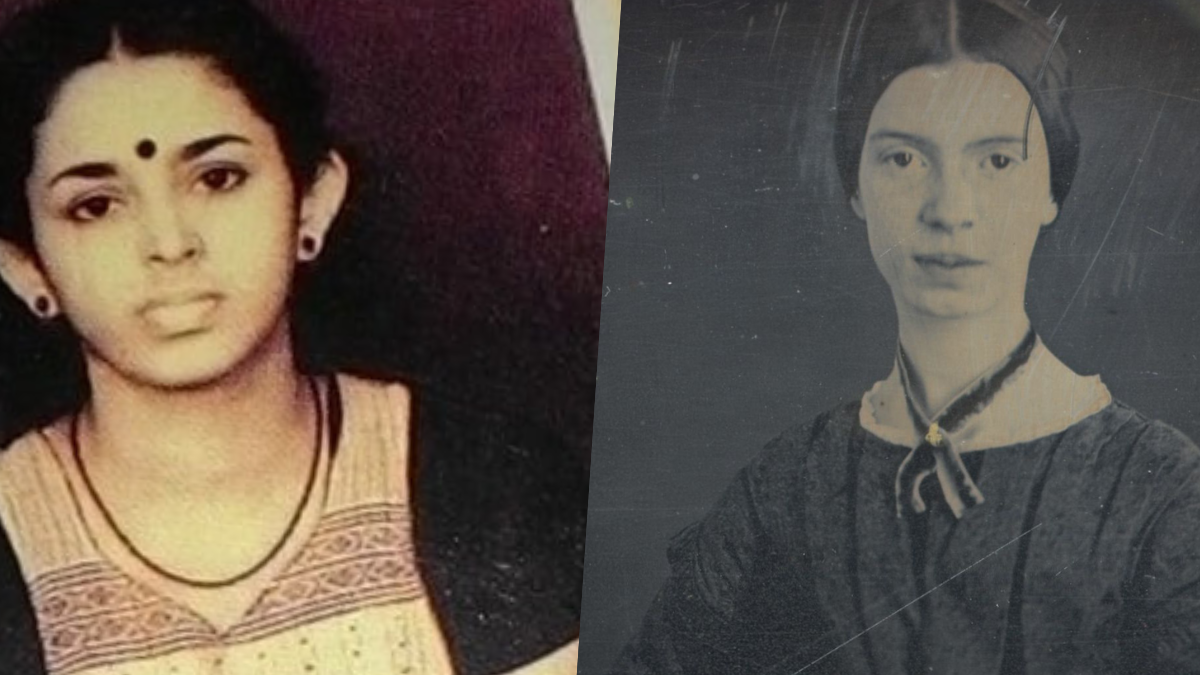

Nandita K.S, a poet born in the hilly Madakkimala village of Wayand,Kerala, who took her life at the age of twenty-nine, left behind a miscellany of poems that were discovered and published posthumously, much like Emily Dickinson’s belated accolade.

In Emily’s ‘Chariot of Death’, she passes through the ‘fields of gazing grain’, suggesting continuity of life’s cycles, possibly inspired by the topography of Amherst and the Connecticut River valley, where Emily lived. In a similar manner, in her desire to ‘sleep forever’ Nandita inhales ‘odour of thy abyss, to destroy the sense of helplessness’ with respect to night, contemplating death, suggesting a radical sensory yearning for the darkness to overpower human helplessness, possibly drawn from Nandita’s experiences related to the highland night skies over the Wayanad hills, where she grew up. It transcends spatial boundaries by making readers experience that such diverse landscapes can coexist in a parallel imaginative space, contoured by the allegory of death.

In spite of the inadequacy of established hierarchies, cultural capital disparities and power structures existing when comparing Nandita, a poet from the Global South, with Emily, this prose is a bold attempt to link Nandita with Emily for their posthumous recognition, in which death functions as an unsettling site of liberty from a world that was unsuccessful in hearing them while alive. There is an additional daring attempt to loosely translate Nandita’s Malayalam poems, mostly untitled, orphaned, wandering in digital spaces yet steadily confronting human alienation, love, longing, death, and despair.

Gendered literary visibility in which women’s voices are unheard is prevalent in non-

Western marginalized frameworks too. When Emily’s poetry is admired canonically,

Nandita’s poems are yet to receive justifiable credit. The rationale for this attempt is to

investigate how the appreciation they received posthumously exposes systemic indifference

and neglect and how women affirms agency through poetry even at the face of death.

Authority over Death

Death is never perceived by either Emily or Nandita as the culmination of worldly experiences or the grand finale of human life. It appears in their poems as a site of resistance where both of them resist against the conventional expectations and conditioning imposed by the traditional hierarchies they lived with, instead.

In Emily’s ‘I heard a fly buzz when I am died’, the posthumous voice of the protagonist gives

narrative authority that subverts conventional expectations about death as the end of human existence. As the narrator refuses emotional surrender in the face of death, consciously shifting the narrative to the mundane, a fly, messy and uncontrollable, to reconfigure death from the cultural expectations of spiritual submission, in front of the ‘King’ or death itself. The deceased narrator is probably a female voice, as she ignores pious narratives associated with death, drawn from the patriarchal expectations of society.

the extinguished fire in me being reborn;

the stench of charred scalp,

bones broken down to ashes and combusted tissue

a cackling skull.

staring at the hapless earth that desperately hides her infertility

I giggled, silly!

– Nandita.K.S

The imagery of death placed in the backdrop of Hindu cremation rites confirms that the narrator refuses to submit to death; she rather reclaims authority through incineration. The deliberate unconventional description of the burning body destabilises the spiritual expectations of death as a site of pious finality. The feminine earth, whose infertility is trivialised and laughed at, by the narrator, who is the dead person who holds the power to reconstruct the constraints of the living feminine.

Death as Empowerment to Resist Societal Obligations

A deserted battlefield

an uninhabited bivouac,

some ruined bangles,

trace of vanishing sindooram

the barren earth is savoring;

the love dispersed from the cracked earthen pot.

A smile plunged into the veil.

teary eyed,

a farewell, along the shades of the Saree.

When drenched in white,

love turns to the virtuous spouse;

Tulsi, the woman deceived by God himself;

succumbs without a rebirth.

Once again, I have been left alone.

– Nandita.K.S

The poem observes the battlefield of life, where war and love have collapsed, and where symbols of femininity and marriage have fallen. The last bit of remnant love that could not be contained was savoured by the barren earth. Death becomes defiance in the face of fragile social

structures. Even in the time of grief, the narrator regains agency over emotional display by placing a smile on the ceremonial female self. The conditioned emotion of widowhood ‘drenched in white’ is outplayed by the moral performance when the narrator places death as resistance to societal obligations. Through the metaphor of Tulsi, who was deceived by God, and by the denial of rebirth that stripped women of agency, death is reconstituted when the lone dead female stubbornly refuses to be reborn to be shaped by the obligatory patriarchal norms and customs.

For Emily, death purchases a room, escape from circumstances and a name in ‘For Death-or rather For the Things ‘twould buy’. Hailing from a period where rigid patriarchal and social constraints existed for women, death procures autonomy and space outside the obligations for the narrator. It redefines her name and identity. Death lets her escape from the circumstances of life’s womanly duties. The narrator asserts female agency to resist socio-cultural conditions, and death validates her in doing so.

Romantic longing for Death

Now I realize that

it means death to me to forget you.

As I am just you, only.

– Nandita.K.S

The lone lover, lost in Vrindavanam, in Nandita’s poem, encounters the in-betweenness of her emotional longing for her beloved and her rational resolve to get over him. Eventually, the narrator settles for the ultimate truth of her romantic longing as death itself, as she identifies herself with him spiritually. Death symbolises divine surrender to romantic desire. Death does not resemble an ending here, too; it is rather an eventual union with the beloved. The surrender is self-assertive and claims agency, embracing spiritual autonomy to the fullest.

Similarly, Emily embraces death as a ‘supple suitor’ who woos the narrator with subtle signals first and arrives bravely in triumph at last. The union with the beloved of the narrator is realised through death, and the spiritual surrender becomes an expression of agency.

Death certainly becomes a site of resistance against everything that left them unheard in their lives and in their poems. But it is unsettling that these bright, conscientious and perceptive women had to die for the world to be reminded that how death is contemplated in their poetry, compelling obstinate feminist readers to re-read and make humanity hear their forethought.

About the author(s)

Dr Parvathy Poornima teaches at St Joseph’s University, Bengaluru. Her research areas includediaspora studies and the experiences of South Asians in the United Kingdom. She holds a PhD from JNU.She’s a full-time mom who navigates her career and passion with perseverance.