Sita’s Family, a documentary made by Saba Dewan, is a tour of her family history. On the surface, it is a simple account of Sita Devi and Chabil Das’ involvement in the Indian freedom struggle and mostly of Sita Devi’s active political life until her death. But it also shows the side of the story that is often ignored when discussing the lives of famous political figures – the domestic narrative.

Considering the scarcity of women being celebrated for their involvement in Indian freedom struggle or any kind of revolutionary politics, where they aren’t seen as a secondary support to a man (as wives, sisters and daughters), the documentary raises valid questions about the expectations of society from a woman as a mother, wife, daughter inside the house and a ‘professional’ outside the house.

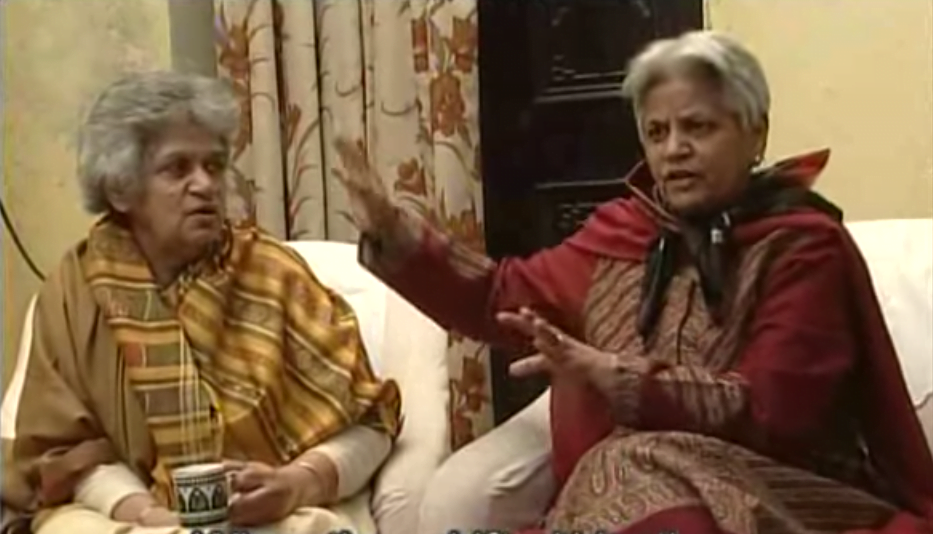

Sita Devi, as narrated by her grand-daughter Saba Dewan, was a campaigner against colonialism, for women’s rights, and a trade unionist. She was also an elected member of the legislative assembly. When the whole family gathers to discuss and analyse their past, fragments from multiple stories from her daughters and son gives the audience a picture of Sita Devi.

Manorama Dewan, the narrator’s mother talks about 1942 Quit India movement when her mother Sita Devi was arrested for her involvement in it. Manorama, who was a child, was also taken along – she vividly recounts the life of women inside the prison cell. She remembers her mother’s housekeeping skills and how she would decorate the prison and save up milk to make kheer. Another incident that is mentioned by the family is the hoisting of the Indian Tricolour in the women’s prison while women sang songs of resistance. Different women asked for saris in saffron, white and green and stitched several Tricolours together and then pulled off the Union Jack.

Apart from several anecdotes from the independence struggle and people marching up to Sita Devi to request her involvement in dowry and murder cases in neighbourhood the documentary delves into the personal consequences of her involvement in active politics. While some of the daughters understand Sita Devi to be their role models, some don’t.

This question of the division of a woman’s time and labour between maternal care and career runs through future generations too. Some women in the family chose to dedicate their labour to childrearing, owing to the sense of detachment and strain they felt over the absence of their own mothers in their lives. Sameera, the narrator’s younger sister, left her career to take care of her daughter but it also left her under-confident and depressed. This, as she confesses, came from a sense of under-utilised potential.

To this accusation, Manorama Dewan asks questions from her daughters: why did they assume that emotional labour was to be her responsibility only? She says that a woman has to fight on many fronts. Manorama Dewan asks her daughters if they had ever seen their father help her with household work, and why they didn’t expect their father to carry the weight of their emotional welfare and support like staying up for the children’s exams among others. She mentions that it is always expected of women to make sacrifices and that certain things, like helping the male members of the family with their ambitions, are taken for granted from women. In these cases, the ambitions and aspirations of the women get invisibilized. She mentions wistfully that she would have liked to be a part of active politics like her mother.

Also Read: House Work? What’s That? Caregiving And [Un]Paid Work

Sita’s Family brings us the stories of women who are absent from the dominant narratives of freedom struggle and politics. Going deeper, it also explores the consequences of expectations from women and how women themselves internalise the roles and functions of emotional labour, child-rearing and housekeeping assigned by the society.

Given the state of contemporary (self)-fashioning of women in politics as “Mothers”, we need to ask the question if this is the only way that a woman’s presence can be legitimized, and how fair we really are to our ‘mothers’. Does this title of ‘motherhood’ suggest that the totality of the concerned person’s time and energy will be spent on taking care of her ‘children’ i.e the voters? The dominant strain of strong, influential and politically strong women as self-effacing and hence, powerful “Mothers” leads to invisibilization or erasure of association of power with any other persona or role of a woman. As a result, the ‘ideal’ motherhood and the qualities associated with it haunt the women stepping out in public life.

About the author(s)

Richa Thakur is a literature student who reads people and books wherever she goes. Researcher and experimenter by technique, she is currently concocting formulas to fight all kinds of patriarchy.