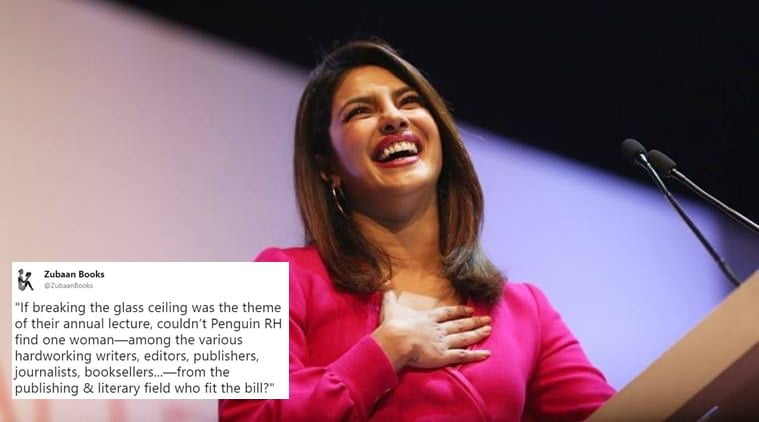

rOn Boxing Day of 2017, Priyanka Chopra delivered the keynote address at the eleventh edition of The Penguin Annual Lecture.

The anomalies in that sentence have already been pointed out by some, but in 2017, a true annus horribilis for women, in which perhaps the only silver lining was the relaunching of the #MeToo campaign, it was an incredibly tone-deaf decision by a renowned publishing house that really, really ought to have known better.

In the eleven-year history of the lecture that intends to ‘bring writers, artists, thinkers and key personalities’ together for ‘readers, book lovers, and the youth’, I could not find any evidence that any woman other than Priyanka Chopra has ever spoken at this event as a keynote addresser. I found the names of Amartya Sen, Ramchandra Guha, Dan Brown and even His Holiness the Dalai Lama in the announcement made by the publishing house. If there ever has been a woman speaker, there was no mention of her.

It beggars belief that the company with the likes of Arundhati Roy, Kiran Desai and Jhumpa Lahiri on their roster, in addition to all the women employed by their various departments including that of social media, and a woman – Hemali Sodhi – at the helm, could not find a single woman they deemed worthy of delivering the address. Why, then, choose a woman who has nothing to do with the publishing industry, who has never published or contributed to a single book in any substantial capacity whatsoever? Why choose a woman who is hyper-visible, thus doing a disservice to the invisible labour of all the women in all these roles of publishing we do not find out about?

The decision is symptomatic of women’s continuous struggle with the politics of visibility and invisibility that determines who is allowed to be at the centre and who at the margins. In most societies and nation-states, it is determined by existing socio-cultural power structures – in the case of India, the cis-het-upper caste-upper class nexus. Penguin Random House India’s choice of speaker, possibly the first woman to ever speak at this lecture that touts itself as ‘one of the most prestigious and eagerly awaited cultural events on the calendar’, does nothing to undo any of these.

As a publishing behemoth existing in the contemporary socio-cultural fabric, it has every responsibility to do so, especially if it chooses ‘Breaking the Glass Ceiling’ as its topic. The responsibility lies not merely towards the authors, the most visible participants in the industry, but the other women providing labour in the capacity of commissions and copy editors, subeditors, proof readers, graphic designers, illustrators, photographers, social media managers and dozens of other roles, as this article in Scroll points out, smashing through glass ceilings every day.

This pushback is not a Priyanka Chopra v/s ‘other women’ issue; it is not aimed at her occupation of being an actress and nor is it, as I mentioned on my Twitter profile, about the creation of some sort of a false beauty/ intellect binary. Nobody can deny Chopra’s professional accomplishments, or the fact that she has been successful in her field. But surely the very fact that nobody will deny only serves to illustrate my point: everyone already knows. The politics of visibility/invisibility is still at play, and without negating her considerable personal achievements, one can acknowledge this and choose not to propagate it. That Penguin Random House India failed to do so is their failure and not hers, at least not in full or as completely.

But Chopra is also, undeniably, a privileged savarna woman who has found material success in a field that is glamourised in the country and confers immense cultural capital and access to her. A series of tweets pointed out how the only book by a woman that Hindustan Times included on its ’10 Books We Want to Read’ was by Twinkle Khanna, in a year that expects to see the release of books by Snigdha Poonam, Anuradha Roy, Shanta Gokhale, Shrayana Bhattacharya and the young Gurmehar Kaur – and these are only the few that I do know about and excluding dozens of queer and Dalit women whom I know criminally little about.

It’s time for women who don’t have this capital to share the space that so many other women like Chopra occupy, especially when the topic is to do with breaking specifically gendered systemic barriers that hold women back. The decision to not do so sends the message that in order to be validated as a woman who has broken the glass ceiling, one needs to have this kind of cultural capital and access – otherwise, they can prepare to be overlooked.

To bring the other men who have delivered the lecture in previous years into this conversation is futile, because this discussion is about women’s labour and the invisibilization of it, which renders their participation irrelevant except in the context of how it persisted in furthering the patriarchal narrative. It’s worth noting that every man in the past who has delivered the lecture has had a literary connection. This includes the example everyone keeps turning to, to argue that people from the entertainment industry have participated before: the actor Amitabh Bachhan, who delivered the lecture in 2013.

When I protested against this decision on Twitter, journalist Vir Sanghvi took it upon himself to defend the decision and, by extension, some sort of attack on Priyanka Chopra’s honour that he had imagined the protest to be. HarperCollins India’s CEO Ananth Padmanabhan and Penguin Random House’s Editor-in-Chief of Literary Publishing, Meru Gokhale, ‘liked’ his tweets written in response to mine, without engaging with me, sending a clear, albeit passive (aggressive?) message: his inability or unwillingness to listen to and comprehend my stance was more important and more valid to these industry stalwarts who hold the futures of so many women writers and industry professionals in their hands – professionals who are now a little more convinced that their way to the visible centre just became a little more inaccessible then it already was.

I know that not everyone in the industry agrees. Zubaan Books tweeted a series of very pertinent points on this issue that express very articulately, from the point of view of a dissenting peer, exactly why this move was so objectionable.

Raghu Karnad tweeted the Scroll article mentioned earlier, adding in a later tweet, “The real glass ceiling: the idea that women are only of public interest if they’re beauty-queens or actors.” Writer and political commentator Devdan Chaudhuri put up a Facebook post questioning the reasoning behind the move. Huffington Post India’s Senior Editor, Somak Ghoshal, commented, “It’s not unfair to expect that an annual lecture organised by the biggest publisher in the country would be an occasion for setting standards of literary excellence … Saying Priyanka Chopra isn’t the ideal candidate for delivering a literary lecture does not mean she’s unqualified to speak about breaking glass ceilings. On the contrary, she is eminently suited to speaking on the topic, but perhaps in a different context and occasion.” I even spoke to someone who was involved in the organization of the event, who mentioned that they did not agree with the choice of speaker and neither did many others involved with the event.

Why, then, was this decision taken? What was the rationale? Was it a question of glamour, that cultural capital that Bollywood encashes? Do we even begin to consider the larger implications of Bollywood as an industry and how systemic discrimination against women plays a part in it, in the context of this decision? And what do we conclude about a lecture that features a woman as a speaker, perhaps for the first time ever in its more than a decade long history, and in the process chooses someone that has contributed nothing to the field, the people and the establishment that organized it?

Does the word ‘tokenism‘ come to mind?

2017 was the year of redemption for women in the long, bitter struggle to be heard. What an unfortunate note to end it on.

Featured Image Credit: Indian Express

About the author(s)

Rushati Mukherjee is a Producer of the news podcast BBC Minute India, for BBC World Service. They have written for national and regional outlets as a freelance Features journalist. They are on the Advisory Board of the British Council's international journalism conference, Future News Worldwide. They are also a translator and a poet, and have been an official blogger at the Jaipur Literature Festival. They can be reached at @rushatim on Twitter.