Often people get confused about learning academic concepts, especially those related to feminism. Whether it is intersectional feminism, kyriarchy, or feminist autotheory, it is considered a daunting task to deal with them. It seems almost impossible to understand the experiences of the marginalised through academic concepts in one go. Nevertheless, it can fascinate those who are justice seekers, and inculcate consciousness in those who are yet to awaken. One such term is “feminist autotheory,”; Lauren Fournier used the term in “Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism.”

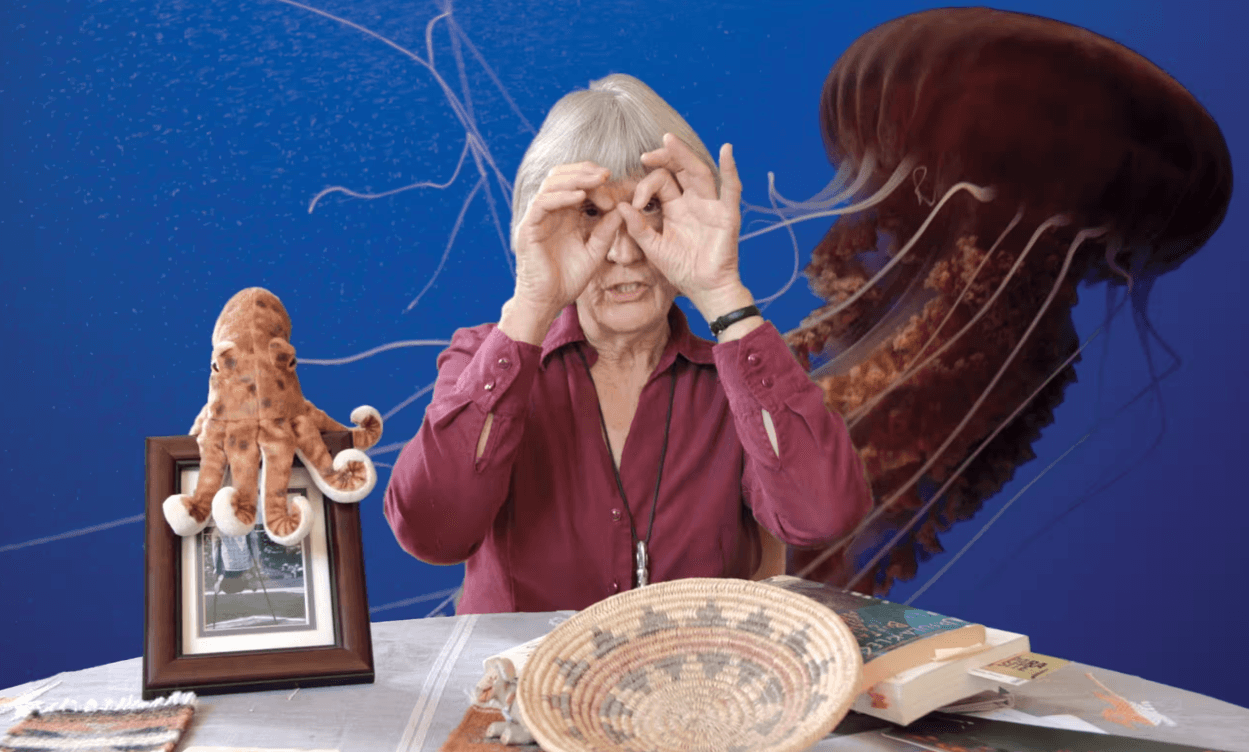

Lauren Fournier is a writer and interdisciplinary researcher with an interest in the intersection of art, science and humanities. Fournier is well-known for penning autotheories, autofictions, non-fiction, and hybrid genres. Her influential work “Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing and Criticism” provides a critical analysis of the term. The MIT Press published the book; it was featured and reviewed in the Los Angeles Review of Books, High Theory, and Contemporary Women’s Writing and Art in America. The term gained significant popularity with Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie (2013), and Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts.

The term feminist autotheory was brought into critical analysis with Fournier’s work and had been used in literary texts since the 2010s. It was used in conversations about books in which a blend of memoirs and autobiographies with theories and philosophies was touched upon. In this book, Lauren is credited with having moved the term beyond its conventional bounds to other disciplines. She argues that feminists maintained a prolonged segregation between theory and practice, life and art, work and the self. Feminist autotheory is an approach that challenges conventional methods and brings forth alternative approaches to share the experiences and struggles of those who are on the margins. In short, through her work, she repudiates a general definition of the term.

Lauren Fournier and her arguments

In her work, she talks about feminist autotheory and its emergence in the 1960s, and its consolidation between 1998 and 2005. It was the time that marked its distinctiveness as a separate category of works that was different from autobiographies and memoirs. Since the 2010s, the term has been in circulation in gender studies, women’s studies and autobiographical studies. First, it is important to understand the term autotheory, which is split into two parts: the ‘auto,’ means self that is combined with philosophy or theory. In simpler terms, this means being self-aware.

In her book, she argues that the concept of autotheory challenges traditional boundaries by mingling personal narratives with theoretical discourses. There has been a long maintenance of the gap between personal experiences and theoretical analyses. There are multiple categorisations, such as autobiographies, fictions, and theories. In her work, she tries to blur the segregation maintained between personal experiences and theories. She understands one’s personal experience as a legitimate source of knowledge. She even seeks an interdisciplinary approach, such as criticism, art and writing, to learn about feminist practices. To be precise, according to her, one’s lived experiences can form theoretical insights.

According to Lauren Fournier, the origin of feminist autotheory is traced back to feminist conceptual art, video art, performance, and body art, as well as cross-genre writings by women of colour like Audre Lorde, Gloria E Anzaldua, and bell hooks. Mary Wollstonecraft and Sojourner were the first women who are remembered for having formed a basis for autotheoretical approaches. However, the term gained prominence in the 2010s. Although it may sound new, its impulse has existed in philosophy for centuries. Autotheory has long been a significant part of feminist movements. Feminists have made contributions by turning personal experiences into collective actions.

Feminist autotheory has never remained static but has been dynamic. For decades, it has evolved and interconnected with feminist art, literature, and activism. Lauren mentions traditional feminist approaches and their limitations. She critiques the well-known phrase ‘the personal is political.’ The phrase which was popularised by Carol Hanisch, according to Lauren, does not, all in all, incorporate the experiences of marginalised groups who are discriminated against based on the intersection of different identities. This is because this phrase focuses on some privileged sections’ experiences. Marginalised people remain vulnerable to multiple forms of oppression. In the introduction to the book, she defines autotheory within the parameters of feminism.

Fournier challenges the oversimplification of the personal is political

Lauren Fournier challenges the oversimplification of the phrase ‘the personal is political.’ She wants to redefine the phrase to adapt to autotheoretical practices. She wants to share deep insights about personal narratives and experiences that are shaped by different identities such as gender, class, caste, race, etc. She further argues that this intersectional framework challenges traditional feminist discourses that maintain the gap between autobiographies and theories. To be concise, she does not criticise but modifies the phrase to incorporate contemporary issues.

Hence, she wants antitheoretical approaches to deepen the meaning of ‘the personal is political,’ by making individuals share their personal experiences, and these can even differ. For instance, a Black woman may have a different experience from that of a white woman, or a lowered caste woman may have a different experience from that of an upper-caste woman.

Fournier wants the feminist discourse to be Inclusive

Lauren wants to extend the feminist discourse to be inclusive and reflective of the marginalised experiences of intersecting groups based on race, class, ethnicity, language, etc. According to her, there were failures and limitations in feminist movements that could have been noticed. It means that the historical mainstream feminist movements sidelined the marginalised voices of women of colour, and others who fell outside the mainstream.

She notices an unwillingness within feminist spheres to address intersectional issues. According to her, at the inception, the dominant feminist theories neglected autobiographies and personal narratives that form a significant part of the feminist discourse. This led to a narrow understanding of feminism.

About the author(s)

Nashra Rehman finds her profound interest in addressing the plight of Muslim women and their unappreciated marginalisation. Her focus remains on bringing a novel argument to life.