“Issues of sexuality are intrinsically linked to caste and address of sexual politics without a challenge to Brahmanism results in lifestyle feminisms,” says Sharmila Rege.

“Many women become invalid for life and some even lose their lives by the birth of children in their deceased condition or in too rapid succession. Birth control is the only sovereign specific remedy that can do away with such calamities. Whenever a woman is disinclined to bear a child for any reason, whatsoever, she must be in a position to prevent conception and bringing forth progeny which should entirely be dependent on the choice of women.“

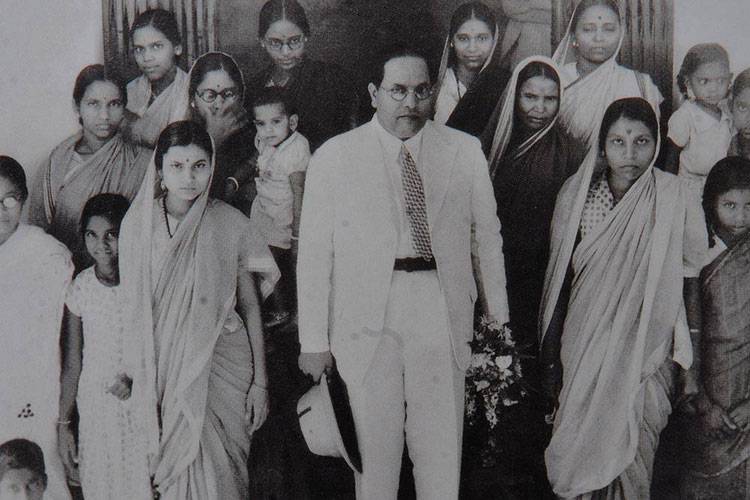

Dr. B R Ambedkar

It is impossible to talk about intersectional feminism and not mention Rege, an Ambedkarite- feminist practitioner. The aforementioned statement is an argument put forward in one of her essays, titled, “Dalit Women Talk Differently: A Critique of ‘Difference’ and Towards a Dalit Feminist Standpoint Position”. Sharmila Rege, a sociologist, feminist academic, and author, worked towards realizing the fact that gender and Dalit studies were inextricably intertwined.

Dalit women’s problems are different and distinctive in many respects because they bear the triple burden of economic hardship, patriarchy, and caste-and untouchability-based discrimination, which cannot be eliminated only by enforcing anti-discriminatory legislation. She believed that Ambedkar’s vision was influenced by conceptualising Indian modernity from a feminist standpoint. All of Ambedkar’s attempts were focused on creating a space for women where they were heard, including Dalit women.

Baba Saheb Ambedkar’s works and political reforms have largely been narrowly categorised as Dalit reforms, and his identity as a feminist activist and thinker has been ignored. This systematic marginalisation of his works is a direct consequence of the working of Savarna feminism. It is time we acknowledge his contribution in shaping feminism in India. His approach towards feminism was not only theoretical but pragmatic as well.

He pointed out the gendered violence meted out in Hindu texts, like Manusmriti. In a society whose demarcation of privilege is based on one’s caste, caste-based anxiety prevails in abundance. The anxiety to secure purity is conducted through policing the morality and sexuality of women. The woman’s body acts as the perpetrator of impurity, and therefore needs to be regulated through violence.

As Uma Chakravarty, in her essay Conceptualizing Brahmanical Patriarchy in Early India: Gender, Class, Caste, and State, writes, “The safeguarding of the caste structure is achieved through the highly restricted movement of women or even through female seclusion. Women are regarded as gateways—literally points of entrance into the caste system.” Ambedkar held the same view that the caste system lays out an edifice for women’s subjugation that was detrimental to the idea of equality. He saw exclusionary violence and female oppression as fundamental driving factors in the process of maintaining caste hierarchy.

Also read: Here Is Why Ambedkarites Refuse To Call Themselves Harijans And Dalits

Amidst the time of political turmoil, where the issues of women were overlooked, Ambedkar published Mooknayak and Bahiskrit Bharat where exclusive sections were committed in covering women-centric issues. In an attempt to give back to females their agency, he formulated the Mine Maternity Benefit Act which requested equal pay and equal participation of women in the coal mine workers’ welfare fund and emphasised equal citizenship and women’s right to economic growth as the crux of women’s rights in India.

Between the years 1942 and 1946, he also formulated various pro-women laws, including equal pay for equal labour, casual and privileged leave, injury compensation, and pension. As a member of the Bombay Legislative Council in 1928, Ambedkar voted in favor of a measure guaranteeing paid maternity leave to factory workers. According to him, it was the duty of the employer to ensure the women’s financial safety during their maternity leave as they profited from their labor. With this act, he demonstrated both class and gender consciousness by focusing on the economic and productive aspects of motherhood among working-class women.

Ambedkar examines Rama’s behaviors through the prism of social philosophy and concludes that they are not only inequitable to a woman but also profoundly immoral. Rama was portrayed to be the hero ignoring Sita’s subjectivity and individuality throughout the epic. As a result, he rejects the Ramayana as a guiding principle of an ideal way of life since it advocates the slavery of women in the institution of marriage, which contradicts his concept of social justice.

Abortion still remains a topic of taboo. Countries across the globe, today, are fighting for abortion and reclaiming the autonomy of their body. Hence, it can be imagined how abortion could have been viewed several years ago. However, Ambedkar talked extensively about the control of women over their own bodies. It was the time when patriots, revolutionists, and eminent writers were motivated by the idea of India as a mother.

Also read: Public Universities: The Site For An Emerging Ambedkarite Struggle

From Bankim Chandra’s Vande Mataram (Hail to the Mother), Bipin Chandra Pal’s renditions, to Abanindranath Tagore’s famous painting of Bharat Mata, glorified motherhood and reproduction as a means of nation building. Amidst such a volatile political scenario, Ambedkar, in 1938, as a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly, said, “ If men had to bear the pangs which women undergo during childbirth, none of them would ever consent to bear more than a single child in his life.” He further argued, “Many women become invalid for life and some even lose their lives by the birth of children in their deceased condition or in too rapid succession. Birth control is the only sovereign specific remedy that can do away with such calamities. Whenever a woman is disinclined to bear a child for any reason, whatsoever, she must be in a position to prevent conception and bringing forth progeny which should entirely be dependent on the choice of women.”

His attempts towards giving women their voice were not only restricted to his writings or words, movements led by Ambedkar were women-inclusive. He declared, “I strongly believe in the movements run by women. If they are truly taken into confidence, they may change the present picture of a society that is very miserable. In the past, they have played a significant role in improving the condition of weaker sections and classes.” Mahad Satyagraha, which was aimed at breaking the law of not allowing the members of the Mahar community to drink water, witnessed about 10,000 men and women participating. Ambedkar urged women to break out of their social domains and voice their muted opinions during the Kalaram temple-entry movement.

The Hindu Code Bill was, perhaps, the most important step taken by Ambedkar toward the vindication of women’s rights. This Bill was intended to define property rights for men and women, and create maintenance law, marriage, divorce, and adoption, among other important things. Ambedkar formulated this bill to guarantee that women had full access to rights inside the system. He addressed the subject of property through survivorship, half share for daughters, conversion of women’s restricted estate into an absolute estate, eradication of caste in marriage and adoption, and the idea of monogamy and divorce. In the face of resistance from conservative Hindu males in parliament, Ambedkar’s efforts were stalled and frustrated with this injustice he resigned.

Ambedkar as an intersectional feminist thinker

The reason why Ambedkar is not given importance as a mainstream feminist thinker or philosopher is because of the discipline’s autocratic structure. The key propagator of female subjugation is religion. Religion as an institution has historically contributed to gendered violence, both in writing and practices. Ambedkar’s position as a feminist philosopher was affirmed when he exposed the foundational myths of Hinduism by critiquing texts like Manusmriti, Ramayana, and Mahabharata, which were considered the holy grail of Brahmanical Hinduism.

He argued that women’s position in society declined with the advent of Manusmriti. Manu not only dehumanises and commodifies women, but it ensures their enslavement. Women, regardless of caste or age, are denied the right to be free in any circumstance or stage of life. Killing a woman, in Manu, is termed “Upapataka”, which means minor offense. Women are denied the right to read religious texts, and hence declared unclean.

Also read: An Evaluation Of Social Reorganisation: Revisiting Dr. Ambedkar’s Nationalism

Ambedkar analyses the situation of women in the days of Kautilya and Manu based on his reading of Kautilya’s s. Women enjoyed a much better status in the pre-Manu era, having the right to knowledge, the right to property, the right to divorce, the right to claim support, the right to remarry, and so on. There were also regulations dealing with fines, sanctions, and punishment for males who engaged in extra-marital sexual connections, as well as behaviors like monogamy, widow remarriage, and inter-caste interactions. Men were fined and penalized if they remarried owing to a desire for a male kid without waiting for the prescribed time limit, which was 8-12 years under the provided conditions. Women might go to court to seek justice for slander and violence by their spouses. This comparison showed how Manusmriti has been largely responsible for demeaning the position of women to a slave without any logical explanation.

Ambedkar, while criticising Ramayana, points out how Sita has been commodified by her husband Ram as he terms her a “prize”. he argues that Ram kills Ravana not to save Sita but to proclaim his masculinity and reclaim his honor, i.e., Sita. The text clearly establishes women as a symbol of honor. The text does not stop here but goes on to question the purity of Sita and abandoning her because her “purity” might have been compromised by Ravana. Consequently, Sita had to prove her honor with agnipariksha, as she entered the fire and comes out on the other end without a scratch. Ram took, as Ambedkar says, “the shortest cut”, and “swiftest” path to save his reputation.

Ambedkar contends that such an attitude of women violates the humanitarian idea. He examines Rama’s behaviors through the prism of social philosophy and concludes that they are not only inequitable to a woman but also profoundly immoral. Rama was portrayed to be the hero ignoring Sita’s subjectivity and individuality throughout the epic. As a result, Ambedkar rejects the Ramayana as a guiding principle of an ideal way of life since it advocates the slavery of women in the institution of marriage, which contradicts his concept of social justice. He also dissected the concept of rakshasas that were mentioned in the epics which were metaphors for a group of people who were different and therefore regarded as deviants. Ambedkar’s criticism of Hindu mythology is a broad subject and brings out the discriminatory ideals preached through them.

Feminism, as a movement and theory, has evolved with time and is still in the process of change. It has become a platform that encourages plurality and intersectional narratives to be spoken aloud. Ambedkar’s ideologies are imperative to intersectional feminism. Reducing him to just a “Dalit reformer”, is curbing the potential to realise how his ideas can contribute to the contemporary landscape of feminism. Intersectional feminism has come to the forefront in the last few years. It is essential to build a space of solidarity for women, moving past Savarna powerplay, and Ambedkar’s role is still crucial and relevant in this course of action.

About the author(s)

Simantini Sarkar is a student, writer, and feminist, as well as a literature and film enthusiast. She has completed her Bachelor’s degree from Bethune College, Kolkata, and her M.A. in English from Savitribai Phule Pune University. She writes for various online and offline magazines and is a budding translator. Simantini is also an aspiring research student. Her interests include topics

related to gender, women, politics, and pop culture.