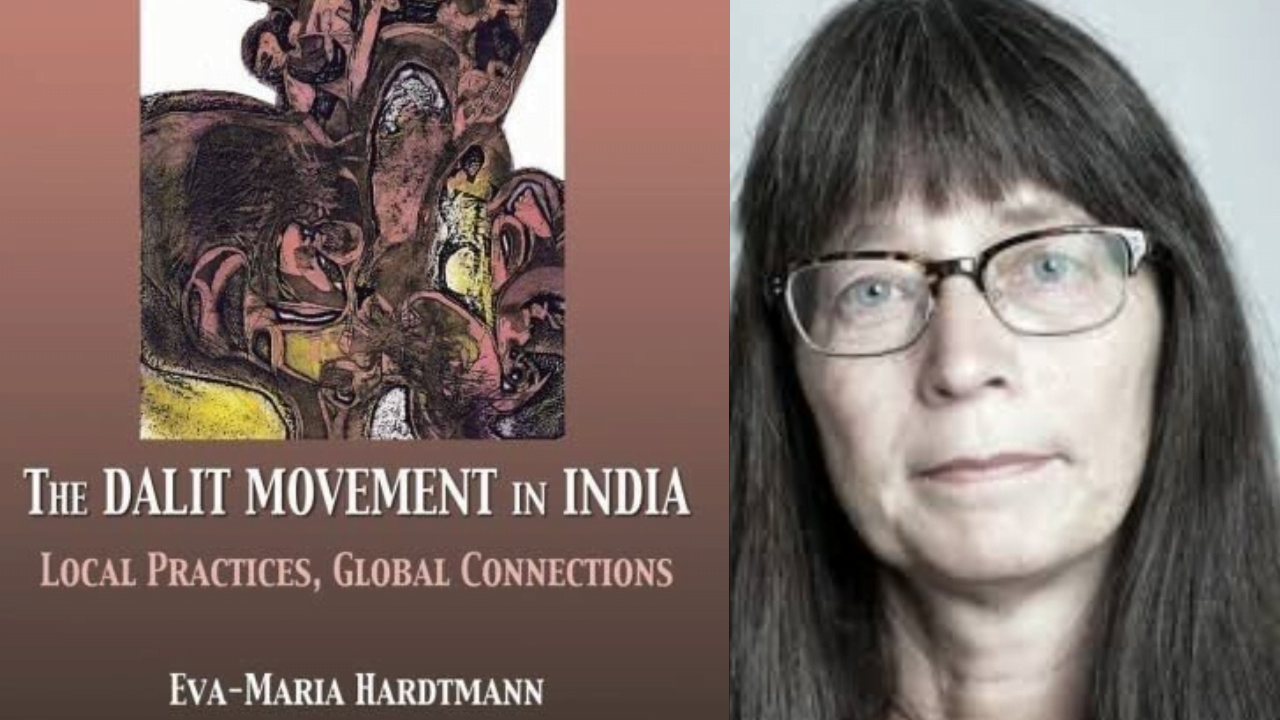

The book The Dalit Movement in India: Local Practices, Global Connections, by Eva-Maria Hardtmann is an anthropological attempt to better understand the Dalit movement. Generally, in the study of social movements, much importance is placed upon the geographical locations but Hardtmann unlike others has placed importance on networks while mapping the movement both locally as well as globally. Thus, making the individuals, associations and their lived experiences the basis of her analysis while tracing the Dalit movement.

Eva-Maria Hardtmann is an Associate Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Stockholm. She specializes in South Asia, mainly India and Nepal. Hardtmann worked on a project where she studied the patterns of activists and their practices in chosen networks in South Asia. This book is an outcome of the same research where she studied the Dalit movement in India by focusing on the networks and practices among Dalit activists.

In this book, Hardtmann when tracing down the history of the movement has talked about the two contradictory traditions that prevailed in the Dalit movement and explained the political and religious reasons behind their development. Looking at the heterogeneity and geographical spread of the movement she has put forth the three most Influential Dalit discourses. But the aspect that makes this book different in the study of the Dalit movement is her focus on Dalit practices and their importance in identity formation. I will put much emphasis on this aspect of the book apart from the contradictory traditions and discourses that she has mentioned and then further put light on the discussion in the book on Local as well as global aspects of the movement.

Another fascinating aspect of the book is her stress on Dalit feminism in a neo-liberal world in which she has not just discussed the discrimination that Dalit women face in social, economic as well as political spheres but also how the peculiarities associated with gender are reversed when applied to not just Dalit women but also Dalit men, this, I feel, is the most interesting observation that she has made in this book.

Traditions of protests and Dalit discourses across the country

Hardtmann talks about the three phases of the movement. The first one was in the 1920s when the Adi Dharma movement began in Punjab amongst the Chamars of Punjab, led by saint Ravidas, a Bhakti movement guru, which was the first attempt to reject the Hindu tradition and form a separate Dalit Identity. Here is where the two traditions emerge within the movement where the inspiration came from the Bhakti movement which is rooted in Hindu tradition but the rhetoric was to dissociate themselves from the Hindu religion based on the notions of the non-Aryan theory which considered the Brahman and Hindu traditions as Indo-European and that Dalits were the land’s original inhabitants.

The 1930s marks the 2nd phase with the emergence of Ambedkar and his thought to completely break away the Dalits from the shackles of Hinduism leading to the conversion at Diksha Bhoomi Nagpur. Here the earlier contradictions acquired a concrete shape in the form of Gandhi Vs Ambedkar debates where Gandhi and the Congress talked of reforming the Hindu religion and keeping the Dalits within the Hindu fold whereas Ambedkar talked about denouncing the Hindu religion and accepting a democratic form of Buddhism.

The 1930s marks the 2nd phase with the emergence of Ambedkar and his thought to completely break away the Dalits from the shackles of Hinduism leading to the conversion at Diksha Bhoomi Nagpur. Here the earlier contradictions acquired a concrete shape in the form of Gandhi Vs Ambedkar debates where Gandhi and the Congress talked of reforming the Hindu religion and keeping the Dalits within the Hindu fold whereas Ambedkar talked about denouncing the Hindu religion and accepting a democratic form of Buddhism.

The Third phase is in the 1970s with the formation of Dalit Panthers in the light of large-scale atrocities on the Dalits despite laws prohibiting discrimination in place, leading to the large-scale propagation of Dalit Sahitya which documented the oppression and rebellion of the Dalits. The Dalit Panthers were Marxist and Buddhist in orientation which was inspired by the teachings of Ambedkar and Phule built upon the legacy of the previous movement and asked for a complete and total change for Dalits in society.

The author has presented three influential Dalit Discourses. First of Dalit Buddhism. She states that Ambedkarite interpretation of Buddhism is something that has always kept Dalits and their Situations in mind, The Buddhism that Ambedkar bestowed on his followers was based on pragmatism and democratic values and hence was apt for the super-exploited Dalits of this land and therefore it’s intelligible and relevant to them. The Second is Dalit Christian Theology which emerged as a counter-theology against the dominant Hindu Theology. And the third is Dalit politics as represented by BSP and RPI in UP and Maharashtra. In all three discourses an anti-Gandhi, Anti-Congress stance is visible which bridges the gap between the three discourses and also marks a continuity in the movement.

Local practices and trans-national aspects, towards building an international discourse

The processes and practices happening in Lucknow, UP and Britain within the diaspora which contains 10% of SC who migrated to Britain during the 1950s and who mostly were from the Chamar community of Punjab have been observed. The Buddha Viharas both in Lucknow and Britain act as a forum of debates and discussions among the Dalit activists and also give them their place to assert and practice their Identity away from the rest of the population. And it is through these discussions and debates new discourses are born that take the movement further to another parameter.

The networks here are more of kinship and friendship and these are fused to form political linkages back in India to that of the BSP and RPI. However, though there is convergence there also is an ambivalence between the activists which are mostly Ravidasis and the Buddhist Ambedkarites where the former is of reformist tendencies which talk about rising in the hierarchy within the Hindu tradition by following a prantik model and having reforms within the Hindu tradition whereas the latter beliefs in the complete annihilation of caste and Hinduism.

Also Read: Book Review | RSS: The Long And The Short Of It By Devanura Mahadeva

These Dalit activists and their discourses have played a vital role to get caste discrimination and untouchability included in the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination, that happened in Durban. The flexibility of language that the activists have followed to first frame caste within the discourse of human rights and later with that of work and dissent and then within that of racism-related intolerance is commendable. Also, it shows how the critique of Gandhi that is very strong within the movement in India has to be read between the lines as Gandhi when caste is taken globally keeping in mind how Gandhi is hugely respected overseas.

Dalit feminism in a neo-liberal world

Dalit women are a minority within the Dalits as they are discriminated against, first because of their gender, next because of their class and finally because of their caste. The neoliberal economy and open markets look at the Dalit man as being incapable of taking care of his family and its needs and hence is denied the peculiar masculinity that is associated with his gender which upper-caste men exhibit.

Similarly, the economy allows Dalit women to step into the economic sphere but when she tries to create their own space and identity, she is then looked down upon and hence denied the feminity that is associated with the upper-caste women. She has given two examples one of Phoolan Devi and the other of Mayawati to show how Dalit women are treated when they try to capture power and assert identity in the economic and political sphere. Thus the peculiarities of gender are revised when applied to Dalit men and women.

Hardtmann has thus given a varied picture of the Dalit movement to better understand processes related to identity formation. She has presented Dalit activists in a multitude of contexts be that at a local/regional level to trans-local to transnational and further to a global context. She discusses the Dalit movement in the framework of social movements to link caste to more general and theoretical discussions both in terms of organisational structure and cultural discourse.

Hardtmann has thus given a varied picture of the Dalit movement to better understand processes related to identity formation. She has presented Dalit activists in a multitude of contexts be that at a local/regional level to trans-local to transnational and further to a global context. She discusses the Dalit movement in the framework of social movements to link caste to more general and theoretical discussions both in terms of organisational structure and cultural discourse.

Also Read: Book Review | New Intimacies, Old Desires: Law, Culture And Queer Politics In Neoliberal Times

She has argued that tensions within the social movements do not necessarily disintegrate the movement as in the case of the Dalit movement, the tensions within the movement have contributed to the growth of the movement and strengthened the cultural Dalit identity. This book has been a great attempt to show how a broad-based heterogeneous Dalit counter-public is reproduced and kept alive and hence has made a significant contribution to the existing Dalit Literature.

About the author(s)

Preeti Patil is a learning enthusiast. She has completed her master's in Politics with a specialisation in International Studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She graduated in Electronics Engineering from RTMNU. Her area of interest is Gender studies, feminist security perspectives, Dalit feminism, Caste & diaspora & affirmative action policies.