Do you know the 18th-century Company musician, William Hamilton Bird, wrote of the gat nikās (an opening gliding walk in kathak dance) of North Indian tawaifs/courtesans with the same frenzied admiration we recently harbored for Aditi Rao Hydari’s “Gaj Gamini” chal from Heeramandi? Same gait, same response—just 300 years apart! Indeed, the recent commotion around Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s miniseries takes the wraps off our uneasy yet indulgent relationship with historical tawaif culture. It makes one thing clear. The tawaifs still hold sway—over us, the Indian audience, and over Bombay cinema.

Indeed, the recent commotion around Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s miniseries takes the wraps off our uneasy yet indulgent relationship with historical tawaif culture.

Ruth Vanita’s Dancing with the Nation: Courtesans in Bombay Cinema describes tawaifs as women who made a ‘living by singing, dancing and conversing with men’. Though considered sexually independent and powerful skilled musicians, the Indian government’s 1952 abolition of zamindari dealt a deathblow to their patronages. Most impoverished courtesans embraced sex work to survive and ‘a new type of courtesan-cum-sex-worker’ came into existence.

Bombay cinema realistically captured this shift on screen—albeit with a pinch of nostalgia, ethical socialism, and reformist feminism—subscribing to the social reformist narrative of women being forced into the profession by abduction or for monetary reasons. Its portrayals of the beloved dancing girl have been, at best, ambivalent and, at worst, a derogatory concoction of sordid misrepresentations, fetishisation of suffering, and stereotypical degeneration of artistic practices like mujras and mehfils.

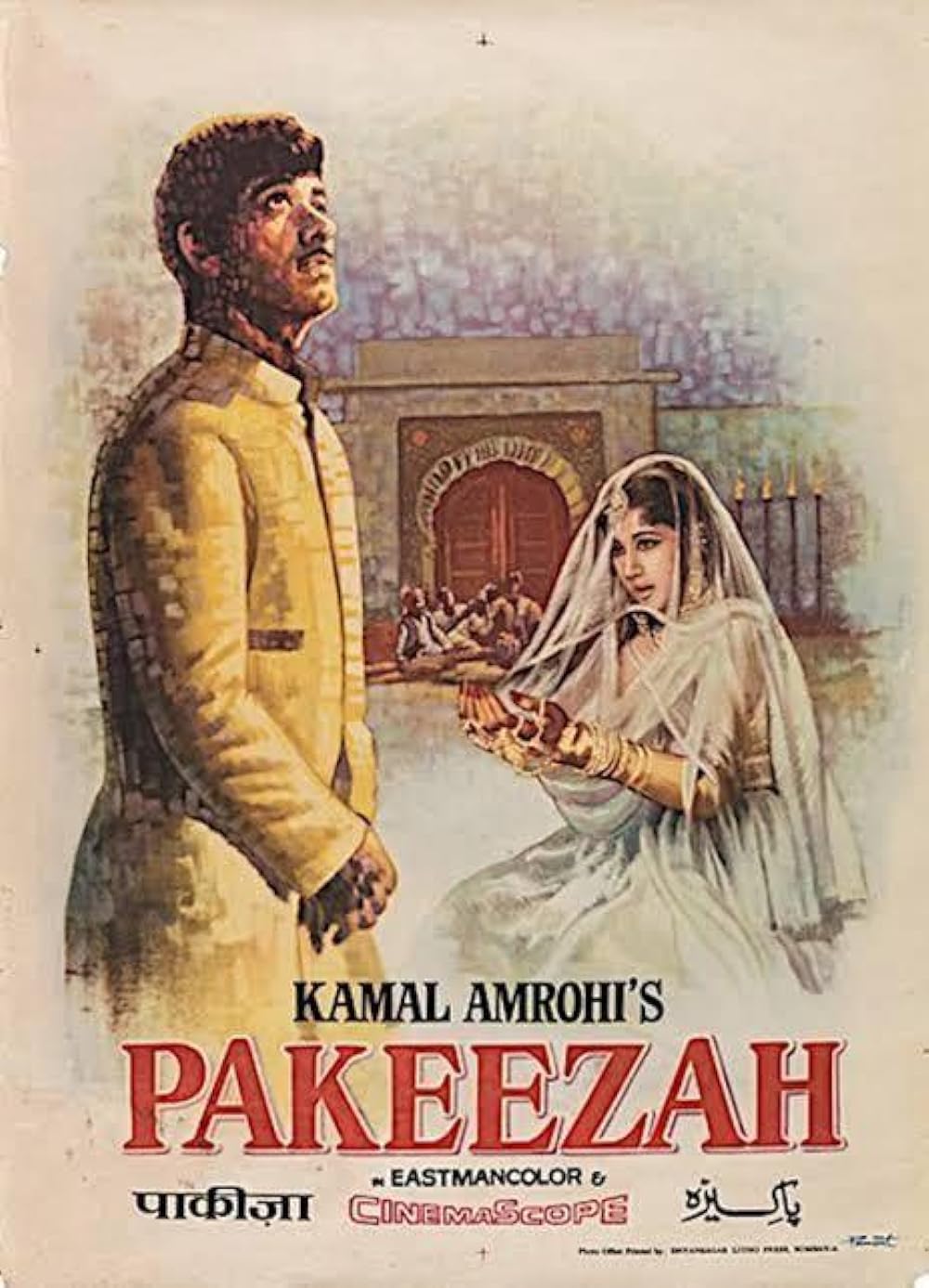

Despite this time-tested trend, Hindi period dramas like Mughal-e-Azam (1960), Pakeezah (1972), Amar Prem (1972), Devdas (2002), Heeramandi (2024), etc. have striven to rescue and reclaim tawaif culture from the colonial gaze and the compressed categories of mere “dancing girls” or lowly “prostitutes”. A unique tool in this attempt is the introductory “song of modesty” that unlikely pairs the central characters of the tawaifs with well-respected songs of laaj and sharam.

These prefatorial mujras voicing moral anxieties and a fuss over respectability inaugurate the persona of the tawaif in its most pristine association with the arts and lack the exaggerated overtures of suffering that characterise the figure in the climax of most Hindi films.

These prefatorial mujras voicing moral anxieties and a fuss over respectability inaugurate the persona of the tawaif in its most pristine association with the arts and lack the exaggerated overtures of suffering that characterise the figure in the climax of most Hindi films. The song and dance numbers refurbish and/or replicate classical and semi-classical Hindustani music and dance traditions (related to thumri, khayal, tappa, bol banao, ghazal, dadra and folk music) to remind the modern-day audience of the historical tawaifs’ highly prized skills and societal respect in glittering and classy salons—feted by the rich, the rulers, and the gentry.

Simultaneous, the lyrics of these songs become an agency to assert the tawaifs’ virtue, conscience, and incorruptible helplessness—qualities that attest to the purity of their souls and make them redeemable figures despite their non-consensual, overtly sexual, and morally laxing professions. A regular in the genres of courtesan films and the Lucknow-based Muslim social, these mujras tow the thin moral-immoral line and help set the tone for the portrayal of courtesan culture as well as the audience’s perception of moral and social sanctimony in the respective cinematic works.

The moral dilemmas of the tawaif in mehfils of modesty

Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah (1972) introduces the central character of the young tawaif, Meena Kumari’s Sahibjaan, with Inhi Logo Ne, a Poorbi thumri doubling as a protest anthem that voices the moral anxieties of public kotha women. The song conveys the making of the tawaif through allegories of the dupatta (veil). Representing a woman’s modesty and reputation (that only men can ruin), the dancing girl’s ‘gulabi dupatta’ is claimed as a social construct that originates in the hands of the modistes—the clothier and the dyer—and gets destroyed by the unruly soldier in the open bazaar.

Throughout the mujra, Sahibjaan wears and removes her veil several times—imitating the sexual attention that comes with an immodest pose. Yet, she transcends the implications to reclaim a dancing girl’s right to her sentiments and honour as any other woman. The introductory song becomes her agency in asserting her purity. Because Pakeezah construes Sahibjaan as a romantic heroine, the song compliments the film’s title. It steers the figure of the tawaif away from the colonial gaze and convictions of prostitution by equating dancing with oppression.

Pakeezah went on to inspire happier endings for cinematic courtesans. However, the moral anxieties of the tawaif herself and those of the patriarchal society surrounding the “bazaaru aurat”/“kothay-wali” persist in portrayals of tawaif culture.

The 1985 film Tawaif introduces Rati Agnihotri’s courtesan Sultana with a mujra bordering on themes of modesty in a glitzy indoor kotha. A quintessential product of the 1980s’ Bombay cinema, the film turns didactic from the very first song, Jabon Anmol Balma. In the mehfil, Sultana describes how a tawaif enters the dancing girls’ bazaar, adorned with “kajara” and “mehndi”, and entices clients with her beauty and youth. She mourns that a tawaif is a perpetual bride who celebrates her nuptial night everyday.

As Sultana laments the transactional aspects of courtesan culture, her lyrics jarringly pair the modesty and privacy of respectable women with the public and sexual nature of the courtesan profession.

Her song betrays how Tawaif perceives the eponymous character as both sex worker and dancing girl—upholding the colonial preoccupation with chastity. As Sultana laments the transactional aspects of courtesan culture, her lyrics jarringly pair the modesty and privacy of respectable women with the public and sexual nature of the courtesan profession.

The classical Nāyikā’s laaj and sharam in mehfils of modesty

Songs of modesty in tawaif culture are not limited to modern-day cinematic compositions, going back to the Ashta-Nāyikās (heroines) of ancient Sanskrit treatises, Hindu religious traditions, and medieval Riti poetry. These narratives, encouraged by the bhakti movement, entered both courtly and devotional tawaif performances. The major compositions drew from the Bhagavad Purana, delegating Lord Krishna the role of the nāyākā and his legendary sweetheart, Radha, the roles of various nāyikās. Bombay cinema too upheld this theme in tawaifs’ songs.

In K. Asif’s magnum opus Mughal-e-Azam, Madhubala’s Nadira is re-introduced as the famed dancing girl Anarkali at Emperor Akbar’s court with the flirtatious thumri Mohay Panghat Pay. Anarkali imitates Radha’s concerns for her modesty after being drenched from the pierced pitcher and voices the legendary gopi’s fear for her respectability as the latter feels helpless against Krishna’s charms. The reference to ghunghat (the veil) in her lyrics and graceful gait is subtly erotic.

Essentially an elegy of a chedchaad (playful harassment) scene, the song establishes Anarkali as a classical nāyikā who appropriates Radha’s moral and romantic anxieties about forbidden love. Coupled with the performance, it paradoxically recreates a mythical space within the confines of the dancing floor that legitimises her proscribed legendary love for Prince Salim.

Similarly, Madhuri Dixit’s Chandramukhi serenades to Kaahe Cheddh Mohe in Devdas (2002) when she is introduced on screen. With Radha as the protagonist, the song narrates the impact of Krishna’s teasing and kissing on her. It talks of Radha’s emotional turmoil as her veil slips from her head—symbolising both a loss of modesty and the baring of her illicit romantic feelings.

With Radha as the protagonist, the song narrates the impact of Krishna’s teasing and kissing on her. It talks of Radha’s emotional turmoil as her veil slips from her head—symbolising both a loss of modesty and the baring of her illicit romantic feelings.

Chandramukhi’s introductory song of modesty is a confident ballad focusing on Radha’s sexual desires. However, the lyrics stop short of establishing the tawaif as the legendary heroine because the film sees her as Meera—the public foil to Radha—who worshiped Krishna through unconditional personal surrender and unwavering faith.

In a sharp departure from her spiritual predecessors, Bibbojaan’s introductory song addresses the issue of women’s modesty sans metaphors.

In sharp contrast, Shakti Samanta’s Amar Prem (1972) abandons the more irreproachable chapters of Krishna-Radha’s love story in favor of the full-blown adulterous episodes. The film introduces the tawaif, Sharmila Tagore’s Pushpa, with Raina Beeti Jaaye—a bhajan wherein Radha, as a virahotkanthita nāyikā, expresses an anguished longing for her beloved Shyam (Krishna). The subtle hints of unfaithfulness and lust in the lyrics like ‘sautaan’ and ‘taan maan pyaasa’ nonetheless get refuted by Pushpa’s devotee-like appearance and the mandir-like setting of the kotha. Through the introductory song, Samanta reclaims Pushpa from the label of the common prostitute; instead, she becomes a sacrosanct courtesan who sings for a living.

Heeramandi gifts the latest and most audacious installment of the tawaif’s introductory song of modesty. The thumri Saiyaan Hatto Jaao opens with Rao Hydari’s flamboyant Bibbojaan carolling to her aristocratic patron. The lyrics voice the moral anxieties of a married abhisarika nāyikā who prepares to leave her lover after a night of passion. The protagonist nāyikā expresses concerns over facing social questions about her nocturnal whereabouts and fears dying of ‘laaj’ and ‘sharam’ if she doesn’t return home soon.

In a sharp departure from her spiritual predecessors, Bibbojaan’s introductory song addresses the issue of women’s modesty sans metaphors. She refuses to be apologetic of her profession and defies the narrative of the courtesan as the fallen woman. Armed with the fiery and grey “Bhansali” brand of feminism, her song critiques the hypocrisy in societal expectations and the gendered nature of propriety and marital fidelity.

The anonymous author of the Ghunyat al-munya, a 14th-century Indian treatise, described the mehfil as the place where the patron rigorously assessed the skills of those employed by him/her, whether musicians, scholars, or poets. The introductory mujra in Bombay’s courtesan films is a similar space wherein the respective tawaif’s modesty is examined or manifested by an audience inching to prove its moral mettle. And somewhere it is heartening to see that both filmmakers and the audience have graduated from their preference for the tawaif’s self-directed guilt to her breaking the male gaze and the making of her “immorality”.