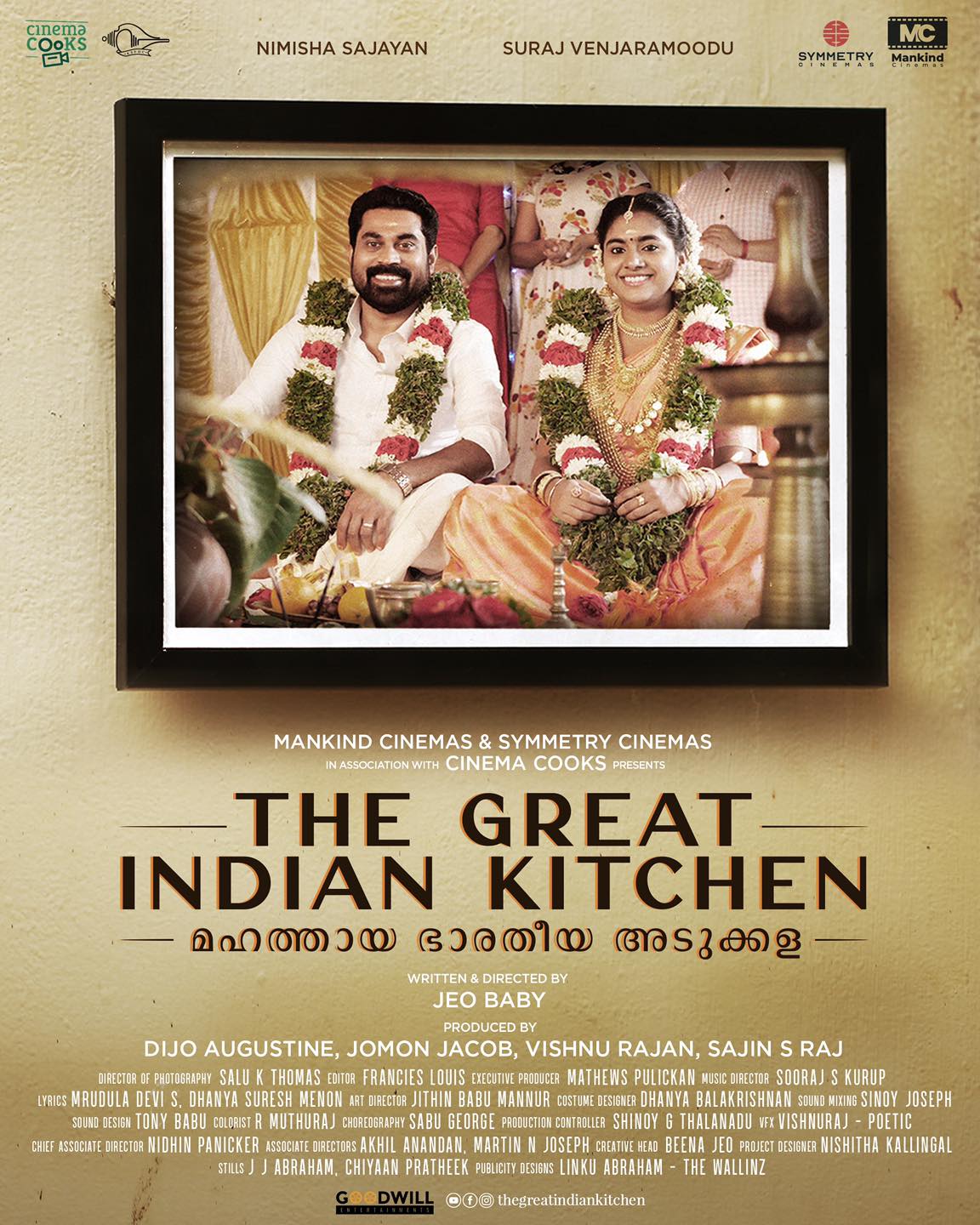

From a long period of time, cinema has been a powerful medium of challenging societal norms and expectations regarding gender roles. Women, especially those married into a patriarchal family system, face unique hurdles which are analysed in The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), directed by Jeo Baby and its Hindi remake Mrs. (2025) by Arati Kadav.

Women, especially those married into a patriarchal family system, face unique hurdles which are analysed in The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), directed by Jeo Baby and its Hindi remake Mrs. (2025) by Arati Kadav.

Both films offer different perspectives on oppression, resistance, and agency. They follow the journey of a newly married woman who initially accepts her new role in a traditional household. However, as days turn into weeks, she uncovers the harsh reality that her marriage has robbed her of her identity and reduced her to the status of an unpaid domestic worker. Even though both the films address the same core issue, the manner in which the story is dealt with is completely different in each, giving audience diverse experiences.

Narrative style and directional approach

Regardless of the fact that both films follow the same plot line, their way of storytelling differ. The Great Indian Kitchen takes a slow and immersive approach, relying on long, uninterrupted shots to highlight the protagonist’s monotonous and exhausting routine whether it be washing endless piles of dishes, kneading dough, or scrubbing the floor. These scenes are purposefully stretched to make the viewer feel her exhaustion. The camera often zooms into small details such as oil stains on her clothes, sweat on her forehead, and the clinking of steel plates which creates a visceral experience.

On the other hand, Mrs. follows a more structured Bollywood-style narrative, with slightly more character interactions and a clearer progression towards the climax. While it still captures the repetitive nature of the protagonist’s life, it does so through shorter scenes and there are more close-ups emphasising emotional moments. The film allows its protagonist to voice her frustrations more openly, making it more direct in its feminist messaging. The Hindi adaptation ensures that the story is accessible to a broader audience while staying true to the essence of the original.

As a result of this, The Great Indian Kitchen comes out as a more documentary engaging style of filmmaking, while Mrs. translates that knowledge into a more emotionally expressive and dialogue driven context.

Portrayal of domestic labour and patriarchy In Mrs. and The Great Indian Kitchen

In The Great Indian Kitchen, the protagonist’s entire existence revolves around the kitchen, symbolising how women are expected to serve without recognition. One of the most striking scenes occurs when her husband and father-in-law are done eating and simply push their plates away, expecting her and her mother-in-law to clear them without a word of acknowledgment.

The film also highlights the strict gender division in household duties, showing the husband practicing yoga while his wife struggles with housework.

The film also highlights the strict gender division in household duties, showing the husband practicing yoga while his wife struggles with housework. This is a visual representation of the deep-seated sense of entitlement men tend to have in such environments.

Mrs. tackles the same issue but with more verbal confrontations. While the protagonist continues to do all the housework, there are moments where she questions her role openly, leading to heated arguments with her husband. For instance, when they’re visiting Richa’s friends for dinner, Diwakar, Richa’s husband offers to clear up the plates only when he notices her friend’s husband doing so. However, at home, he refuses to even go and bring medicine for his wife, reflecting the patriarchal mindset he grew up seeing in his father.

This hypocrisy is a central theme in both films, men enjoy dictating how things should be done in a home but do not participate in the work themselves. Also, they believe in the idea that caregiving is only the domain of women.

Sexual entitlement and lack of emotional intimacy

Both films depict how women’s bodily autonomy is ignored in marriage, and both protagonists openly voice their discomfort regarding intimacy.

In The Great Indian Kitchen, the wife tells her husband that she wants to experience intimacy and not just tolerate it. However, her words are met with complete indifference. The scene where the husband initiates sex is filmed without passion or consideration, reinforcing how her desires are irrelevant in the marriage. When she voices her discomfort, he simply ignores her and turns away, emphasising the emotional disconnect, treating sex as nothing more than his right and her as a tool to satisfy his needs.

When she voices her discomfort, he simply ignores her and turns away, emphasising the emotional disconnect, treating sex as nothing more than his right and her as a tool to satisfy his needs.

In Mrs., the protagonist also brings up her dissatisfaction, but the film allows for more explicit conversations about the issue. She tells her husband that sex without foreplay or emotional connection feels painful, to which he cruelly replies ‘How am I supposed to feel anything for you when you always reek of the kitchen?‘ Just the mere act of asserting her own needs puts Diwakar in a defensive position, as if pleasure and desire are privileges reserved only for men.

Thus, while both films highlight sexual entitlement and a lack of emotional intimacy, The Great Indian Kitchen conveys this through prolonged silence and passive avoidance, whereas Mrs. incorporates a more direct confrontation of the problem.

Menstruation and the treatment of women as impure in Mrs. and The Great Indian Kitchen

Both films explore how menstruation is still treated as a source of impurity in many households.

In The Great Indian Kitchen, Nimisha (the wife) is isolated in a separate room, she cannot touch anyone, and is given separate utensils to eat from while she is on her periods. When she mistakenly touches her husband, played by Suraj Venjaramoodu, a priest advises him to “purify” himself by eating cow dung or taking dips in river water. This scene exposes the regressive customs that still exist in many households, where menstruation is seen as impure, forcing women to endure humiliating restrictions.

This scene exposes the regressive customs that still exist in many households, where menstruation is seen as impure, forcing women to endure humiliating restrictions.

In Mrs., this issue is addressed more subtly. The protagonist is simply asked to stay out of the kitchen during her cycle. But there are no overtly superstitious rituals like in the original.

This difference makes Mrs. slightly less intense in its criticism of such customs while an unapologetic realism of culturally specific oppressive rituals is shown in The Great Indian Kitchen.

Characterisation and performances

Nimisha Sajayan who plays the protagonist in The Great Indian Kitchen, gives an outstanding restrained performance, she relies more on body language and facial expressions instead of dialogues. Her tired eyes, slumped shoulders, and hesitations speak volumes. Her transformation from silent suffering to rebellion is powerful, especially when she finally reaches her breaking point and rejects the oppressive environment around her.

As showcased in the ending scene, where she walks out of the house while a religious ceremony is in progress, she walks past a group of women protesting the Supreme Court verdict in the Sabarimala temple entry case, allowing women entry to the temple. Here the symbolism is clear her personal rebellion is part of a larger feminist movement.

Sanya Malhotra in Mrs. brings a different kind of energy to the role. While she also portrays silent suffering, a considerable amount of her frustration is allowed to come out, making her performance far more expressive. Her confrontations with her husband, whether refusing to delete her dance videos from social media or serving dirty water to guests as a gesture of rebellion make her resistance more appealing to mainstream audience, whereas Nimisha Sajayan’s character suffers silently for longer periods before taking a stand.

The male characters in both films are uncannily similar, they are not openly abusive, but are deeply conditioned by patriarchy.

The male characters in both films are uncannily similar, they are not openly abusive, but are deeply conditioned by patriarchy. For instance, the husband in The Great Indian Kitchen is particularly chilling in his emotional detachment. Even when his wife is clearly struggling, he never expresses concern.

The husband in Mrs. is a little more expressive, but he still carries the same mindset viewing his wife’s labour and sacrifices as natural and normal. Both men firmly believe that it is a wife’s duty to serve her husband, like their mothers did before them.

Conclusion: two films, one powerful message

Both The Great Indian Kitchen and Mrs. serve as powerful feminist critiques of patriarchal norms, but their way of execution differs. The Great Indian Kitchen is a slow, immersive experience that compels the audience to feel the protagonist’s suffocation, while Mrs. follows a more conventional narrative with clearer emotional beats and confrontations.

The original Malayalam film is unfiltered, silent, and unflinchingly realistic, while the Hindi adaptation is more emotionally direct and a bit diluted in certain aspects perhaps for the desire to reach wider audiences. This difference could be identified even towards the end of the films.

Both films conclude with songs about women’s empowerment, but their tones are quite different.

Both films conclude with songs about women’s empowerment, but their tones are quite different. The Great Indian Kitchen ends with a powerful and rebellious anthem calling women to rise ‘Oh woman, march on, enough of your grief… you are a relentless stream, spread across the world.’ The visuals of a girl in background breaking free from chains and finally claiming her own space supports this message. In contrast, the song in Mrs., Baar Baar, has a gentler, poetic tone ‘We will rise each time and blossom.‘ Although still hopeful but it lacks the same fiery, revolutionary energy of the original.

However, despite of these variations, both films successfully highlight the invisible labour, emotional neglect, and lack of autonomy faced by countless of women in Indian households, making the audience question deeply ingrained gender roles. They challenge the normalisation of women’s oppression in domestic spaces. Each in its own way stands as a tribute to the power of storytelling in driving social change.