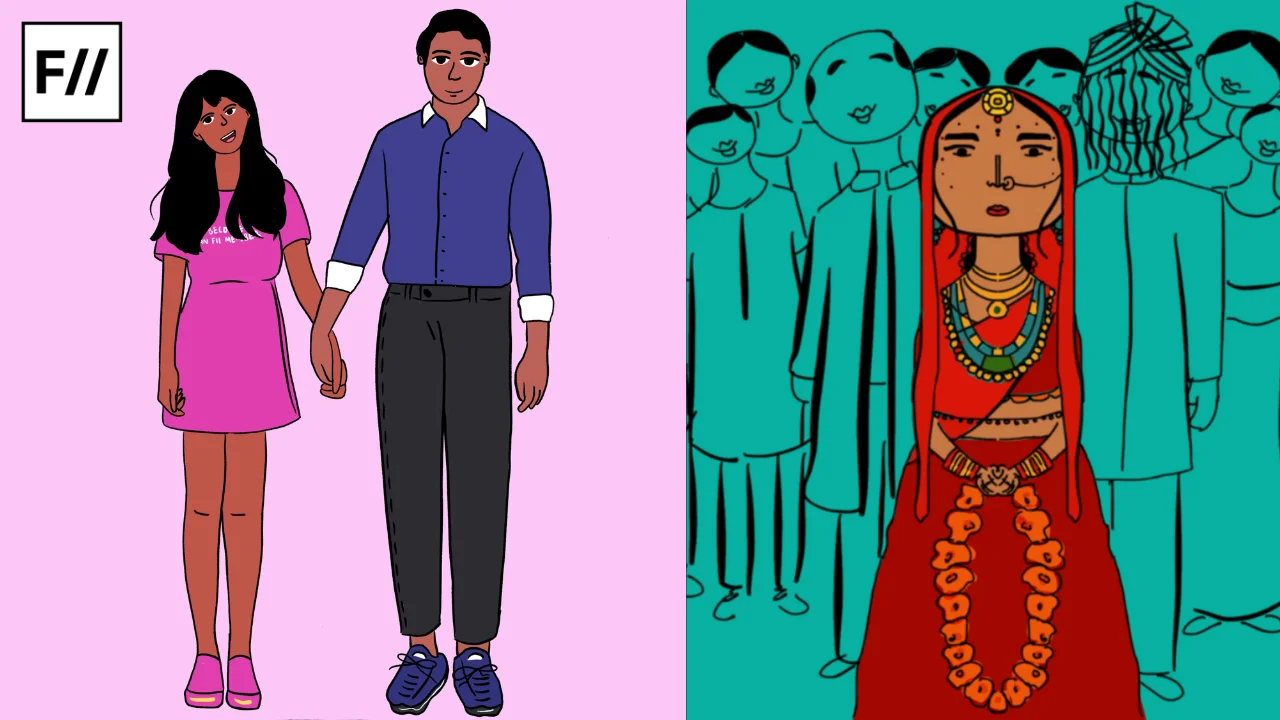

With 93% of marriages in India arranged and only 3% classified as love marriages, the country remains overwhelmingly oriented toward arranged unions. This is according to the 2018 Lok Foundation–Oxford University survey, administered by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), which covered over 160,000 households across the country.

Why is our society afraid of love?

On 27 January 2026, a panchayat in Panchewa village, Ratlam district, Madhya Pradesh, passed a resolution imposing social and economic boycott on families whose children enter love marriages or elope — no shared milk or goods, no work, no invitations, no social contact. The decree, which went viral and prompted police intervention with peace bonds, has reignited debate on why love marriages — especially inter-caste and interfaith — continue to face strong societal resistance.

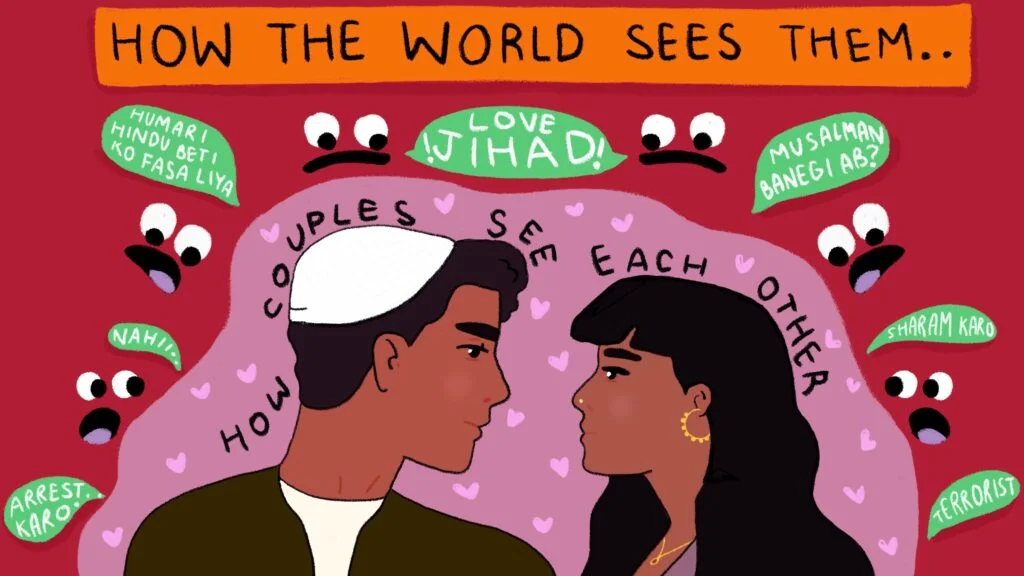

‘It’s because we as a society don’t want to come out of our comfort zones. There is a sense of hierarchy that is broken when people choose partners from different castes or religions. They are scared that their hard established belief system will break,’ says Priyanka, 25, from Jaipur. She is a Scheduled Caste Buddhist woman dating a Brahmin man from a conservative family. He is the only son of his conservative parents.

‘Even our friends assume beforehand that we will not marry because it’s not possible. We often assume that this mindset goes away with education, but it’s not true. People in the so-called elite and intellectual circles have called me a boy trapper. They have circled my boyfriend and told him, “Date her if you want, but you can only marry a brahmin girl,”‘ added Priyanka, a media professional.

Harsh Malhotra, team coordinator of Love Commandos, an NGO that supports couples facing resistance, agrees with Priyanka. ‘I remember the case when a couple, an IAS and an IPS officer, came for our help. They were so confused because of the harsh resistance they were facing from their families that they didn’t have any option left. You like love and romance in movies. But when your child chooses love, you want to kill them. For that child, the parent becomes the villain.’ Harsh said.

Despite Supreme Court rulings in Lata Singh (2006) and Shakti Vahini (2018) that protect consenting adults from violence and coercion, love marriages — particularly inter-caste and interfaith — continue to invite ostracism, confinement, and, in extreme cases, honour killings.

This kind of policing — subtle in cities, overt in villages — shows how deeply entrenched endogamy remains. Despite Supreme Court rulings in Lata Singh (2006) and Shakti Vahini (2018) that protect consenting adults from violence and coercion, love marriages — particularly inter-caste and interfaith — continue to invite ostracism, confinement, and, in extreme cases, honour killings.

When young people fight for love

Sanjana Kumari, 29, a native of Bihar, was locked inside her home in 2022 when her Kurmi family discovered her relationship with Suman, a Yadav man living across the street. ‘My phone was snatched, I was not allowed to eat for days,’ she recalls. ‘I felt unconscious. An aunt helped me escape from the rooftop.’ The couple eloped and married three times — each time without their parents’ blessings.

The first marriage took place in a hotel right after they fled, so the hotel owners wouldn’t suspect them. The second was on Shivratri, as they wanted a proper anniversary memory after the rushed elopement. The third was during Teej, simply to mark the festival together. They lived apart for years — Sanjana in Patna, Suman in his village — lying to landlords and neighbours about their relationship. ‘Society is harsh towards eloped couples,’ Sanjana says. ‘No one likes a marriage without parents’ consent.‘ Only after Suman’s father died and they had a son did they finally return home.

This harshness takes a community level form in extreme cases, says Asif Iqbal, founder of Dhanak of Humanity, another NGO that supports love and couples who fight for it. He remembers an incident in Raigarh, Odisha, where an entire community was removed from the NREGA list because of an intercaste marriage. He believes women often face more restrictions. Their families first try to snatch their financial independence if they have a job or education, locking them in their room.

Sometimes a couple may have acceptance from their immediate family, but this still can’t save them from society’s judgment.

Dimple, a 29-year-old PhD researcher, married Romain, a French national she met on social media. After a year of a long-distance relationship, they met in person in 2023 and are now married.

Dimple, a 29-year-old PhD researcher, married Romain, a French national she met on social media. After a year of a long-distance relationship, they met in person in 2023 and are now married. While Romain’s family welcomed her warmly and her own parents accepted the relationship relatively smoothly—glad she could express her authentic self—relatives were far less supportive. They criticised her for ‘wasting her potential‘ as a scientist by choosing a chef as a partner, and some remarked that ‘too much education ruined her‘ and that she was ‘bringing shame by marrying a foreigner.’ Online trolling followed, with hateful messages from Indian women flooding her DMs. Dimple believes the backlash stemmed from a desire to “protect their culture” by stopping her.

Reflecting on the broader hesitation toward love marriages, especially intercultural ones, she says India remains a performative and hierarchical society that breeds superiority, entitlement, and an illusion of control. This mindset, visible in resistance to inter-caste or inter-economic unions, translates into families where individuals accept traditional frameworks as unquestionable truth. Those who choose to live unconventionally often face judgment, even when immediate family issues are resolved—society’s disapproval persists.

Between love and hope

Yet, amidst all this hesitancy, uncertainty, and chaos, hope persists.

Rajesh Mishra, marriage coordinator at Neeli Chhatri Mandir, performs love marriages under the Hindu Marriage Act after verifying both partners are adults. ‘We marry them according to Vedic rituals. We perform the haldi ceremony, kanyadaan, phere, and give blessings,‘ he says. ‘But trust issues and fear of social boycott are the biggest hurdles. Parents are angry. If they are in a live-in, why can’t they marry? Society is harsh,’ adds Rajesh.

‘You can’t stop love,’ says Asif Iqbal. ‘If you try to stop it forcefully, in the name of caste, class or religion — it will still happen. Love will find its way.’