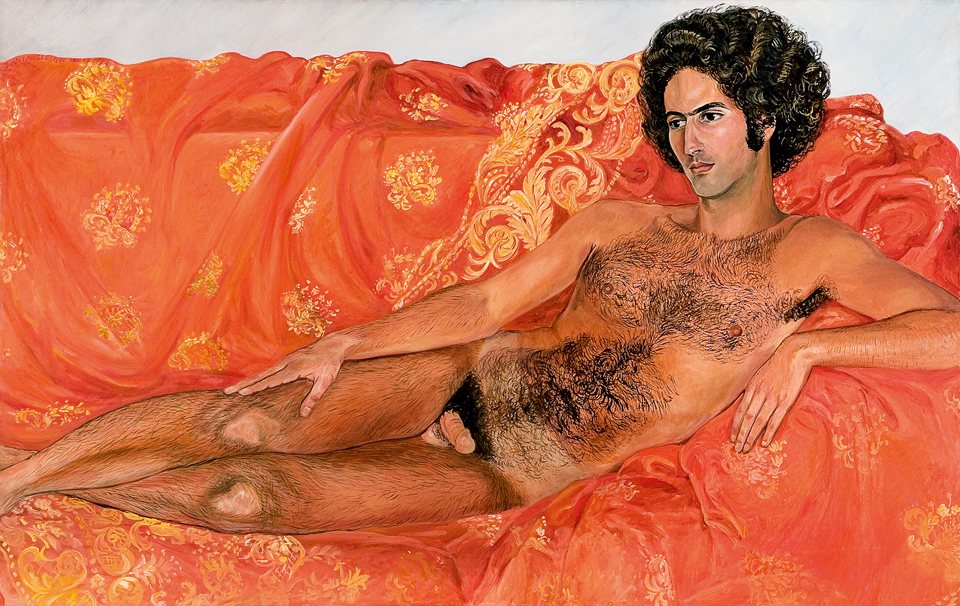

A few years ago, I visited a painting exhibition in Kolkata. The painter primarily focused on male bodyscapes. A viewer nearby muttered, ‘All I see are works focused on men.’ I turned to him and asked, ‘Would you feel the same if the artworks featured women? Would that thought cross your mind?‘ The gentleman smiled awkwardly with no response.

For centuries, art has taught us how to view women’s bodies. The female body has been painted, sculpted, photographed, and consumed countless times. It has served as a muse, mother, goddess, or victim, but rarely had its own agency. It seldom resists, speaks back, or unsettles those who look at it.

Performance art and Marina Abramović: when her body became an active medium

Performance art always tried to disrupt this long history of silence. Instead of treating the body as an image or specifically a tool, it uses it as an action. Performance transforms the act of watching. It emphasises that the body is not merely something to be seen – it acts, questions, confronts and protests.

Few artists demonstrate this change as strongly as Marina Abramović known as the “grandmother of performance art”. Abramović had a great impact on this particular genre where she used her own body: female, vulnerable, disciplined and tolerant, to question violence, power and the role of the people as viewers. Although her work began in a European context, its feminist message resonates deeply in third world countries as well, along with India, where women’s bodies and identities are also targets of suppression, moral policing, caste violence and political torture.

Bodies under surveillance

Born in 1946 in Yugoslavia Abramović grew up in a strict, authoritarian home. Her movements, time and presence were constantly monitored. Surveillance was a real experience for her. In her interviews, Marina always talks about her disciplinarian mother who was quite obviously shaped by the patriarchal system. This shaped her belief that the body is never neutral, rather it’s disciplined, regulated, influenced by the power dynamics a woman faces in everyday life.

This situation is all too familiar in India. There are restrictions on mobility and clothing, caste-based segregation and monitoring of women’s sexuality. Reproductive rights are also controlled. The body is key to how power is exercised. Performance art works as an important feminist tool because it shows this control in real visible body movement, not by any theory.

Rhythm 0: when violence is permitted

Abramović’s early performances completely rejected representation. She showed tolerance, violence and pain with her body directly. There was no question of symbolism – it made the audience active witnesses. This focus on the physical experience allows her work to connect with various cultures and situations and obviously certain mindsets.

Abramović’s early performances completely rejected representation. She showed tolerance, violence and pain with her body directly.

One of Abramović’s most unsettling pieces, Rhythm 0 (1974), is an important feminist statement. For six hours, she stood still while the audience could use any of 72 objects placed on a table on her body, including feathers, roses, knives & a loaded gun.

What happened next was a slow move from care to cruelty. Her clothes were cut, her skin was marked. Her safety was in jeopardy. The performance revealed a troubling truth: when a woman’s body is viewed as passive and “available,” violence is not an exception; it becomes “permissible.” Abramović described it later: ‘What I learned was that … if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you.’

In India, this way of thinking is quite familiar. Sexual violence justified by victim-blaming, public harassment framed as entitlement and caste-based abuse asserting dominance through physical harm, all function within the same social permissions. Rhythm 0 forces us to face a difficult question: is violence shaped by systems that normalise access to particular bodies or is it the product of individual deviance?

Similar questions have been raised by Indian performers as well. For instance, vulnerability, shame and endurance are explored in Sonia Khurana’s performance and video works, especially in relation to the discipline of female bodies in both public and private settings. Her practice, like Abramović’s, requires viewers to take responsibility.

Politics of beautiful presentation: Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975)

While reciting the title line of the 1975 performance, Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful, Abramović kept brushing her hair. The once-familiar act of personal grooming quickly turned into an aggressive and painful act. Instead of showing beauty as self-care, the show emphasises that beauty is a requirement for women. It affects their bodies and their identities.

While reciting the title line of the 1975 performance, Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful, Abramović kept brushing her hair.

Indian women artists often face tough expectations around cultural respect, modesty, and meeting aesthetic standards. This pressure weighs heavily on them. Performance art poses a challenge because it goes against these expectations. Unlike physical objects, it cannot be sold, stored, or easily displayed.

Artists like Mithu Sen use absurdity, language and the body to address issues of sexuality, propriety, and the policing of female expression. By avoiding seriousness, coherence or respectability, these practices challenge the standards of “acceptable” art and what it means to be a woman.

Endurance and labour: the politics of pain

A key component of Abramović’s work is endurance. Her art focuses on labour, especially the emotional and physical tasks women are often expected to do without appreciation. This is evident whether she is sitting silently for hours or pushing her body to its limits.

In India, people often view women’s perseverance through the lens of the selfless mother, the goddess figure, the devoted spouse, and, of course, the patient survivor. By highlighting endurance, uncomfortable and political performance art challenges this narrative.

Without offering neat answers, Tejal Shah’s performative video works examine queerness, ecology, and vulnerability.

Without offering neat answers, Tejal Shah’s performative video works examine queerness, ecology, and vulnerability. Lens based practitioner Sheba Chhachhi’s early feminist interventions in the 1980s addressed communalism, patriarchy & state violence through performance in protest spaces. Abramović’s assertion that pain is structural rather than just symbolic is echoed by these practices.

Presence as resistance: The Artist Is Present (2010)

The Artist Is Present (2010) by Abramović marked a shift from physical endurance to emotional vulnerability. She turned silence into confrontation by sitting quietly across from museum visitors – doing “nothing”, which became a daring act in a society fixated on display and productivity.

Indian women often hear the question, ‘Why are you here?‘ in public spaces. Simply being present can be a form of defiance. Occupying space without apology challenges deeply rooted social expectations.

Feminism and the othered ecology

When talking about suppression and endurance, we should acknowledge that ecology is just as important as feminist identity. Our mechanical society views nature and the environment in the same way it views women. Both are seen as things to exploit, tolerate, and push aside. Nature is treated as servile, expected to endure constant pressure and accept our demands.

In the subcontinental context, artist Mallika Das Sutar’s performance is particularly relevant. She combines her body movements with the natural world, becoming part of the environment in a community space. Her artistic expression breaks down barriers, making her body an essential part of the ecology.

Beyond institutions: performance in Indian public spaces

Much of feminist performance in India has taken place outside of elite art institutions. It happens in streets, protests and community spaces in our daily lives. From anti-caste movements to queer pride marches, these performances reclaim visibility and agency. They may not always be viewed as “art,” but they aim to disrupt, confront & resist erasure.

Abramović often resists being labeled a “feminist artist”. However, her work reflects feminist ideas through action rather than words. She does not provide solutions or moral clarity; instead, she exposes systems and leaves audiences feeling uncomfortable. She has consistently shown that artists have a responsibility to challenge oppression.

Feminist art, like any kind of subaltern art, is not meant to comfort. It is meant to ask tough questions.

This discomfort is important. Feminist art, like any kind of subaltern art, is not meant to comfort. It is meant to ask tough questions. Who is allowed to look? Who is allowed to touch? Who is believed? Who carries the burden of endurance?

Indian feminist performance practices challenge straightforward stories. They are complex, physical, and highly political. They dismiss the idea that respectability is necessary for legitimacy. Marina Abramović’s significance in India does not stem from imitation but from connection. Her work highlights that the body is both a battlefield and a means of expression, as Barbara Kruger once said. Vulnerability can be confrontational, and silence can be powerful.

For Indian women artists dealing with censorship, moral policing, caste systems, and diminishing public spaces, performance offers a way to communicate beyond traditional representation. It emphasises presence and calls for attention.

Abramović once said that the hardest thing to do is “nothing.” For women whose bodies are often talked over, controlled, or vanished, doing “nothing” by standing still and refusing expected roles can be the most radical act. Feminist art does not focus on idolising individuals; it highlights lineage, dialogue, and shared resistance. Placing Marina Abramović next to Indian women performance artists shows how feminist struggles change and fit into local settings. The body reacts and when it does, it changes both the way we talk about art and the politics of self-reflection.

References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marina_Abramovi%C4%87

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/oct/03/interview-marina-abramovic-performance-artist

- https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-40-summer-2017/interview-tehching-hsieh-marina-abramovic

- https://courses.mapacademy.io/topic/performance-art-conversations-with-body-and-space-2/

- https://imma.ie/collection/art-must-be-beautiful-artist-must-be-beautiful/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ginIp-GilM

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marina-Abramovic

- https://asapconnect.in/post/241/singlestories/sounding-the-future

- https://volte.art/artists/25-sheba-chhachhi/

- https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/964

- https://www.facebook.com/ngmadelhi/posts/live-performance-by-renowned-artist-mallika-sutar-at-ngma-kolkata-on-the-occasio/845005791185766/

- https://www.vogue.co.uk/arts-and-lifestyle/article/marina-abramovic-interview

About the author(s)

Subhajit Naskar is a Kolkata-based photojournalist and visual artist. Capturing the melange of emotions through the lens is his forte. The stream of human emotion has always moved him from the inside. He believes visual expressions are much more alluring than any other socio-psyche construct. To him, all frames are more than mere pictures; they narrate stories- stories of emotions. To him, photography is not just a hobby but a passion for politics, the portrayal of human life, and a mirror of emotions. He was recognized in the Toto Photography Awards (Finalist), Black and White Spider Photography Awards, Lensculture Street Photography Awards, Polyphony International Photo Festival, International Color Awards, Create COP26, Indian Photo Festival - Hyderabad, etc. His works have been published in Vice Media, The Quint, The Citizen, Himal Southasian, Gaon Connection, etc