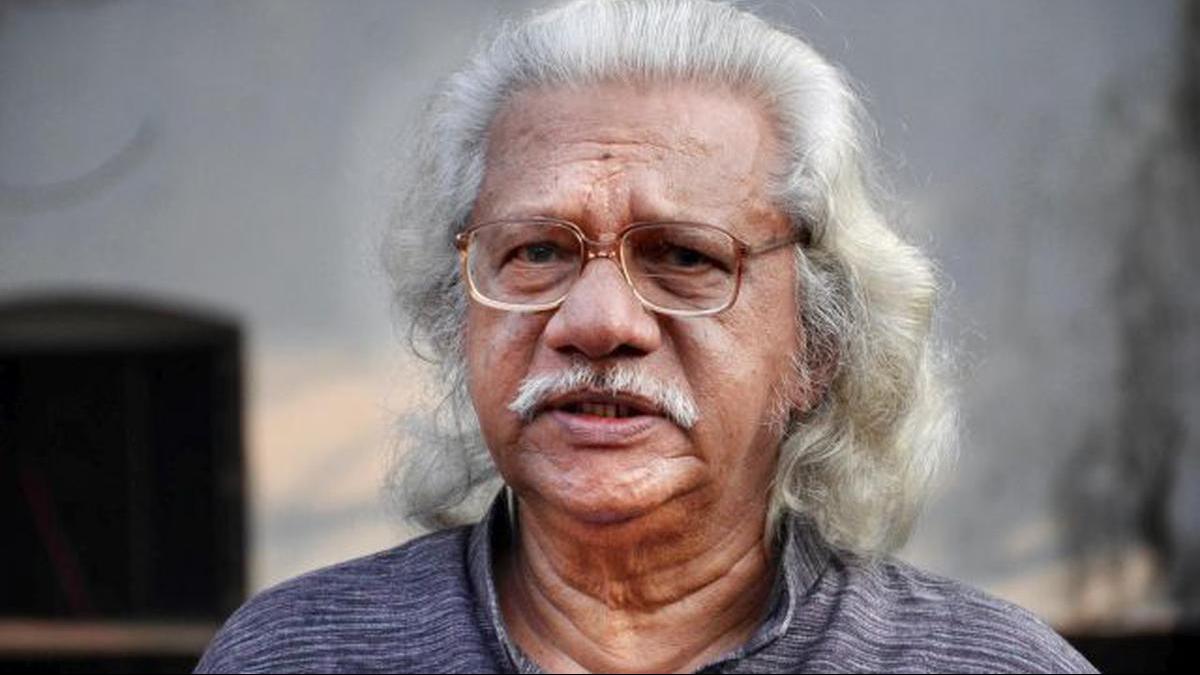

The two-day Kerala Film Policy Conclave hosted by the Kerala state government on August 2-3 to brainstorm regulatory policies for the state’s film industry ended in a fiasco when veteran filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan criticised the government incentive programmes for filmmakers from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (SC/ST) and women filmmakers.

Gopalakrishnan’s remarks drew instant censure from Malayalam musician and composer Pushpavathi Poypadathu. The incident has drawn Kerala film industry personnel into a protracted division along caste and gender lines. Dalit human rights activist Dinu Veyil filed a complaint against the filmmaker for promoting ill will against SC/ST communities under Section 3(1)(u) of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Gopalakrishnan’s remarks have displayed the full force of patriarchal and Savarna attitudes that contaminate the Kerala film industry.

Dalit filmmakers need “intensive training with experts”.

Addressing nearly 500 film delegates from around the country and the world at the Legislative Assembly complex in Thiruvananthapuram, Gopalakrishnan, in his concluding remarks at the conclave on August 3rd, insisted that the state’s current incentive programme is badly in need of reform, with many issues plaguing it, including corruption in the use of funds.

At the 13-minute mark of his speech, for nearly three minutes, Gopalakrishnan expounded on the shortcomings of both the Kerala State Film Development Corporation (KSFDC) incentive for SC/ST filmmakers and Dalit filmmakers themselves:

‘In my lifetime I have not made a film for two crores. At the same time, the government gives 1.5 crores to scheduled castes and scheduled tribes to make films. I told the esteemed minister that this will lead the way to corruption. The esteemed finance minister knows this. But no changes have been made. Also, when they are selected, I have an important recommendation to make. For these people from the scheduled castes . . . they should be given at least three months of intensive training on how to make films. Someone approaches (the state) with interest in filmmaking. Sending them away by telling them, “Go make a film,” is no way to encourage them. So, they should be given three months of training under experts. They should be taught everything, including how to budget for a film. . . These are public funds. This is tax revenue taken from the public. There are numerous very important issues in our lives that need to be funded. . . Yes, you must provide training to them. Reduce the amount from 1.5 crores for one person to fifty lakhs each for three people.’

Regarding KSFDC initiatives for women filmmakers, Gopalakrishnan reiterated his recommendations: ‘The funding for women is the same. Don’t give money just because somebody is a woman. A woman should also be given training. It is very important that we have women film directors. We have one or two, and they are good. But if we want new directors like them to come forward, they must understand the difficulties of making films.’

“Women filmmakers must understand the difficulties of making films.”

KSFDC, founded in 1975, started funding initiatives for women filmmakers forty-four years later in 2019-2020, followed by funding directors from the Dalit communities in 2020-21. Under the scheme, KSFDC awards 1.5 crores each to two filmmakers from each category. The applicants go through several rounds of evaluation, workshops, and interviews conducted by a panel of expert judges appointed by KSFDC.

Gopalakrishnan expounded on the shortcomings of the incentive for SC/ST filmmakers: For these people from the scheduled castes . . . they should be given at least three months of intensive training on how to make films. Someone approaches (the state) with interest in filmmaking. Sending them away by telling them, “Go make a film,” is no way to encourage them. So, they should be given three months of training under experts. They should be taught everything, including how to budget for a film‘

So far, ten films produced by KSFDC have been released and/or are slated to be released under this scheme, which include Nishiddho (Forbidden, Dir. Tara Ramanujan, 2022), Divorce (Dir. Mini I. G., 2023), and B 32 Muthal 44 Vare (From B 32 to B 44, Dir. Shruthi Sharanyam, 2023), and comprise directors from Dalit communities. Nishiddho won the Kerala State Film Award for Best Feature Film in 2022 with an international premiere at the Frankfurt Independent Film Festival, while B 32 Muthal 44 Vare won the Best Director Award in the Women/Transgender category in 2023, and Victoria won the FIPRESCI award for Best Malayalam Film by a debut director in 2024.

While Gopalakrishnan’s comments garnered some applause, audience response displayed several conclave attendees looking puzzled at these casteist and sexist remarks. At the outset of the public backlash against the filmmaker, the activist body Women in Cinema Collective (WCC) strongly condemned the filmmaker for his remarks: At the Kerala Film Policy Conclave and in the days that followed, Adoor Gopalakrishnan once again exposed his upper-caste, caste, and gender-biased perspective to the public through his comments on the filmmaking experiences of new female and Dalit directors in Malayalam cinema. During his speech, Adoor has undoubtedly confirmed his patriarchal and anti-Dalit stance by making derogatory statements about renowned singer Pushpavathi, who is also the vice-chairperson of the Sangeetha Nataka Akademi, who reacted against it. WCC strongly condemns Adoor’s approach and stance.’

“Who is she? Who has empowered her?”

In the aftermath of the incident, in an interview given to a prominent Malayalam news channel, Adoor Gopalakrishnan defended his remarks. He insisted that he was ‘speaking for’ the Dalit community and not against it. It appears that Gopalakrishnan has appropriated the right to ‘speak for’ the Dalit community to himself. He has no tolerance for voices from inside the Dalit community, as evidenced by his hostile and unprofessional tirade against Pushpavathi Poypadathu for ‘interrupting’ him during his speech. Referring to Pushpavathi Poypadathu at various times as ‘girl’, ‘that woman’, and ‘some woman off the street’, Gopalakrishnan barked at the interviewer:

.jpg?$p=a80322e&f=16x10&w=852&q=0.8)

‘A girl stood up and said something. She is a woman who has no connection to cinema. She is nowhere in this field. What right does she have to speak about this topic? She interrupted me while I was talking. People who were there made her sit down. . . What right do you have to interrupt someone while they are talking? How are you empowered for that? . . . I have worked in the cinema industry for sixty-plus years. . . Who is she? Some woman. She got publicity. That is the objective . . . You might know her, but I don’t. She is an unknown entity. She has no business there. She has no right to come to the film conclave. In what position is she there? Is the film conclave a place for any woman off the street to come in and talk? That too while I am talking. . . This is not a “chantha” (market). It is an important session.’

Pushpavathi Poypadathu is relatively well-known in the Malayali public sphere. A classically trained musician and the current Vice Chairperson of the Kerala Sangeeta Nataka Akademi, Poypadathu has composed and sung several popular songs for Malayalam films. As a musician from a Dalit community, Poypadathu has emphatically addressed ‘caste’ through her work as a musician.

Regardless of Gopalakrishnan claiming that ‘she is an unknown entity’, Pushpavathi Poypadathu is relatively well-known in the Malayali public sphere. A classically trained musician and the current Vice Chairperson of the Kerala Sangeeta Nataka Akademi, Poypadathu has composed and sung several popular songs for Malayalam films. As a musician from a Dalit community, Poypadathu has emphatically addressed ‘caste’ through her work as a musician. She has released several albums showcasing the work of progressive anti-caste thinkers, poets and saints, from Kabir to Tagore to Poykayil Appachan and Sree Narayana Guru, among others.

Poypadathu noted in an interview that if Gopalakrishnan does not ‘know’ her or ‘know of her’, that speaks to the filmmaker’s ignorance about Dalit matters. Poypadathu has also noted that as a Dalit musician she has struggled to find visibility and voice in the Malayali media landscape. She is well qualified to speak on the theoretical ‘difficulty’ of women and Dalit artists Gopalakrishnan mentioned.

Poypadathu maintained that she was compelled to speak out against the filmmaker’s recommendation that the state government reduce the 1.5 crores to 50 lakhs because it undermined the state’s attempts to redress years of inequity towards women and Dalit communities and bring them into the mainstream. ‘My morals have empowered me . . . I spoke with the rights I have as an Indian citizen . . . I felt compelled to speak right then and there when his remarks brought considerable distress to my brothers and sisters who I represent.’ Poypadathu responded in answer to Gopalakrishnan’s question, ‘Who is she? Who has empowered her?’

Pushpavathi Poypadathu is not the first person to ‘interrupt’ Adoor Gopalakrishnan at the film conclave. When Gopalakrishnan incorrectly cited ‘350’ as the number of films released in Kerala in 2024, a male voice from the audience corrected him with ‘230’. The filmmaker accepted the correction without incident. He reserved his anger for the Dalit woman.

Kerala Police will not pursue any legal action against the filmmaker, as his comments were not deemed derogatory to the Dalit community. However, this incident and its takeaways should inform any film policy in the making, as it asks to root out casteism and sexism at a just film industry workplace.