The separation of powers is essential in any democracy. It is an integral oversight and accountability mechanism designed to curb abuses of power or institutional complicity in the event of such violations. However, as India’s democratic values erode under right-wing rule, are these accountability mechanisms beginning to buckle under the weight of a failing system?

On November 5, 2025, Rahul Gandhi made serious allegations of vote chori (theft) in Haryana during last year’s assembly elections. Accusing the BJP (which is currently in power in the state) of systemic election fraud in collusion with the Election Commission of India, Gandhi alleged that over 25 lakh fake voters were created in the state to ensure a BJP victory. He noted instances of duplicate entries and manipulated photographs. Gandhi has made a plethora of accusations, including illegal deletions, duplicate voter registrations, the use of fake addresses, bulk registrations at a single address, and the use of invalid photographs, not just in Haryana but across various states.

In January 2025, Gandhi alleged that fake voters were on the Maharashtra electoral rolls. In August 2025, he alleged voter fraud had occurred in the Mahadevpura Assembly constituency the previous year. Amid the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) exercise in Bihar this year, Gandhi had made similar allegations of fraudulent voters being registered in the state and of mass deletions of legitimate voters from the rolls. Whatever side of the political spectrum one falls on, it should go without saying that in a democracy, such grave allegations of election fraud merit a thorough and impartial investigation, at the very least.

Other allegations made by Gandhi

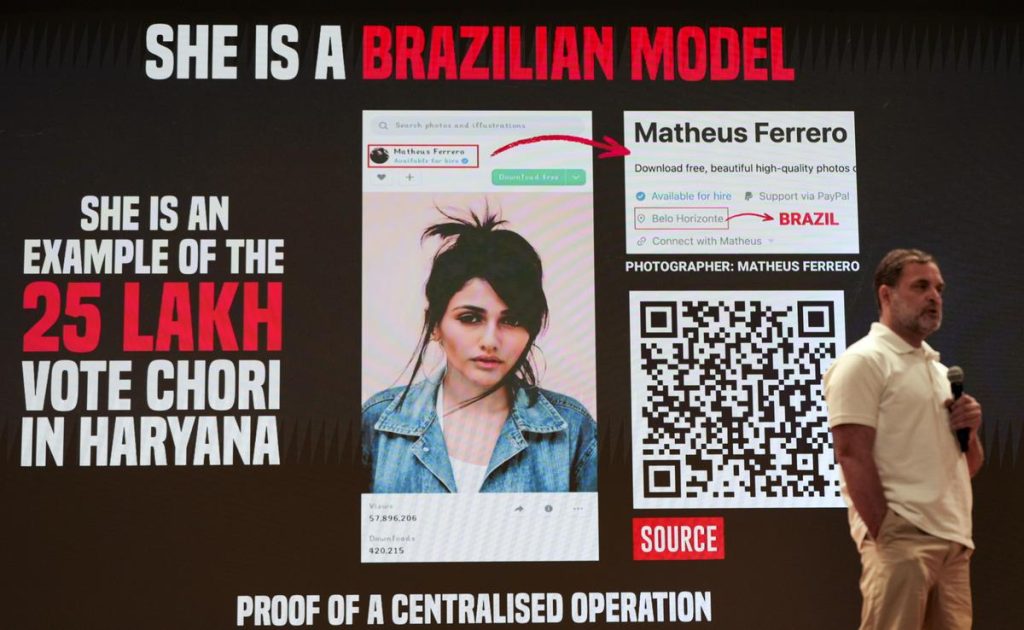

One instance of discrepancy mentioned by Gandhi during the 2024 Haryana election involved 223 people on the electoral rolls with the same woman’s image. In another example, he noted, a Brazilian woman’s stock images were also used in the rolls for 22 voters across 10 polling booths. As for the former claim, an Indian Express report found that this issue has long existed in that particular constituency. While people seem to possess Voter IDs with their correct photographs, their picture in the voter rolls is of the same woman, and this issue hasn’t been resolved following numerous complaints.

An independent investigation carried out by NDTV in Haryana’s Rai constituency, where the photo of the Brazilian woman appeared, found that several voters had inexplicably been removed from the rolls. Highlighting the cases of four families, NDTV found that the names of some or all members were missing from the rolls.

An India Today report alleged that while some instances of the Brazilian woman’s photos being used were a simple case of misprint, but found other discrepancies. In one instance, it was found that the details that appeared alongside the Brazilian woman’s photograph belonged to a woman named Bimla, who, unbeknownst to her, had two EPIC numbers associated with her details. In another instance, a woman who passed away in 2022 remained on the voter list, with her real details listed alongside a stock image.

In Maharashtra, the Congress alleged that more voters were enrolled than the state’s adult population. The party also claimed that the ECI had enrolled 50 lakh voters in the four months preceding the election. The ECI denied this claim. In a separate instance, a village in Maharashtra sought permission to hold a mock election following the December 2024 Assembly Election. The villagers claimed the election results from their village, which favoured the local BJP candidate, did not reflect how they voted. The village, which has long voted for Uttamrao Jankar of NCP (SP), and claims to have done so even in this election, was surprised at the results. The authorities denied permission for the mock elections.

Many legitimate voters were also removed from the Bihar rolls following the SIR, making people who voted in the 2024 general election ineligible to vote in the assembly elections. Gandhi had also made allegations of illegal voter deletions in Karnataka’s Aland constituency, ahead of the state’s 2023 polls. A Special Investigation Team (SIT) formed by the Karnataka Police investigating these claims raided former Aland BJP MLA, Subhash Guttedar’s house and found footage that showed his associates burning voter lists in his possession before the raid. Guttedar denied any wrongdoing.

The SIT also found evidence of efforts to manipulate voters’ lists outside of Aland. It found that a data centre in Kalaburagi was used to submit illegal online applications for voter deletions in Aland, at a fee of INR 80 per fraudulent deletion. However, it also uncovered that this data centre might have been used to manipulate voter lists in other constituencies. The Indian Express reported that it was primarily local BJP leaders who approached the data centre for its services.

Lack of Institutional Accountability

Apart from questions about political corruption, Gandhi’s allegations have cast a long shadow on the credibility of the Election Commission of India (ECI). Whether the ECI is colluding with the BJP or if the discrepancies highlighted by Gandhi are bureaucratic failures, the ECI still has a lot of explaining to do. Even if there was no collusion and the ECI has merely failed to accurately enter and update voter information, that still leaves room for denying people their right to vote and for voter manipulation.

However, the ECI has been on the defensive since Gandhi’s allegations, evading key questions and refusing to implement reforms to increase transparency and accountability. In August, when Gandhi alleged vote theft and demanded greater transparency in the process, including making election booth footage available to opposition parties, the Election Commission rejected the suggestion, arguing that doing so would threaten women’s privacy. However, the Reporters’ Collective found that the ECI, contradicting its position regarding voter privacy, had shared sensitive voter information with the Telangana government, which used it to develop its facial recognition software.

The ECI also doesn’t publicly provide machine-readable voter rolls. Which is to say, these voter rolls, containing crores of names, need to be manually read and scrutinised and cannot be read or analysed for discrepancies by computers. Machine-readable election rolls will allow for greater scrutiny and are an excellent transparency measure. The Congress had made a similar demand in 2018, which the ECI, backed by the Supreme Court, had denied. Following the Bihar SIR, it was reported that the draft rolls made available were mostly machine-readable and searchable. However, after Gandhi accused the rolls of being manipulated, the file was replaced with a larger one that AI tools could no longer read.

In October 2025, a lawyer filed a PIL before the Supreme Court, urging the Court to pass an order directing the formation of a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to investigate Gandhi’s vote theft allegations. However, the Supreme Court refused, stating that the petitioner could pursue the matter before the ECI. The petitioner had also requested the Court to direct the ECI to print electoral rolls in machine-readable formats. While the Election Commission is an autonomous body, India’s Constitution provides oversight mechanisms.

Speaking to FII, Akshara Rajratnam, a Lucknow-based lawyer who practices at the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad High Court, said, “The reason why the Supreme Court refused to order to formation of an SIT for investigation was due to a lack of strong and prima facie evidence showing failure of ECI in performing its duty. The ECI is an autonomous body, but that does not make it free from judicial scrutiny. Our Constitution, under Articles 32 and 142, empowers the court to order investigations even for cases involving independent entities, but only where fundamental rights are violated or the given evidence can make a prima facie case of the integrity of fair elections (which are part of the basic structure principle) being compromised. The courts avoid entering the thickets of politics, ordering investigations without the presence of such strong evidence risks the judiciary becoming the arbiter of political claims.”

The ECI hearing allegations against itself violates a core principle of natural justice: no one must be the judge in their own cause. Asked about what provisions exist to prevent the violation of this rule, Rajratnam clarifies, “There are various mechanisms, like external oversight, third-party investigations, or appointment of amicus curiae, where the court can order the investigation through a neutral authority, to ensure the principle of natural justice. The direction to complain to ECI does not indicate closure of the door; it simply preserves the procedural discipline. If the parties find the decision of ECI to be inadequate or compromised, the doors of courts are still open, and they can approach the court once again to seek redressal of their grievances.“

While procedural rules might bind the Supreme Court, the ECI is duty-bound to answer Gandhi’s questions and respond to his calls for more transparency in the process. The ECI’s position as an autonomous body doesn’t just afford it independence – within reason – from judicial intervention. It also gives it such freedom from executive intervention, something the ECI can no longer be said to enjoy with certainty. India has 96.88 crore registered voters, all of whom the ECI has a duty towards.

It wasn’t just the ECI that didn’t consider Gandhi’s allegations with the seriousness they deserve. Indian media, for the most part, uncritically parroted the government’s talking points. Very few media houses went through the trouble of investigating these claims or even reporting on them from a neutral perspective.

Gandhi’s allegations merit an investigation

While some of the things the Congress has based its claims on, such as exit poll predictions, might not be robust proof of voter manipulation, the party’s claims and the evidence provided, on the whole, at least warrant a fair, third-party investigation. If Gandhi’s allegations are untrue, as the BJP, ECI, and much of the Indian media claim, an independent investigation will reveal that. However, if there is any truth in what Gandhi has claimed and it’s overlooked, India’s democracy is at risk.

The country has nothing to lose by investigating Gandhi’s allegations, but everything to lose by shunning them without regard for their potential truthfulness. The choice, then, should be simple, but over a decade of Hindutva rule seems to have made what should have been simple math much more complex. India is the largest democracy in the world. Time and time again, everyone from our politicians to the public proudly reiterates this fact. Yet, in a truly democratic country, are serious allegations of election rigging a footnote, something to quickly deny on social media and prime time news and then move on from?

Free and fair elections are the source of all power in a democracy. The citizenry holds any control over their representatives only so long as they can cast their votes freely. Whether Rahul Gandhi’s allegations are factual or not is for our institutions to find out. However, if their autonomy from the executive is mired in doubt, it leaves Indians with few avenues to protect their democratic rights.

About the author(s)