Spoilers ahead

At first it may seem shocking to know of the true story May December is based on. Director Todd Haynes had confirmed that the film was loosely inspired by a woman named Mary Kay Letourneau, an American woman arrested in 1997, after she pled guilty to two accounts of rape of a 12-year-old boy named Villi Pulaau, who was her student at the school she was teaching at. She went on to serve a seven-year sentence in jail and gave birth to two children with Villi during her time there. After she completed her sentence, Mary and Villi got married and were together for fourteen years before they finally separated in 2019.

But Haynes’ keen eye does not confine itself to telling the audience what the story of Gracie and Joe was about.

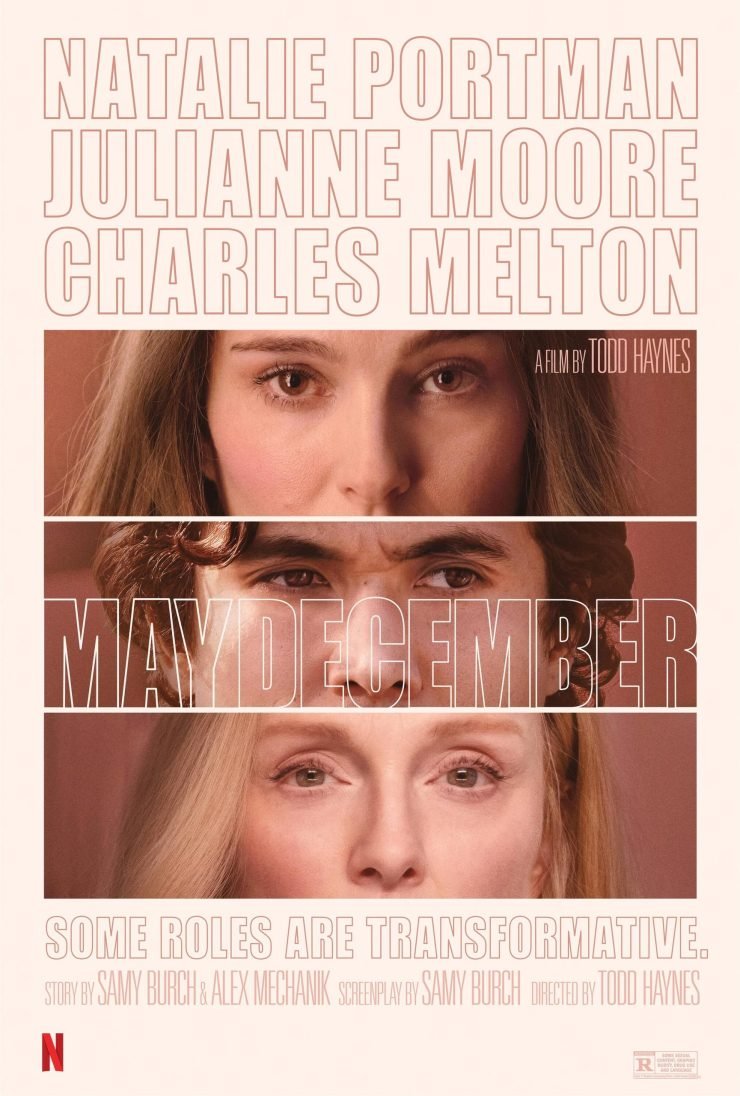

May December, however, doesn’t go so far into their lives. It’s more of a deep dive into a fictionalised few-weeks in the lives of Mary and Villi – here Gracie Atherton and Joe Yoo, played respectively by Julianne Moore and Charles Melton – when an actor Elizabeth Berry, played by Natalie Portman, spends time in their house in Georgia. Berry is slated to play Gracie in an upcoming film and she is portrayed as an actor serious about her craft and wanting to get her role right.

Strong character sketches

But Haynes’ keen eye does not confine itself to telling the audience what the story of Gracie and Joe was about. Of course, to be sure, most films that chronicle a true story also carry with them the director’s own opinions, however subtly conveyed. May December, however, goes slightly deeper. That is to say, the film also tells us what the process of this storytelling is like. In portraying the developing relationship between Gracie and Elizabeth, the film provides fodder for the audience to think about the relationship between a researcher and the researched.

May December opens with Elizabeth Berry having reached Georgia, making her way to meet Gracie and Joe at their home. She holds a box in her hand that looks like a present but when she hands it to Gracie, Gracie knowingly tells her that it’s a box full of faeces That’s part of Gracie’s reputation in Georgia, and she makes no bones about it, proceeding to sanitise her hands as soon she disposes of the faeces. The other part of her reputation is that her friends think it’s fun to be around Gracie when life gets tedious and boring: ‘Gracie always knows what to do’, they say. The film is a sketch of Gracie and Joe’s relationship – the title a metaphor that symbolises the relationship between a young person and one who is considerably older – revolving around the event of their kid’s graduation. The film is a kind of slowly burning march towards that.

In feminist academia, there is a lot of conversation around the relationship between the researcher and the researched. Just the having of such a conversation is often a critique of the anthropological gaze that normalises the “investigation” of one person by another, usually with a stark difference in context. In the case of the film, one gets a sense that Portman’s character feels that she is in a morally superior position than Moore’s character. Elizabeth is here to study Gracie’s character, with the understanding of what such a dynamic between them may entail.

The film is a sketch of Gracie and Joe’s relationship – the title a metaphor that symbolises the relationship between a young person and one who is considerably older – revolving around the event of their kid’s graduation.

In a scene in May December where Gracie is asking Elizabeth why she wants to play this role, Elizabeth replies saying it was because ‘here is a woman who has a lot more to her than I remember from the tabloids and our cultural memory.’ Later on, almost as an extension of this scene, when Elizabeth is speaking to a high school drama class, she is asked why she would ever pick the role of a “bad person”? Interestingly, Gracie’s soon-to-graduate daughter, Mary, is also in this class. Elizabeth replies to this in the manner of “isn’t it obvious why?” She says some of the most interesting roles are of those with moral grey areas – it’s also telling that she cites examples of Medea and Hedda Gabler, even as she talks about wanting to understand such characters.

Nuanced storytelling

But what is compelling about Haynes’ adaptation of this story is that despite the more popular views about Gracie’s notoriety, it’s not easy to tell if there is a “good guy” and a “bad guy” in this film. The blurb for May December simply reads: ‘twenty years after their notorous tabloid romance gripped the nation, a married couple buckles under pressure when an actress arrives to do research for a film about their past.’ But maybe that isn’t only what the film is about: a marriage buckling under the pressure of external scrutiny. It’s the process of that unbuckling that the film wants to dissect. The tabloid romance was sensational for all the wrong reasons, but their marriage survived because the figurative “haters” were all somewhere far away. With Elizabeth’s entry, these “haters” seem to be sitting at their dinner table, coming to visit them at the flower arrangement class, trying to learn how to bake, despite their insistence on their good intentions.

Yet, Haynes also provides avenues of respite for both these characters from their often-stressful storylines. In a scene in May December where Elizabeth is learning how to do Gracie’s make-up from Gracie, they are intimate in an almost equal space. As Gracie tells Elizabeth how she applies her lipstick, she also asks her about herself. Elizabeth says her parents were professors; her mother wrote a book on epistemic relativism that almost produces a spontaneous, ironical chuckle in you. Gracie, un-self-consciously, says her mother wrote her the recipe for the blueberry cobbler. And just for an instant you can see how similar they both are in being affected by their parents and their childhoods so deeply.

And then there is Gracie’s husband, Joe, who is 35 – the same age as Elizabeth, and yet at such different moments in their lives – and sending his children to college. Despite suggesting earlier on that the film is about their relationship, Elizabeth’s is almost omnipresent from the minute she enters their house. Joe’s constant stance is that he loves Gracie and their life together, even while we see him build emotional intimacy with an anonymous texter. Elizabeth and he attempt to build something akin to a friendship, but it also strays into grey areas, in a way that one wonders whether it was only method acting – Elizabeth has to know Joe too if she wants to really know Gracie – or whether there was something more to it.

May December asks many questions and bravely attempts to answer a few of them, especially when at the end of the film we see a series of takes of a single scene for the film that Elizabeth will eventually make on Gracie and Joe.

In a scene in May December where Joe is agitated and telling Elizabeth that he thought they had a connection and implied feeling betrayed, she says: ‘this is just what grown-ups do.’ You can almost hear Joe’s insecurity about his relationships clearly in this moment when he says nothing. When he is on the roof with his son trying marijuana for the first time, he confesses to his son then that he can’t tell if they were connecting or not, betraying the same insecurity about the relationships in his life and what, if anything, he values about them.

The subversions of the plot of May December

Yet, writers Samy Burch and Alex Mechanik manage to turn the tables around at the end of May December. In a pivotal moment in the plot, at the graduation ceremony, when Joe is overwhelmed with all his emotions and Mary is throwing caution to the wind and enjoying herself – after struggling with her mother’s childhood anxieties with her body showing up in various ways in her life, including in picking an outfit for graduation – Haynes unmistakably hands Gracie back her agency that seemed to have been under question since Elizabeth’s entry. She reminds the audience that despite popular opinion, it is, in fact, Elizabeth who is the pariah. That she may have attempted to play juror, albeit inconspicuously, but that Gracie is the main character in her world.

May December asks many questions and bravely attempts to answer a few of them, especially when at the end of the film we see a series of takes of a single scene for the film that Elizabeth will eventually make on Gracie and Joe. She is trying to get Gracie’s character right. Now that she had met Gracie, she knew not only details of the incident that had turned all eyes on her, but also some of the other bits that made her who she was. She knew that Gracie had a passion for baking, that she may have been sexually assaulted as a child by her brothers, and that she sincerely believed it was Joe who had “seduced” her.

She had suggested at some point in the film that it as was important to know of events in Gracie and Joe’s present as it was to know of the past: ‘there are things that exist inside people that don’t necessarily come to head until later, and I try to look for the seeds of those things.’ She knows the strategies of her craft, what will help her to be a good actor. Elizabeth tries to get under Gracie’s skin, both literally and figuratively. But by the end of the film, when we see her taking a series of shots, her eyebrows knit in concentration between shots, it’s as if she is trying to figure out the answer to that most eternal of questions of whether one can ever really know the other.

About the author(s)

Himalika is slowly beginning to get the hang of being an adult, despite being a bad cook. She will take most things with a sense of humour and is constantly striving to infuse feminist practices in her research.