Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.

Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.Sensationalism has become the media’s preferred route to discuss the important issue of gender-based violence (GBV). GBV has become a tool to grab eyeballs and get higher TRP ratings, contributing to the rape culture and a sense of apathy among people. Only the most brutal violence is considered worthy of getting reported. It sets up the notion of “more violent” and “less violent” crimes against women, resulting in creating new criteria within the minds of people about what should and shouldn’t be considered as harassment.

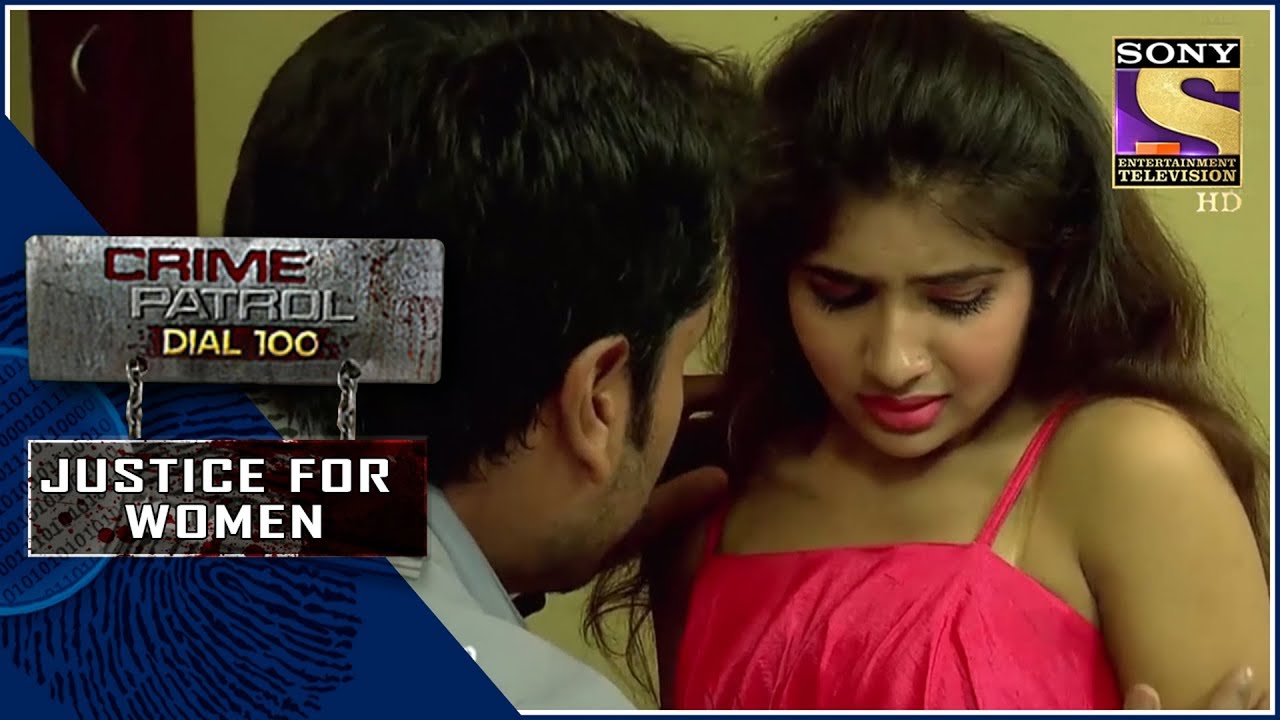

There are certain TV shows which have taken sensationalised reportage to the next level, by retelling GBV cases in a theatrical manner. Shows like Crime Patrol, Savdhaan India, Gunah and Sansani have made a fortune out of turning trauma into entertainment, and making a mockery of these cases under the guise of ‘awareness’ or ‘gender sensitisation’.

Also read: Why Are Sensationalist Headlines Of GBV Cases A Problem?

Crime Patrol and Savdhaan India are famous Hindi TV shows that showcase criminal cases (both imaginary storylines and real cases) and focus on how to prevent these crimes. Their aim is ostensibly to spread awareness. Gunaah is an online show which focuses on sharing tales of crimes committed and how people can seek revenge. Sansani is a news show which often shows news reports in a theatrical manner to explain the crimes.

Depiction of Women: Either Victims or Vamps

If one analyses these shows, they will be able to find a typical set of stereotypes. Women are either helpless victims who are too naive to understand that they are in danger or cunning vamps who boldly speak out and “provoke” the criminal into committing a crime. Both of these stereotypes are commonly used in victim-blaming. Women are often criticized for not being shrewd or careful enough to avoid sexual violence, or alternatively being too outspoken in a way that invites violence. These characterisations are used to minimise the impact that sexual violence can have, by implying that the women deserved it or “should have known better”, and should now deal with the consequences of their actions silently.

these shows have made a fortune out of turning trauma into entertainment, and making a mockery of these cases under the guise of ‘awareness’.

When not victims, women play the role of villains. These villainous women are either sex-starved succubi, or so madly in love with a man that they would go to any length for him – for example, the murder of in-laws to run away with the boyfriend. Another common trope is that of women being the evil masterminds and innocent men being manipulated by these women to commit their crimes for them. It reinforces the “aurat he aurat ki dushman hoti hai” (women are women’s worst enemies) mentality among the masses and removes any sense of responsibility and accountability from the men who are equally involved in the crime committed, placing the blame squarely on women’s devious sexuality.

The Gunaah episode above displays a case of cyber crime, where a woman is blackmailed with the leaking of her private videos. And yet, the tone focuses on how people should not make online friends, form online relationships or have video chats. The episode seeks to blame the victim rather than focusing on the crime done to them – the narrator uses the phrase “her mistake” to refer to the woman being trapped in this cycle of blackmail. The woman is shown as the naive and helpless victim who got fooled by a greedy blackmailer. She ultimately kills herself – a common occurrence in these shows that feeds into the narrative that victims of sexual abuse are better off dead than to live on with the “dishonour”. The story also shows another woman in a the classic sexy, manipulative vamp character who makes the blackmailer confess his crime by deceiving him, and takes revenge by infecting him with HIV, furthering the stigma against HIV positive people.

Catering To The Male Gaze

These shows – both in their storytelling and their camera angles – cater to the male gaze. GBV is shown as something is happening to a woman (a helpless victim) rather than something being done by a man. The woman, who is fetishised and objectified, is the focus of the show, while neither the perpetrator nor the systemic nature of GBV captures the same amount of attention.

If one sees Kandivali Murder Case’s depiction on Crime Patrol, the thumbnail shows a naked woman covering herself with a blanket. These scenes are often used in promos to grab eyeballs, further dehumanising and sexualising women – turning gender-based violence into a sexy incident.

Depicting crimes against women as something “sexy” or “hot”, is problematic on so many levels. It dehumanises women and their abuse. It normalises sexual violence and tells men it is okay to harass women as it is sexy. Showing gender-based violence from an erotic angle is counter-productive to what shows like Crime Patrol and Savdhaan India state as their intention. Instead of raising awareness, it causes further misinformation about gender-based violence as something that women “provoke” by being “too sexy”.

Crime Patrol often tries to focus on the “why” of a crime, focusing on the criminal’s thought patterns and advocating mindless victim-blaming. The causes are viewed as individualised crimes of passion, not as a systemic issue that is rooted in patriarchy – it is seen as sexual, not social. Gender-based violence is about enforcing power and sex is used as a tool to do so. Instead, these shows focus on showing it as an outcome of the “uncontrollable lust” of men and women being “careless”, which further shifts the blame of crime to the victim instead of the abuser.

These depictions can also be excessively triggering to viewers of the show that have experienced GBV.

Justification Of Perpetrator’s Actions

Mainstream media, while reporting gender-based violence, often uses words like “Romeo” or “lover” to describe stalkers who are harassing women. This minimises the gravity of the crime and also justifies the actions of the perpetrator. The TV shows highlighted in this article also do the same – often painting criminals in a sympathetic light by asking questions like, “How can a person like him do this?”, “What makes them do so?”, “How are they changing and becoming criminals from being nice?”, etc. By portraying these perpetrators as “nice men” who turned violent on this one occasion, this shifts the blame onto the victim for “converting” a nice man into a criminal.

Romantic rejection is often used as an excuse for gender-based violence, and becomes yet another way to blame victims for causing the violence by either getting involved with the man in the first place, or for turning him down. These shows highlight that the perpetrators were eyeing the victim for a long time, and the victim ‘encouraged’ this interest by being friendly. Sometimes basic kindness displayed by women is viewed as a “seductive gesture”, causing the perpetrator to fall for the survivor, and later harm her.

Another common trope is the background of the perpetrator being used in his defence. If he has done something extraordinary in his life, it is mentioned over and over again, as though to highlight how unbelievable it is that this crime is true. This valourisation of perpetrators often stops victims from reporting crimes as they are told over and over again that they could “ruin his life” by complaining.

Also read: The Spectre Of False Rape Cases And How The Media Perpetuates It

Shows like Crime Patrol, Sansani, Savdhaan India and Gunaah attempt to spread awareness about gender-based violence, but succeed only in reinforcing victim-blaming and minimising the trauma of gender-based violence by turning into a theatrical gimmick for higher TRP ratings. These depictions can also be excessively triggering to viewers of the show that have experienced GBV. These shows remove the accountability on the perpetrators by focussing obsessively on the victims and their behaviour patterns, further reinforcing patriarchal notions like the surveillance of women to ensure that they “avoid” gender-based violence.

This article was written in consultation with Asmita Ghosh, the lead researcher of the #GBVinMedia toolkit.

Featured Image Source: Live Uttar Pradesh

About the author(s)

Meghna Mehra is the first asexual student leader of India. She is author of the book Marriage of Convenience and founder of All India Queer Association. A graduate in political science, she understands social issues from a gendered perspective.

I’m watching regularly crime petrol??