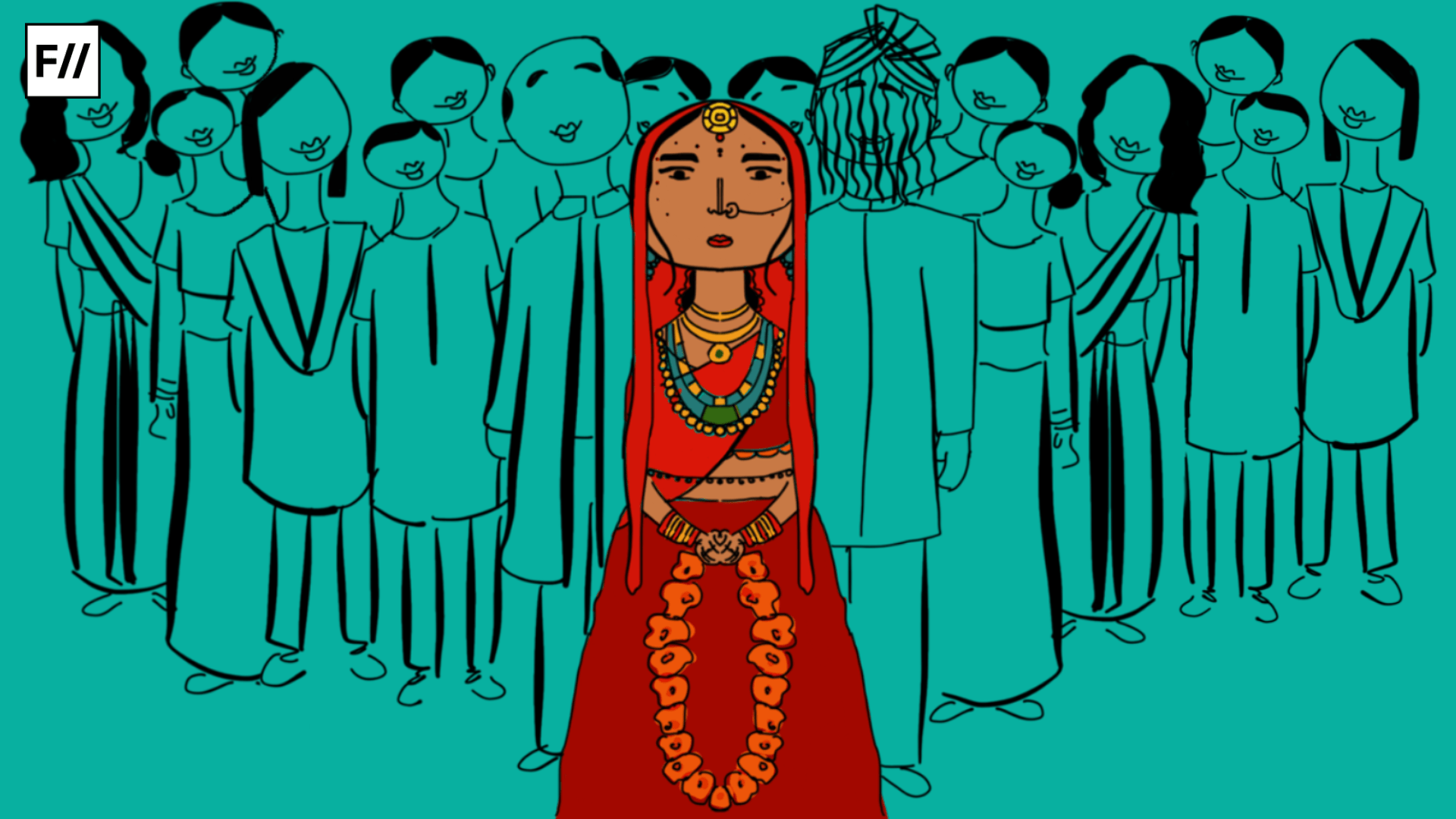

Almost 18 women are killed every day in India in disputes over dowry – one every 80 minutes. NCRB data shows that in 2022 alone, 6,450 cases of dowry deaths were recorded across the country, a figure that has barely shifted in five years despite the practice being outlawed more than six decades ago.

Behind the statistics are stories like that of 26-year-old Nikki Bhati who was set ablaze by her husband and in-laws in Greater Noida after demands for ₹36 lakh last week; 22-year-old Komal, newly married and pregnant, who was found dead in Delhi on August 21 over dowry demands; a woman from Aligarh, married for 10 years died in June after a hot iron was pressed against her body; another in Pilibhit burned alive for failing to appease her husband’s family dowry demands.

NCRB data shows that in 2022 alone, 6,450 cases of dowry deaths were recorded across the country, a figure that has barely shifted in five years despite the practice being outlawed more than six decades ago.

Last month, in July, a young bride in Chandigarh committed suicide after what her family described as relentless dowry harassment; in June, Logeshwari, four days into her marriage near Ponneri, Tamil Nadu, was gone, her in-laws had reportedly demanded more gold and an air-conditioner. Later that month in Tiruppur, another bride ended her life within two months of marriage, despite her family having already parted with 100 sovereigns of gold and a ₹70 lakh Volvo.

Each case lays bare the cruelty of dowry: whether four days into a marriage or ten years on, whether a woman is pregnant or raising young children, the demands strip away any trace of humanity. Dressed up as tradition, it remains a practice that turns homes into sites of extortion and violence while the law trails far behind.

From stridhan to extortion

Dowry in India did not begin as a weapon of violence. In its earliest form, during the Vedic period, it was known as stridhan, meaning ‘a woman’s wealth’. Gold ornaments, cattle, silks, or coins were handed to a bride as her personal dowry, meant to stay with her through life, serving as a small bulwark of financial independence at a time when land and inheritance were often out of her reach.

Over centuries, that logic shifted. By the medieval era, as caste hierarchies deepened, marriages became negotiations of status. Dowry was no longer simply a bride’s safeguard; rather, it became a ticket to a “better” match. Land, jewellery, animals, and even entire estates were transferred, transforming weddings into transactions where women were collateral.

Colonial law hardened this. British codification of inheritance largely excluded women from property rights, making dowry the only form of wealth they could expect. At the same time, the rise of salaried jobs under the Raj, that is, civil servants, officers, and clerks, put a price on grooms. A government posting could command an extravagant dowry, and with it, a lucrative marriage market was born.

By the time India became independent, the practice had metastasised into something darker. What was once framed as protection for women had turned into a lever of control against them. One of the earliest well-documented dowry killings occurred on 15 May 1979 in Model Town, North Delhi. Tarvinder Kaur, a Sikh bride, was attacked in her home: her mother-in-law doused her with kerosene and her sister-in-law set her on fire.

Before Tarvinder Kaur’s case made headlines, many dowry deaths were routinely categorised as accidents, often blamed on faulty kerosene stoves or ascribed to suicidal behaviour. There is little official documentation of dowry-based violence before the late 1970s, largely because such incidents were routinely misclassified and the law offered no specific framework to capture them.

Women’s groups, social reformers and a handful of parliamentarians began demanding legal intervention, arguing that the practice had morphed from a voluntary gift into a form of institutionalised extortion. The idea was also tied to Nehruvian nation-building: if India was to modernise, practices seen as feudal and regressive had to be dismantled.

In 1959, a private member’s bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha, sparking heated debates on whether criminalisation was even possible given dowry’s deep cultural roots. Two years later, the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, was passed, making both giving and taking dowry an offence.

The limits of the law

But the legislation was riddled with compromises: punishments were weak, reporting mechanisms were unclear, and enforcement was left largely to state machinery already reluctant to enter the domain of the family. What was meant to be a watershed moment ended up as a gesture, historic, but hollow.

It defined dowry narrowly as money or property given at the time of marriage, ignoring the reality that most demands arise later, once a woman is in her husband’s household. Families disguised transactions as “gifts”, police dismissed complaints as private squabbles, and the penalties, six months in jail or a fine of ₹5,000, were hardly a deterrent.

For women, the burden of proof was crushing: they had to establish there was a demand for ‘dowry’.

Of the 7,000 dowry deaths reported every year on average, only around 4,500 were charge-sheeted by the police. The rest were either stuck at various stages of investigation or disposed of for various reasons, including ‘case true but insufficient evidence’, ‘false case’, and ‘complaint was based on a misunderstanding or incorrect information’.

In 1983, Parliament added Section 498A to the Indian Penal Code, criminalising cruelty by husbands and in-laws. In 1986, Section 304B created the offence of ‘dowry death’, shifting the burden of proof to the husband’s family if a bride died unnaturally within seven years of marriage. These were hard-won changes, an acknowledgement that the 1961 law was too timid for the scale of violence it claimed to address.

In 2005, the state widened its lens with the Domestic Violence Act, which recognised dowry harassment as part of a broader spectrum of abuse, emotional, economic, and physical. The 2005 amendments sought to tighten the net. The definition of ‘dowry’ was broadened, penalties stiffened, and, controversially, the law criminalised not only those who demanded or accepted dowry but also those who gave it. The reasoning was neat in theory: shut off the supply by punishing both sides.

The paradox of punishing the giver

In practice, it has had the opposite effect. Families who pay dowry rarely do so willingly; they are coerced into it, fearing social stigma or violence. Now, if they report harassment, they risk incriminating themselves. Instead of emboldening victims, the law silences them. Courts, wary of “misuse”, push the burden of proof onto women already on precarious ground. Police dismiss harassment as “domestic disputes”. Conviction rates hover in the single digits.

Of the 7,000 dowry deaths reported every year on average, only around 4,500 were charge-sheeted by the police. The rest were either stuck at various stages of investigation or disposed of for various reasons, including ‘case true but insufficient evidence’, ‘false case’, and ‘complaint was based on a misunderstanding or incorrect information’. Some cases were stuck in the investigation stage for more than six months. Of the nearly 3,000 dowry deaths cases pending investigation at the end of 2022, 67% were stuck in that stage for over six months.

Of the average of 6,500 cases sent for trial every year, only around 100 resulted in convictions. Over 90% of the rest remained pending in court at various stages. If we look at the rest, some ended in acquittals, some cases were discharged before trial, and some were quashed.

Meanwhile, the concept of dowry has mutated in modern India. It is no longer just gold, cars, or cash handed over at the wedding. It is the wedding itself: the extravagant venues, the designer trousseau, the destination ceremonies broadcast on Instagram. It is the honeymoon abroad, the luxury apartments “gifted” by the bride’s family, the expectation that her parents will underwrite cars, holidays, or the couple’s lifestyle long after the marriage. What was once a social evil has been repackaged as aspirational consumerism.

Demands arrive dressed up as “customs” or “gifts”: gold at Diwali, an air-conditioner in summer, cash for a new business. When unmet, they spiral into cruelty and violence.

At the heart of the current debate is Tellmy Jolly v. Union of India & Ors, a petition before the Supreme Court that poses an urgent question: can the family of a bride, often operating under duress, humiliation, and threat, really be equated with the groom’s family, who demand and profit from dowry? The petitioner argues that, in punishing givers, the law criminalises the very people it ought to shield. Parents who cave in to demands to protect their daughter from harassment, or to preserve her standing in her marital home, are being recast as offenders instead of victims.

Section 3 of the 1961 Act makes the giver of dowry punishable at par with the taker. In theory, this bilateral criminality was meant to preclude collusion and break the transactional logic of dowry. In practice, it has bred a paradox: the very families who capitulate under social coercion, fearing ostracism or harm to their daughters, are cast as offenders.

Courts have long recognised this contradiction. While the statutory text admits no distinction, the judiciary has often displayed interpretive leniency, treating dowry givers as reluctant participants or even complainants. Prosecutions of givers are vanishingly rare. Yet the formal possibility of liability persists, producing both confusion and a subtle intimidation that deters some families from approaching the police at all.

It is this fraught ambiguity that the Tellmy Jolly case seeks to resolve.

Lessons from elsewhere

India is not unique in grappling with this dilemma. Bangladesh criminalises both giving and taking, mirroring India’s statutory symmetry. Nepal has gone further, instituting blanket prohibitions with criminal sanctions on either side. Pakistan has circumscribed the permissible value of wedding gifts, again penalising both givers and takers who transgress.

In contrast, the United Kingdom and most Western jurisdictions have no bespoke dowry statutes. Instead, dowry-like coercion is subsumed within broader frameworks of domestic abuse, forced marriage, coercive control, or fraud. Crucially, the law there is calibrated to protect the coerced rather than prosecute them. This divergence highlights the extent to which Indian law, in its current form, risks conflating the coerced with the coercer.

However, the critics of reform warn that removing penalties for dowry givers carries its own dangers. Without legal consequences, they argue, families may collude in the transaction, normalising the very system the law set out to dismantle. Wealthy households could continue to flaunt ostentatious dowries—cars, property, lavish cash transfers—under the guise of “voluntary gifts”, fuelling a culture of competitive display that leaves poorer families crushed under debt.

In this telling, the dowry system is not just enforced by those who demand, but also sustained by those willing to pay. To exempt givers entirely, sceptics caution, is to risk entrenching dowry as a socially sanctioned form of wealth transfer dressed up as tradition. The law, they insist, must find a way to protect victims of coercion without opening the floodgates to collusion.

What needs to change

The legal system has dismally failed to understand the situation of a woman’s extreme vulnerability in a patrilocal marriage where she moves to her matrimonial home and is isolated from her natal family, friends, acquaintances, or other support networks. She may be continuously monitored, and all her activities are controlled by the abusers who enjoy power and authority over her. A woman, alone in her matrimonial home, is continuously being taunted, humiliated, threatened, intimidated, dehumanised, and violated not only by her husband, but also by his other family members who join in to inflict abuse on her to forcibly coerce her to get dowry. And a few are being brutally murdered, or some are forcibly compelled to commit suicide in a state of absolute helplessness. In all such cases, the financial abuse extends not only to extorting money from the wives’ natal families but also includes the denial of women’s access and agency to money

For laws to work, they must reflect women’s realities. That means removing the liability of coerced givers, expanding the definition of dowry beyond the wedding day to cover post-marriage demands, and setting clear limits on wedding extravagance, as Kerala’s Women’s Commission has proposed. It means shifting the burden of enforcement from isolated women to state institutions, with special courts, faster trials, and police trained to treat complaints as crimes, not “domestic disputes”.

Reform means shifting the burden of enforcement from isolated women to state institutions, with special courts, faster trials, and police trained to treat complaints as crimes, not “domestic disputes”.

The Kerala State Women’s Commission in August 2021 submitted a draft bill titled ‘Prevention of Extravaganza and Unlimited Expenditure on Marriages in Kerala, 2021’ before the state government to check dowry harassment and ostentatious wedding celebrations, which impose a huge burden on the bride’s family. The Commission suggested amendments to the Dowry Prohibition Act because the state has reported several deaths due to dowry. From 2016 to June 2022, as many as 21,026 cases of dowry harassment and 84 cases of dowry deaths were registered in Kerala, and convictions were made in merely 251 cases.

The proposal set the maximum limit on the values of gifts given to the bride by her parents at Rs 1 lakh and ten sovereign gold. Additionally, the idea of mandatory pre-marital counselling for the bride and the groom is suggested in the said proposal. It also limits the value of gifts given by relatives to a maximum of Rs 25,000 and considers the bride to be the sole owner of the gifts. Such lawful measures at the national level may help to restrict the practice of checking dowry-related exploitation, aggravated harassment, and coercion, and more importantly, may help to reduce the burden on the bride’s family to incur expenditure on ostentatious wedding celebrations. Vital is the political will to enforce solutions to end harassment and brutal oppression of women.

Equally, reform requires political will—to cap the luxury marriage market, to regulate “gifts” that mask dowry, and to address the cultural complicity that sustains this economy of violence.

About the author(s)

Vanita is a lawyer by training and writes stories at the intersection of business & public policy, law, regulations and building inclusive workplaces. She is a Staff Writer for The Ken.

Comments:

Comments are closed.