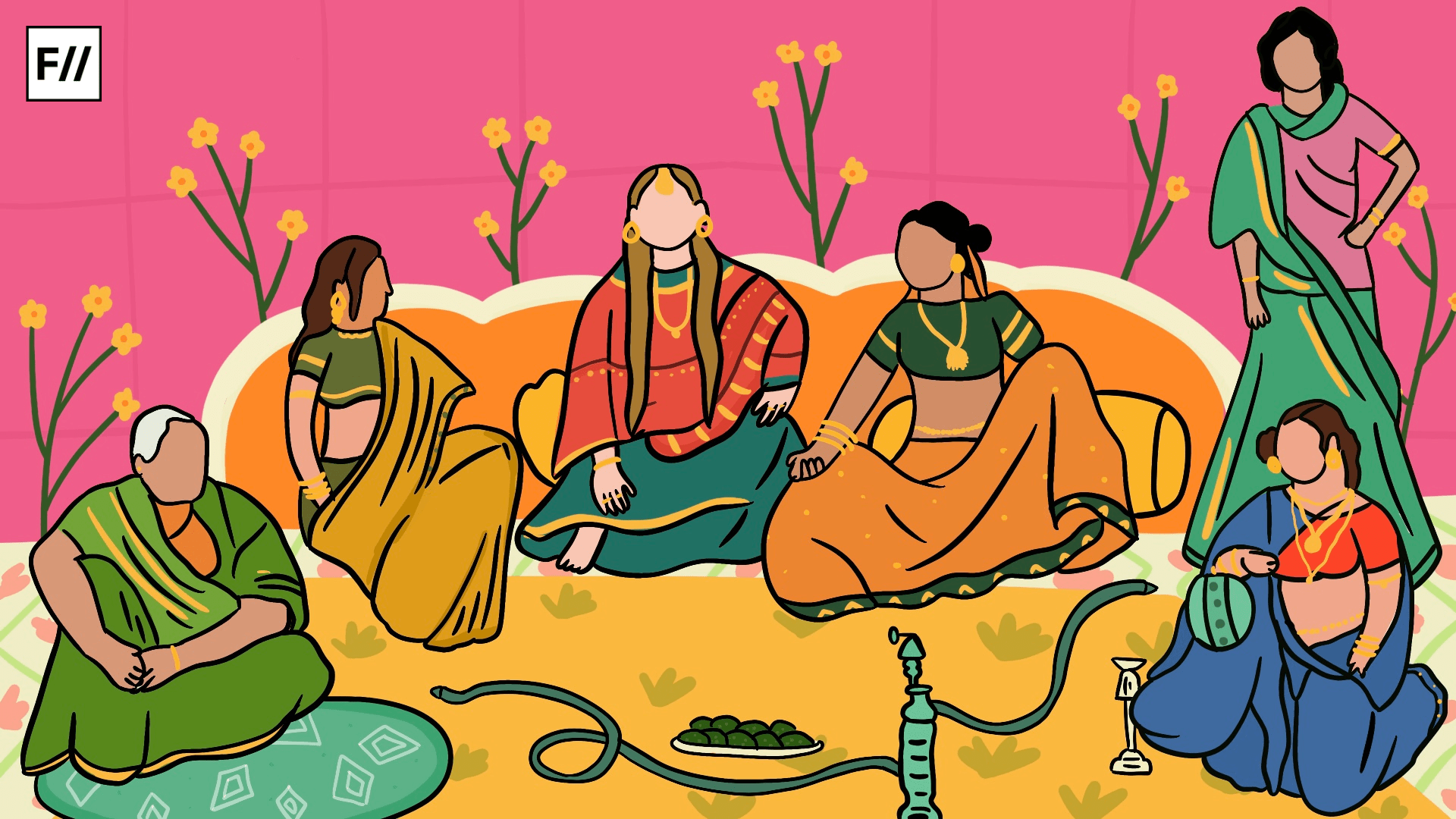

In this essay, I have attempted to reconstruct the history of ordinary women in the everyday life of the Mughal empire. It is necessary to remind ourselves, time and again that a whole category of gender cannot be just represented by writing about the popular imperial princesses. No matter how interesting their lives had been, history does not only belong to them.

For a gender-based analysis of the period, it is important to have an intersectional approach to look at the Mughal empire. We find reflections of the other gender apart from the within the imperial court of the Mughal empire only in passing but they seemed to have formed a major portion of manpower who exercised their role through the ambiguities of the system. Their role cannot be defined in a clear-cut manner as what happens in modern society. There is a need to study this subject by not locating gender as an isolated entity but interlinked with other social differences.

For a gender-based analysis of the period, it is important to have an intersectional approach to look at the Mughal empire. We find reflections of the other gender apart from the within the imperial court of the Mughal empire only in passing but they seemed to have formed a major portion of manpower who exercised their role through the ambiguities of the system.

Popular belief, if not serious scholarship, maintains the position that position of women in medieval Islamic society was an extremely depressed one. Women were secluded to harems and supposed to have no public life or pursue of economic occupations. Famous scholar Ronald Jennings questioned the universal applicability of this theory in the context of Ottoman Empire. Similarly, in India’s Mughal empire, efforts have been made to generate lives of women from a new perspective.

Also read: 4 Women Who Ruled Over The Mughal World

Although the availability of sources is always a limitation when it comes to generating lives outside the court and the imperial family. The sources which could help carry out a research like this are paintings and legal documents.

With a careful historical analysis of sources like paintings where we come across certain ordinary women characters and a careful reading of Persian texts, we are introduced to the kind of activities ‘middle class’ women were involved in. A significant point which the historian Shireen Moosvi makes, in her article, The world of labor in Mughal India, is that from the pictorial depictions it can be deduced that the division of labor by gender was all-pervasive, even within the same occupation, for instance, woman as a spinner and man as a weaver.

This shows that more intense activities were usually undertaken by women in the Mughal empire. Women were also employed in other crafts and professions. These are likely to vary along the lines of class, caste, locality and with changing relations of production and distribution, gendered aspect to it which is not usually analysed.

There are also instances of women in the Mughal empire holding immovable property including residential and agricultural land, gardens, etc. However, there is a need to ask better questions, for instance, what kind of property they held and in what ways? Did they actually wield the power to control and manage the property or were they proxies?

Scholar Bilgrami Rafat‘s work on the ‘Property Rights of Muslim Women in Mughal India’ helps us explore these questions. There are majorly three factors determining the answers to these questions. Firstly, the question of the inheritance of a division of property. By law, Shariah provides inheritance rights to women, in which a portion of the natal property goes to the daughter as well but sometimes it happened through joint rights over the property, in that case the right was not very well translated.

Here, evidence shows women exercising this right to inheritance. In some cases where the right has been denied, women appealed to the court to file the case. The wives’ share left by their husbands has also been recognised. In a case, the wife inherited all the property which the husband himself had bought in the Mughal empire.

Secondly, the provision of claiming dower called as mehr. Mehr is an Islamic practice and a precondition to marriage. Banarasidas’s Ardhakathanak, which is his autobiography written during the Mughal empire period, offers evidence of mehr in the form of property. The mehr is of two kinds, which is Mu’jjal and Mu’ajjal. The former is paid in full at the time of the marriage ceremony, and the latter is delayed, usually paid in installments, but is tagged with the demand (indu”tlalab) it was expected to be paid whenever demanded.

Finally, there is evidence of women members receiving gifts of property in the Mughal empire. A bestowal deed (tamlik nama) was prepared to protect the property of daughters and other women from encroachment by some male members of the family, notes Bilgrami Rafat. Sometimes mothers made out their entire properties to a child or some members of their families. The possible reason for such a transaction was that she did not want children of other wives of her husband to encroach on the right of her only daughter.

It was not just the ownership that was credited to women but there are many examples of women proprietors selling land and other property which means they had control over the land also in the Mughal empire. However, as scholar Bilgrami Rafat in his works on property rights of Muslim women in Mughal India mention, this was done basically through the services of a wakil or by any male member of the family.

It was not just the ownership that was credited to women but there are many examples of women proprietors selling land and other property which means they had control over the land also in the Mughal empire. However, as scholar Bilgrami Rafat in his works on property rights of Muslim women in Mughal India mention, this was done basically through the services of a wakil or by any male member of the family. Women were usually represented by wakils even when filing a case at the court but they could carry the cases to the court if their rights have encroached.

In the case of the management of female property, it was undertaken by males for one the following three reasons – joint holding, women were observing purdah and therefore could not move in public, women were illiterate and it was difficult to cope with the documents. As Yasmin Angbin shows, not all women in the Mughal empire were illiterate though, since there had been professions like nurses, scholars, and poetesses which occurs in sources and therefore, says something about their education.

Also read: Zaib-un-Nissa: The Gifted Mughal Princess | #IndianWomenInHistory

Mughal social history can only be understood by locating the roots of the normative social constructs that flowed throughout the empire. The imperial device to identify political authority and social honor in terms of court and courtly ethics formed the masculine identity of the period of the Mughal empire. “Gender identity and norms became important in the political and religious discourses of Mughal north India where the meaning of manhood ran through these discourses with their antecedents in wider world of medieval Perso-Islamic political culture, constructing important links between kingship, norms for statecraft, imperial service and ideal manhood”, quoted from Ruby Lal’s Rethinking Mughal India: Challenge of a Princess’ Memoir.

On a concluding note, an important take away from reconstructing the everyday Mughal life is to assert on the articulation of women’s agency, fogged by the ambiguities of a patriarchal system.

References

- Moosvi Shireen, “The world of labor in Mughal India”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 71 (2010-2011), pp. 343-357, Indian History Congress

- Lal Ruby, “Rethinking Mughal India: Challenge of a Princess’ Memoir”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Jan. 4-10, 2003), pp. 53-65

- Yasmin Angbin, “Middle-class women in Mughal India”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 75, Platinum Jubilee (2014), pp.295-306.

- BilgramiRafat, “Property Rights of Muslim Women in Mughal India”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 48 (1987), pp. 261-270.

Sony Sachdeva is a student of medieval history in Delhi. Apart from studying how to write history, she wants to work for an inclusive and progressive education system in India. Sony is passionate about indulging herself into new skills like learning a new language or picking up basics to make a mini documentary to grow richer with new ideas and independent thinking. She can be found on Instagram and Facebook.

In India for ages women used to be the part of work force. Women from farmer families used to undertake number of activities of farming. Similarly other craftsmen were assisted by Women folk in the families. Nearly all of them used to assist their family men Husbands, Fathers , brothers or other family men. Exception was ladies from.landlord families or brahmin priest families. However ladies from.Brahmin priest families used to help organise the activities and do background work needed to perform puja and other rituals. Ladies from.the landlord families were responsible for monitoring the house staff and ensuring a proper hospitality for the guests and visitors.

The young girls of he families used to be trained in the support roles of the family trade and hence used to be skilled womanpower for their husband’s families. I believe that is the reason same cast marriages were the norm. As a carpenter family girl used to be trained for carpentry support work like painting and polishing and was ready to contribute to her carpenter husband’s profession.

Also in most of India, these trades including farmers tilting the land, a man’s family has to pay the money to girls family. Dowry according to me was restricted to land lord families only.

This system continued thru out Mughal, British and initial years of Independence till the time agriculture based village economy was dormant. Urbanisation and dilution of ,agri based and self sufficient village based economy changed this.

More research will throw the light on this.

It’s not moghal way of dressing

Here is a painting of Mughal emperor Babur (left) seeking advice from his grandmother Daulat Aisan Begum (right).

Observe the costume of Babur’s grandmother. This was the original Mughal costume.

It is a MYTH that Hindu costume of North/North Western India owes to Mughals. https://t.co/XM4QdSvWSA

Hi, really nice to see this article and the approach taken. Your thoughts are interesting and should be followed further. I recommend having a look at

Gender and Travel Writing in India, c. 1650-1700

Prasun Chatterjee

Social Scientist

Vol. 40, No. 3/4 (March-April 2012), pp. 59-80 (22 pages)

Published By: Social Scientist

An interesting read. Thankyou you for an insightful article as this.