Videos of Indian women draped in sarees strolling through the streets of foreign countries have become trending on Instagram. The hook is usually the reactions of foreigners, and the comment section is packed with Indians beaming with a sense of glory—nothing can beat an Indian woman’s dedication to upholding her culture and national identity. The need and expectation of carrying cultural markers are so deep-seated that one often fails to realise that their choices are designed to follow gender expectations.

One can argue that Indian women like wearing traditional attire in a Western setup, and that might as well be true, but often personal preferences are shaped by social conditioning. Hindi mainstream films have played a mammoth role in giving birth to the desire to drape a saree and pose in front of picturesque landscapes in foreign countries. And inevitably, social media influencers have taken over the role, consciously or unconsciously.

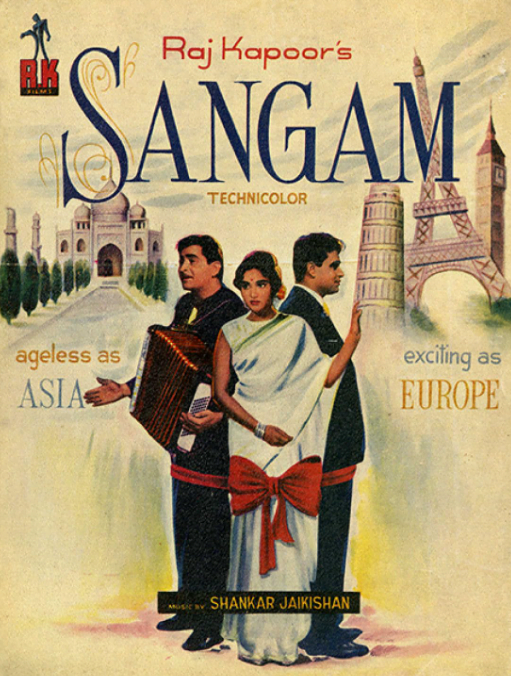

When Indian couples travel abroad, it is typically the women who are assigned the role of protecting national identity and integrity. Hindi mainstream films such as Sangam (Raj Kapoor,1964) illustrated how a good Indian woman is allowed to enjoy herself with all the commodities present in the foreign location, but she must perform her traditional duty when required. Since India’s independence, men navigated the outside world in Western attire, while women were tasked with preserving Indian culture. The desire to travel abroad gained momentum in the 1960s. The 1960s, being a period of turmoil for India (the death of Jawaharlal Nehru, the Sino-Indian war, the Indo-Pak war, and the currency crisis), shook national consensus regarding the Nehruvian socialist vision of the formation of the nation-state.

The nationalist limit on consumption faced pressure as the indecisive condition of the nation led to the middle class expressing their desire to travel as a way to escape and find peace. The reflection of this desire is evident in Hindi mainstream films of the 1960s. The stark shift from the nationalist films of the 50s to the vibrant and colourful films of the 60s with a hint of consumerist desire is rooted in technological advancement as well as political anxiety regarding the future of the nation. Films such as Sangam (Raj Kapoor,1964) and Evening in Paris (Shakti Samanta,1967) were both a testament to the new middle-class desire as well as a distraction from the political unrest.

The unwritten travel rules for ideal Indian women

In both Sangam and Evening in Paris, Vyajanthimala as Radha and Sharmila Tagore as Deepa perform their duty as the upholder of national identity when they step foot on foreign soil. The scene where Radha refuses to kiss her husband Sunder at the Eiffel Tower and immediately pulls her pallu (loose end of her saree) to cover her head—not only highlights how an ideal Indian woman is expected to behave abroad but also how foreigners (locals) appreciate Indian culture. The rejection was followed by appreciation. Two Parisian women asked the couple whether they were from India, and the confirmation led to applause. The applause acts as a celebration of their decision to abide by traditional values. It also illustrates the appreciation for Indian culture in the West.

Evening In Paris pushed the envelope a little further. Sharmila Tagore was featured in Filmfare magazine in a bikini before the release of her film, making her the first Indian female actor to do so. Her bold move stirred controversies, leading to Tagore apologising and not wearing a bikini again. In the film, Tagore sported a leotard rather than a bikini, and in an interview, she expressed how she wanted to wear it for the song sequence, but Samanta objected to the idea.

What is striking is that after the song sequence, Tagore, in a saree, is seen on the Eiffel Tower with her lover Shyam, and when he expresses his desire to kiss her, she stops him to remind him, “Mein ek Hindustani ladki hu… aur Hindustani riwaz ki mutabik woh shaadi ke baad “(I am an Indian woman, and according to Indian traditions, we can kiss only after marriage). Indirectly reminding the audience that Deepa is still rooted in traditional values. She was modern enough to wear a leotard but traditional enough to reject a kiss. The risk of presenting to be too bold was avoided with dialogues asserting the film’s stance.

Difference in expectations

With the Indian market finally opening up in the 90s, the shift from socialist tendencies to capitalist spending habits manifested on screen. Indian women, who have by now been a part of the workforce for over two decades, were not only traveling abroad but also settling there. What is intriguing is the difference in expectations from an Indian woman traveling abroad versus an NRI.

In Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (Aditya Chopra, 1995), Kajol’s character, Simran Singh, was born and raised in London. From leather skirts to microminis, Simran was allowed to wear Western outfits as long as she respected her Bauji (father), and married a man of her father’s choice. In Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (Karan Johar, 2001), the expectation from NRIs further evolved with Kareena Kapoor’s iconic character, Poo. She did not care about Indian tradition, spoke accented Hindi, and wore Western outfits.

In contrast, Kajol’s Anjali Sharma, who grew up in India, was rooted in her traditions. Her morning started with prayers and bhajans, and she spoke about her culture with a sense of pride. While the NRI women were spared for their clothing choices, the need to fix them remained. Poo transformed into a sanskari (traditional), bhajan-loving woman, all thanks to her sanskari boyfriend, Rohan (Hrithik Roshan).

Hindi mainstream films have consciously established an unwritten rule for Indian women travelling abroad on honeymoons or vacations with their significant other—they must be the torchbearers of Indian culture. In Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (Sanjay Leela Bhansali, 1999), Nandini (Aishwarya Rai Bachchan) walked the streets of Italy searching for her lover, Sameer, invariably in sarees.

Coping with patriarchal expectations

As India transformed into a capitalist nation and a consumerist hub, the urban female population became more receptive to Western clothing. But there is a clear distinction between the outside and the inside. At home, in the presence of the patriarch, Indian women, at large, are expected to be in their traditional attire. For single Indian women, traveling abroad is a recent phenomenon, and it is deeply intertwined with class and caste politics. Women with the means to travel solo are challenging traditions, though that percentage remains quite low. Many are often told that they can only travel after marriage in the presence of their new guardian, the husband.

A woman with too many independent experiences does not fit the definition of the ideal Indian woman and is thus considered a failure in the marriage market. From fathers dictating their lives after birth to their husbands taking over the role of the patriarch, Indian women struggle to find their agency.

Travelling often is a way to escape from norms and expectations, but that is not entirely true for most married Indian women. Patriarchal expectations are so deeply ingrained that even in a foreign country one is afraid of not living up to them. Coupled with that is a sense of pride in abiding by gender norms, especially in a Western country, because the most iconic Hindi mainstream films one grew up watching have celebrated them.

However, it is often overlooked that these expectations are solely imposed on women. At most international film festivals or events, Indian celebrities and artists are typically seen wearing sarees, and those opting for Western outfits often face criticism on social media. The problem is not in showcasing Indian culture, but why is the onus always on women? Challenging norms and expectations and making informed choices can initiate change. Instead of submitting to traditions, we must determine them through a critical feminist lens. It also might be worth asking whether the unrealistic and deeply patriarchal standards set for women by Bollywood are truly worth celebrating.

References:

- Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and its Fragments: Colonial and Post-colonial Histories (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1993)

- Ranjani Mazumdar, “Aviation, Tourism and Dreaming in 1960s Bombay Cinema”, Bioscope: South Asian Screen Studies 2011

- M. Madhava Prasad, Ideology of Hindi Film: A Historical Construction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998)

- Subhash K Jha, “Samanta didn’t let Sharmila wear bikini”, Times of India, created on April 11, 2009. (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/news/samanta-didnt-let-sharmila-wear-bikini/articleshow/4385986.cms)

About the author(s)

Srijoni Rudrais a digital writer who would like to explore the intersection of cinema, gender, and culture through her work. She holds a Master's Degree in Film Studies, is a regular contributor at Digital Mafia Talkies, and has also spent two years teaching film studies at the G.D Birla Centre of Education.