At the British Museum, we find the Burney Relief, which stands in quiet defiance and presents a striking figure. It is a depiction of a winged woman that has talon-like feet standing alongside owls and a lion. Her name changes across traditions as she appears under different identities: Lilith, Inanna, goddess, demon, or a forgotten queen. Her presence feels ancient, hinting to us that the feminine divine once both helped creation and destruction, knowledge and wrath.

Patriarchal mythmaking has shaped the narrative we have of her by turning her complexity into danger. What happens when feminine divinity stops being contained and speaks openly again? This is a story of erasure and reclamation where figures like Lilith, Inanna, and Durga were erased and then reclaimed over centuries of faith, fear, and rediscovery.

Lilith and the politics of demonisation

In Jewish texts, Lilith is said to be Adam’s first wife, made from the same clay as him. Unlike Eve, she refused to submit to Adam and insisted on being his equal. It is said that when Adam asked her to submit, she spoke the secret name of God and fled Eden. Similar to her departure from Eden, Lilith disappeared from sacred history, which ended up further shaping the narrative we have of her.

In other mythologies, Lilith’s persona is somewhat demonised, as if her very independence was a curse that ended up shaping her story. She became a night demon, blamed for stealing children and seducing men. The same wings that once symbolised freedom were now a symbol of evil.

But feminist theology has begun to reclaim her. In The Coming of Lilith (1972), scholar Judith Plaskow reimagines her not as a demon but as a woman cast out for her autonomy. In Plaskow’s retelling, Eve eventually leaves the Garden of Eden, which becomes a radical act of sisterhood that turns exile into liberation. Plaskow writes, ‘They taught each other many things, and told each other stories, and laughed together, and cried, over and over, till the bond of sisterhood grew between them.‘

For many women, Lilith has come to be a symbol of resistance to oppressive systems that try to silence and punish female power, meaning the very divine feminine. Lilith appears in feminist rituals and contemporary media, where autonomy once condemned can be sacred.

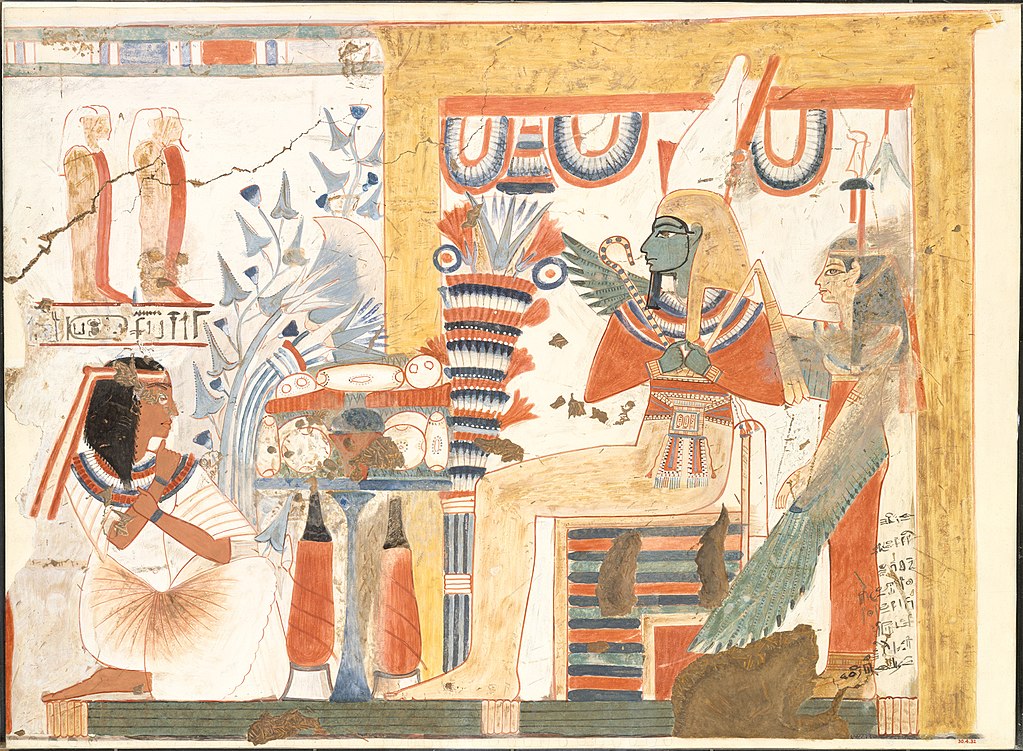

Goddess Inanna: descent as authority

Long before the Biblical tradition, the Sumerian Goddess Inanna ruled as Queen of Heaven and Earth, known for her power, beauty, and emotional depth. Her stories that are preserved in ancient cuneiform tablets show us a goddess who defies simple categorisation; Inanna is a warrior, a lover, a destroyer, and a nurturer all at once.

In The Descent of Inanna, as translated by Wolkstein and Kramer, she chooses to descend into the underworld voluntarily. When Inanna passes through the seven gates, she is stripped of her crown, jewels, and garments, the very things that symbolise her divine authority. Inanna’s death and eventual resurrection are not about purification but a rebuilding as she returns with deeper knowledge of death and the world underneath.

Over time, her complexity almost faded. The Babylonian Ishtar, who was derived from Inanna, became mainly associated with lust and war, and her deep spiritual layers were reduced to an archetype. The scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky explains to us in her work that as ancient religious systems shifted towards more male-dominated pantheons, powerful goddesses were reinterpreted or “domesticated” into narrower roles centered on fertility, eroticism, or conflict. Yet Inanna’s descent today remains compelling, as for many readers, this becomes an allegory about reclaiming power through vulnerability. In contemporary feminist narratives, Inanna stands for transformation without shame: a goddess who enters the dark and returns whole.

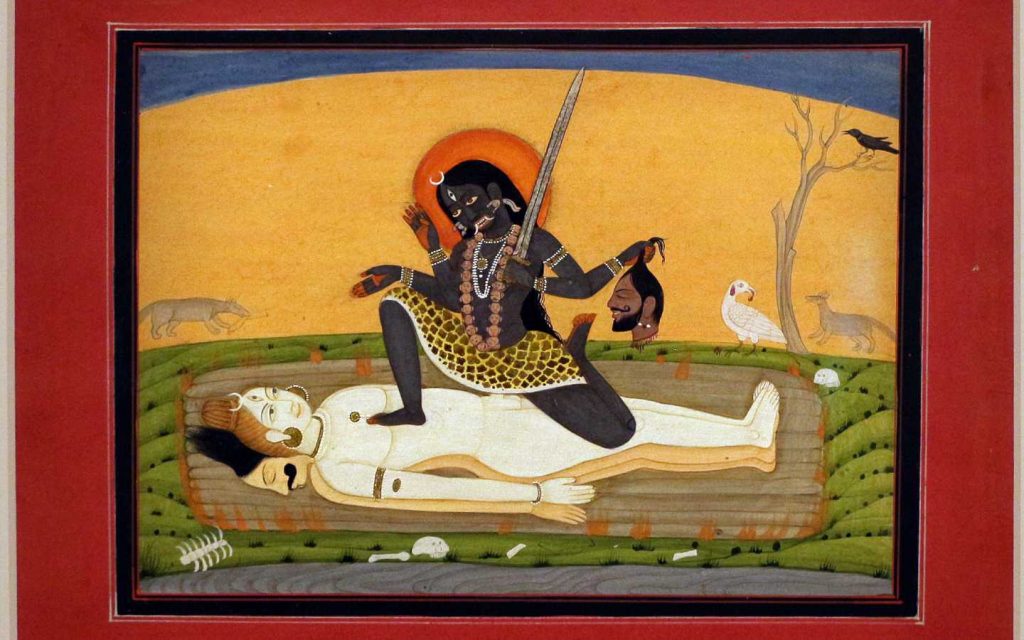

Kali and the politics of fear

Kali, whose very name comes from the Sanskrit kāla, a word linked to both time and black, represents the powerful and transformative side of the feminine divine. In the Devi Mahatmya, she emerges to defeat the demon Raktabija, whose blood, if spilled, would create endless clones. Kali drinks his blood before it hits the ground, destroying him and restoring cosmic balance.

Her story shows us that destruction, when used with awareness, is sacred and also necessary for renewal. Her appearance is as striking as her very myth. She appears with dark skin, wild hair, multiple arms, a necklace of severed heads, and a skirt of arms. She is both terrifying and captivating, and shows us that destruction is often necessary for creation. Historically, she has been worshipped outside the mainstream while being associated with cremation grounds, tantric rituals, and uncontrollable forces of nature.

Over time, she came to be worshipped as Kali Ma, a protective mother figure who is central to festivals like Kali Puja. And yet her uncontrollable power remains, refusing to be domesticated or softened. Modern feminist reinterpretation reclaims Kali as a symbol of autonomy and resistance. She serves as a reminder that neither the divine feminine nor women have to be passive or softened. This reclamation serves as a reminder that difficult forms of power are still sacred.

Why reclaiming matters today

Across different cultures, we see that goddesses are reappearing not just in temples or holy texts but can also be found in various forms of art, literature, and activism. In feminist practices and rituals today, Lilith is called upon as a symbol of equality. In Wiccan and Neopagan practices, Inanna’s descent is performed as a personal rite of transformation. In India, Durga and Kali often appear in contemporary art and campaigns to symbolise women’s power and resistance.

To reclaim these figures is not just about reviving mythology but rewriting memory. As theologian Carol P. Christ explains, when we imagine the earth as the body of the Goddess, ‘the radical implications of the image are more fully realized,‘ because this idea helps us see the natural world and women as sacred again, since both have been devalued and controlled for so long. Her insight shows why reclaiming matters today because recalling the divine feminine becomes a call to heal what has been harmed from women’s bodies to our very own planet.

Reclamation of these stories, however, does invite debate. Some critics argue that contemporary reinterpretation risks the distortion of the sacred texts and narratives. But mythology itself has always shifted over time as it survives through being retold and reimagined by every generation.

The Burney Relief’s winged woman still meets our gaze not as a demon or angel but as her own self. Her story, alongside those of Lilith, Inanna, and Kali, reminds us that the sacred once allowed women to hold many contradictions all at once and that too without apology. To be nurturing and dangerous, tender and firm.

If goddesses once embodied both destruction and creation, why must women now struggle to be seen in all their complexity? Perhaps reimagining the divine feminine is less about making new myths but reclaiming the ones that were once pushed aside.

About the author(s)

Juhi Sanduja is an Editorial Intern at Feminism In India (FII). She is passionate about intersectional feminism, with a keen interest in documenting resistance, feminist histories, and questions of identity. She previously interned at the Centre of Policy Research and Governance (CPRG), Delhi, as a Research Intern. Currently studying English Literature and French, she is particularly interested in how feminist thought can inform public policy and drive social change.

Interesting paper but Lilith is NOT Inana, nor Ishtar and the Burney relief copied is NOT Lilith. READ Christophe STENER, Lilith, un mythe juif (Lilith a Jewish Myth) ISBN : 9782322581078 and notably the chapter about “Lilith, Icon of Feminism” 30 pages long