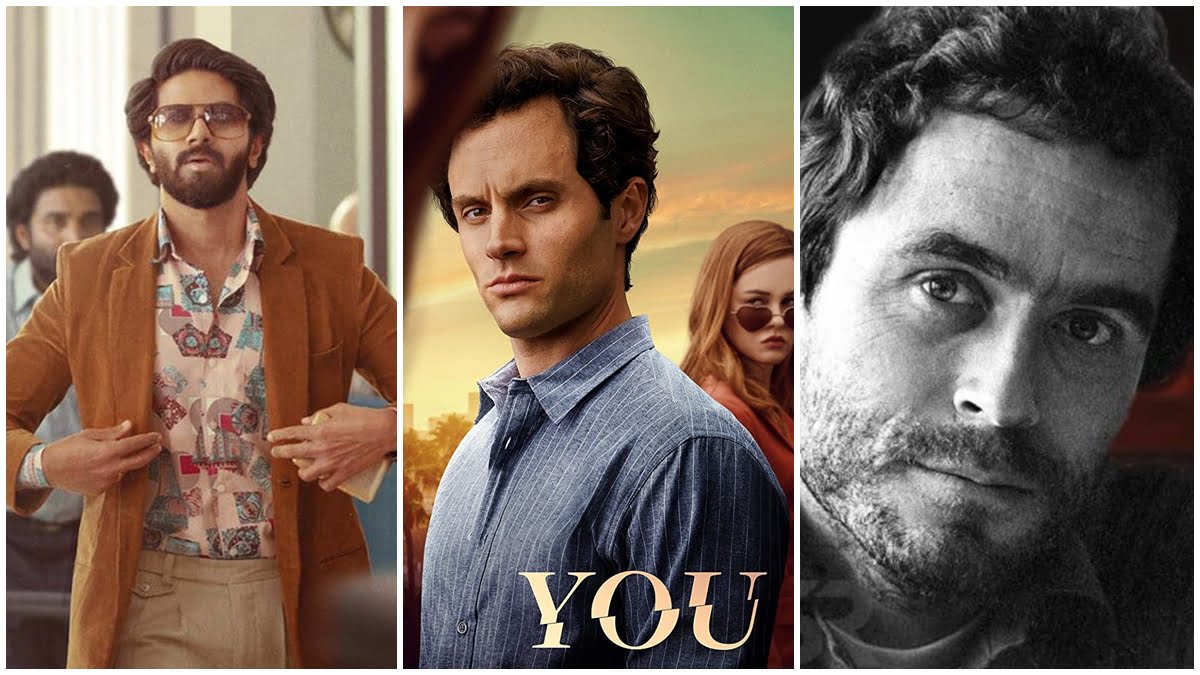

Recently, I saw a viral Instagram reel on Joe Goldberg, the friendly neighbourhood serial killer and the main character of Netflix’s popular series, You. The woman in the reel said “If my stalker is that hot, I don’t mind…”

I paused for a moment.

We have all had instances where we were scrolling through social media and saw posts about controversial couples, such as Harley Quinn and Joker, with a corny love caption. Most of us have been so desensitized to it that we don’t really see anything wrong with it anymore.

You, as a show, is a satire. It is an American psychological thriller series that asks a simple question, “What would you do for love?” The answer, however, isn’t that simple. You shows how society is willing to forgive people who are ‘privileged’ with a certain skin colour, gender, and look, and how much less willing to forgive people who don’t fit those boxes. The protagonist, Goldberg, has had a troubled past. However, let’s remember that history isn’t an excuse to inflict pain on other people. Furthermore, I see an open commentary on several societal and moral issues within it, from domestic violence, abuse, society’s vapidness and how we interact with social media today, as well as an interesting take on the dichotomy of good and evil. When you romanticize the exact thing the show tries to stand against, you neutralize the entire movement.

Also read: Decoding The ‘Charismatic’ Serial Killer Cinema Narrative

Society has molded us into believing that “good” relationships aren’t interesting. “Good” people are boring, and that’s why antiheroes are a big thing right now. There is an obsession with toxicity in romance. For some, the pull is instinctive. Empathy toys with your emotions. You see a wound and want to mend it, no matter the cost. It’s a test of endurance that you’ve grown to accept. How much hurt can you take? How much love can you give? Amidst these questions, happiness is a background thought, and you are colour-blind in a field of red flags.

Society has molded us into believing that “good” relationships aren’t interesting. “Good” people are boring, and that’s why antiheroes are a big thing right now. There is an obsession with toxicity in romance. For some, the pull is instinctive. Empathy toys with your emotions. You see a wound and want to mend it, no matter the cost. It’s a test of endurance that you’ve grown to accept. How much hurt can you take? How much love can you give? Amidst these questions, happiness is a background thought, and you stand indifferent in a field full of red flags.

There is a common notion that the more someone is willing to do for you, the more they love you. And these toxic romantic clichés need to be addressed. This fascination with psychopathic tendencies in relationships isn’t limited to television; it has crossed into the domain of documentaries. There are many documentaries about serial killers in which their motives and actions are analyzed. Recently, with the release of the Netflix documentary, Ted Bundy has become known for his looks more than his murderous deeds. It’s scary to see hundreds of people in online forums chatting about how attractive Ted Bundy or Richard Ramirez, a serial killer who terrorized Los Angeles and San Francisco in the mid-80’s, is.

Recently, with the release of the Netflix documentary, Ted Bundy has become known for his looks more than his murderous deeds. It’s scary to see hundreds of people in online forums chatting about how attractive Ted Bundy or Richard Ramirez, a serial killer who terrorized Los Angeles and San Francisco in the mid-80’s, is.

On the same lines, as Dulquer Salman’s film Kurup, based on one of the most wanted criminals of Kerala, Sukumara Kurup, is about to release, several concerns have been raised over how a romanticised portrayal of the fugitive is a disservice to the families who have suffered because of the murders Kurup committed.

The media portrays villains as sympathetic characters or protagonists because audiences are attracted to complexity. Watchers and readers long for an antagonist’s redemption but forget their crimes altogether when it appears.

When victims of abuse are wronged by a lover, they follow the same logic. If Padme could forgive Anakin for slaughtering the Jedi [Star Wars reference], surely I can look past a bruised ego or a split lip. They fall for the illusion of “fixing,” and convince themselves that in one more day, one more week, one more month, their abusers will change. Like Darth Vader, their love will conquer the Dark Side.

Also read: Dirty John Reveals How Society Helps Abusers Co-Opt The Victim Narrative

The sad reality is that there is no Dark Side. Abusers are cruel and deceitful and, most importantly, aware. Most human beings, whether they be a hero or a villain, have free will. They can consider their options, weigh wrongs and rights, and decide on a course of action. As an audience, when we choose to accept a romanticised portrayal, it by extension could be seen as abusers being made to feel free of any guilt they may or may not experience. We add to their repertoire of power while waiting for the antihero’s redemption arc, forgetting the injustice they have committed. The “protagonist” you see in the mirror becomes a background character, a strip of white-out on the script.

Social-media has romanticised the idea of romance and it’s dangerous. People are more in love with the idea of love than the person they are with. And when we mould generations in that world where love is the answer to everything, we allow their feelings to burn fiercely, consuming everything in sight only to dissipate and leave codependency or ruin in its wake.

Aishwarya Roy is pursuing her Master’s degree in Biotechnology. She reads a lot on science, history, and politics, and writes to make herself feel things. You can find her on Instagram.