This is the story of how I have been living as a woman with an invisible illness, a chronic autoimmune condition in India. I’ve been living with type 1 diabetes since the last 25 years. People like us need to take 4-6 insulin injections daily and test blood sugars on a glucometer 5-7 times daily, simply to be able to survive for the rest of their lives. Blood sugars too high or too low could kill pretty quick (no kidding!). Thanks to a partly dysfunctional pancreas, type 1 diabetes patients literally have to ‘be’ our own pancreas, 24X7X365. It’s not easy, to say the least. If you’d like to understand the different types of diabetes, see this video or read this article.

If you thought that was the tough part, wait till you hear more. Gender bias and sexism predictably rear their heads in this scenario too. Women’s health concerns are more often than not dismissed by healthcare professionals as simply a result of them being over-anxious, hyper and are often told that “it’s all in your head, just do some yoga and sleep well”. Needless to say, health disparities do not just affect people based on gender, but also caste, class, age and sexuality.

Exercise is important for everyone but it’s especially a great tool for people living with an invisible illness such as any kind of diabetes too. Diseases do not differentiate by gender, however, gender differences exist in exercises too.

Also read: Living With Chronic Illness And Its Lasting Impressions

To a large extent, general health and wellbeing is greatly impacted by the upkeep one puts in. Exercise is important for everyone but it’s especially a great tool for people living with an invisible illness such as any kind of diabetes too. Diseases do not differentiate by gender, however, gender differences exist in exercises too. For a long time I was very conscious of how I looked when I went out for a jog, “Were my shorts too short?”, “Too orange maybe?”, “Are my legs too hairy?”, “Will I get letched at if I wear the sleeveless or racerback top?” (rhetoric sis, of course I will).

I am pretty sure these are thoughts that probably do not occur in most men’s minds. The common understanding is that exercise for women should be feminine for them to stay ‘thin and pretty’, like dancing or yoga perhaps? I do not mean to imply that these forms of exercise are not okay, if you like it, just do it. But why assign a gendered association with exercises, you know?

For instance, when I announced I wanted to run a (42km) marathon or do a 100km trail walker, a lot of people looked at me in disbelief. I did it anyway, of course. Years ago, at work my colleague introduced me to a client and after introducing me as one of the youngest heads of department, also mentioned I was a marathoner. The client, a stately gent with a khate peete ghar wala paunch assessed me from my coiffed hair to my heels for a full minute and declared, “She doesn’t look like a runner”. He probably was indicating I was fat, but last I checked, that was never something that stopped anyone from running. But ouch, that stung and stayed with me all these years.

Women’s bodies are subjected to intense scrutiny and women living with medical conditions obviously have to deal with this as well. One in five women in India live with another form of invisible illness, PCOS (Poly-Cystic Ovarian Syndrome), which more often than not leads to insulin resistance and diabetes. If you have PCOS, you’ve most definitely dealt with hurtful comments like, “You’ve put on so much weight”, or “Oh God, are you a lady with a mustache, haha?”, or “When are you planning a baby?”, none of which should be anyone’s concern, but in the Indian society and culture, it is.

With the advent of technology, wearable diabetes assistive medical tech is a reality but also a burden for women. This is also what makes our ‘invisible illness’ more visible and invites questioning looks and unwarranted comments. I wear a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) device on the back of my arm and a pager-like insulin pump on my tummy or back. Very often, I am happy to educate curious strangers on what these devices are and the different types of diabetes because at this point I’m pretty comfortable with my body and its bionic bits.

Often, young women or teenaged girls with diabetes hide or remove this life saving technology (which is in itself a privilege to own, but more on that later) to avoid sharp or petty comments. Many women also live with dangerous eating disorders like diabulimia (diabetes + bulimia) which is when people with type 1 diabetes deliberately give themselves less insulin (and therefore run their blood sugars dangerously high) in order to be thin and fit in with crushing social constructs of beauty.

For an Indian woman with an ‘invisible illness’ marriage is a minefield, compromise or a necessity – none of which sound appealing to volunteer for. In the Indian arranged marriage market scenario, if you’re a woman of marriageable age and diabetic (not even considering skin colour, weight, potential procreation skills, sanskaar, finances or caste/class, horoscopes, those weigh in heavily for everyone), you’re considered ‘doomed’. I’ve seen bright, intelligent, attractive women with an invisible illness such as diabetes lose their sense of balance as they get pulled into the charade. Highly qualified, razor sharp professionals are advised “Beta, you’ll have to compromise little na, you have diabetes and hum ladki waale hai”. The same modern, urbane parents that are squeamish with their daughters dating are now pulling prospective grooms only from the ‘disabled/viklang’ section of matrimonial sites because “Bete let’s be realistic, who else will agree to the rishta, right?”

Many years ago, I received a phone call from an older ‘well-wisher’ asking if I was vegetarian or non-vegetarian? (non-vegetarian, in case this deep question about a random, ranting woman troubles you too.) Silly me, I thought they were organising a feast and inviting me over but I was wrong. “See there’s a very nice Gujarati boy who’s looking for a homely, vegetarian girl, so I thought you..” Wait, right there! Stop thinking! I don’t remember signing up for your free matrimonial services, thank you very much. Often parents decide to not disclose their child’s medical condition for fear of rejection. In a patriarchal society, even when women with an invisible illness such as diabetes do marry, problems do not necessarily end. If anything, they actually begin.

Often parents decide to not disclose their child’s medical condition for fear of rejection in the wedding industry. In a patriarchal society, even when women with an invisible illness such as diabetes do marry, problems do not necessarily end. If anything, they actually begin.

Firstly, the woman is made to believe by repeated reminders that someone did her and her family a favour by agreeing to marry her less-than-perfect-pancreas self. Then there would be pressure to perform, of course. Marriage, babies, the unpaid labour of mostly singularly managing household duties, social obligations and other niceties (all of this with double the spotlight, like you’re a trapeze artist in a circus, except you’re not). Add to this if the woman is financially dependent, god save her (more likely a degree or job might save her but you know how some ‘respectable’ families might not like that), because then her life depends on the ration of insulin or other medication that may or may not be provided to her.

Also read: Living With Fibromyalgia: An Invisible And Chronic Illness

All of this and more messes with our minds. It is no surprise then, that women with diabetes struggle a lot more with mental health issues and societal pressures than several other demographics. The Buddy Project is a mobile app based helpline led by multilingual and trained volunteers with lived experience of diabetes offering psychosocial and diabetes support.

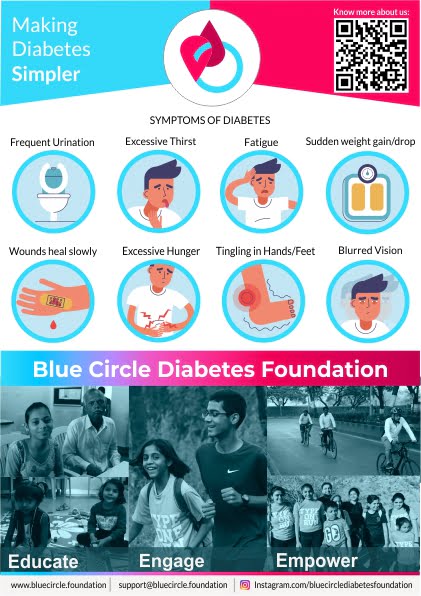

Nupur Lalvani runs Blue Circle Diabetes Foundation, an NGO and community for diabetes awareness and advocacy in India. When not talking diabetes, she’s either running, writing or gardening. She can be found on Twitter, Instagram & Facebook.

Beautifully articulated Nupur. You are a True Inspiration. More Power to you! Respect!