In this series, Women In Power, we feature women who have done groundbreaking work in the field of gender, sexuality, women’s rights and the likes to get an insight into their lives and their work. More and more people are joining the feminist movement and working on gender and we wish to bring them in the limelight, one life at a time.

More often than not, we end up dissociating ourselves from the reality of the world, consciously or unconsciously. Consequently, we start living lives with selected struggles and battles, leaving out a lot of them at the same time. Female Genital Mutilation is one such reality that a lot of us still refuse to acknowledge and speak about, eventually adding to the misery of a lot of women and girls. I try to uncover this secret through the interview of an organisation working for this issue, called ‘Sahiyo’ and start a more active dialogue around it.

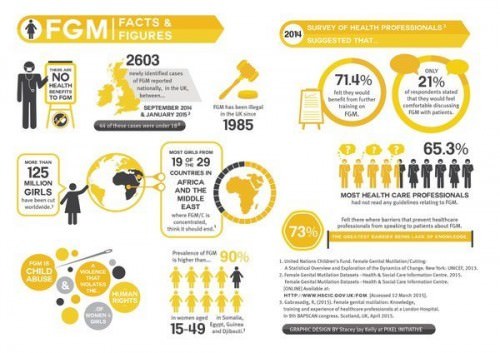

Female Genital Mutilation(FGM) is one of the practices that is carried out across the globe, even today. Every culture justifies it and legitimizes it, despite the declaration by the World Health Organisation, UNICEF and UNFPA, that it is a “violation of the human rights of girls and women.” It states that more than 200 million girls and women alive today have been cut in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia where FGM is concentrated.

Female Genital Mutilation infographic by Pixel Initiative

Sahiyo (the word ‘sahiyo‘ is a Bohra Gujarati word for ‘saheliyon’/’friends’) is a group of five powerful women, who work in dynamic fields and have come together with the primary aim of bringing an end to the practice of female circumcision/ khatna/ sunnah. It is dedicated to empower Dawoodi Bohra and other Asian communities to end Female Genital Cutting (FGC) and create positive social change. It aims to bring to fore the values of consent, a child’s/woman’s rights over her own body and normalize female sexuality.

I interviewed the Sahiyo team, comprising of Mariya Taher, Aarefa Johari, Shaheeda Tavawalla-Kirtane, Priya Goswami and Insia Dariwala about their work and about the practice of FGM in general, below are their responses along with the questions.

How do you think FGM, Female Genital Circumcision and Female Genital Cutting are different? Why does Sahiyo prefer to use the last one? What, in this sense, is the significance of the term ‘khatna’?

Officially, WHO has termed all forms of female genital cutting as ‘mutilation’, and the term FGM has grown familiar among activists and communities around the world. However, we understand that some communities practicing this ritual might not necessarily believe they are mutilating or harming their girls. We avoid the label ‘mutilation’ and use the more neutral term “female genital cutting” (FGC), instead. Khatna is the generic term used by the Dawoodi Bohra community to refer to Type 1 FGC. There is a strong sentiment in the community that the form of ‘female circumcision’ practiced in the Dawoodi Bohra community is in no way related to ‘FGM’ as recognised by WHO or as practiced in many African countries.

What are the major functions of Sahiyo? Along with its presence on the internet, are there also some parallel measures taken or planned outside it?

Aarefa Johari as a part of Sahiyo’s “I Am A Bohra” Photo Campaign

At this moment, we are mainly focused on creating a dialogue on the practice of khatna amongst both genders through the medium of storytelling, as well as spreading awareness on the subject. Since it has been a firmly guarded ‘secret’ by everyone in the community, we would like more men and women to talk about their experiences and share their personal views on khatna, thereby encouraging others to come out and do the same.

Besides our outreach through the internet, we are already disseminating information on khatna through various media channels, including newspapers, magazines and television, as well as drawing attention to this practice amongst the Dawoodi Bohra community by attending conferences and seminars.

We have also undergone a global online survey to understand the extent of the practice. Over four hundred women have taken the survey from around the world. We are currently analyzing the results of the survey and hope to release a report by May.

Could you throw some light on the khatna tradition of the Dawoodi Bohra community? What are the most common reasons given by it to carry out and sustain the practice?

Khatna is typically performed when a girl is between 6 to 9 years of age, and is a practice carried down from mother to daughter, with usually no involvement from the male members of the family. The ritual was traditionally carried out by traditional cutter, but mothers and grandmothers now also take girls to hospitals or private clinics, particularly in the bigger cities.

Dawoodi Bohras claim to practice Type I FGM/FGC. In the majority of cases only a part of the prepuce or the clitoral hood is removed, but we have heard; particularly when the khatna is performed by a traditional cutter who has little or no knowledge of anatomy and/or formal education, women have reported that either they had a part of the clitoris or all of the clitoris cut. The extent and degree of cutting, of course, may vary significantly, depending on the environment and the state of mind, anxiety levels, preparedness, etc. of the child.

Conversations with women from the community have thrown light on the various reasons cited for performing FGC amongst the Dawoodi Bohra and these include the following:

- To maintain physical hygiene and cleanliness (termed as a ‘taharat‘),

- Like male circumcision, it represents the attainment of status as a Muslim,

- It is a long-standing Dawoodi Bohra custom/tradition that must be followed,

- To prevent diseases like uterine cancer, urinary tract infections,

- It is a religious dictate and faith-based responsibility that is sunnah,

- To discourage promiscuity by reducing sexual libido and suppressing illicit sexual urges (i.e. to curb ‘hawas‘), and thus ensuring fidelity in a marriage,

- that an uncircumcised woman is considered ‘haram‘ i.e. forbidden to Dawoodi Bohra men,

- Because of the above reason, it is considered a societal requirement for increasing the chances of finding an eligible Dawoodi Bohra husband, and

- To enhance a woman’s sexual pleasure and enjoyment within the context of marriage.

What do you think could be the reasons for khatna to be carried out on girls in the initial years of their life?

Well, to quote an article by Rehanna Ghadially called “All for ‘Izzat’: The Practice of Female Circumcision among Bohra Muslims in India” Manushi – A Journal about Women and Society No.66. pg. 17-20, 1991:

“The choice of the particular age is not clear. The girl is considered nadaan (innocent) and nasamaj (not capable of understanding). She is considered not capable of understanding what is being done to her and at the same time she is considered sufficiently mature to continue the tradition when she has her own daughter.”

Do you think such communities are aware of the medical consequences of FGM?

Most women are aware of the practice of FGC, as practiced in Africa, and condemn it strongly. They know the various dangers associated with such an act of extreme cruelty. However, since the community does not view khatna in the same light, they are not aware of the long-term consequences of the emotional and psychological damage associated with it. Also, as most Type 1 (where a piece of the clitoral hood is removed) procedures leave no scarring or physical damage, most are not aware of the extreme short-term consequences, unless a procedure is botched and there is excessive bleeding.

The World Health Organisation classifies the practice of FGM into 4 types. Which ones do you think are the most common in Asia and why?

Source: Wikipedia

The existence of FGC in Asia has only been acknowledged in the past few years. There is very little research out there regarding what forms are practiced, however, of the research that does exist, it is believed that Type 1 & 2 are practiced in Asia.

From our own observations, we can most certainly comment on the Type of FGC practiced in the Dawoodi Bohra community, and as mentioned earlier, it is defined as Type 1. In our dialogue with women from other communities in South Asia who also practice FGC, we have learnt that all of them practice something along the lines of the least invasive Types 1 and 4. We cannot offer an explanation for why Type 1 and 4 are practiced in Asia, but a wild guess could be because of the influence of Islam, which allows women a high standing in society. As FGM is claimed to be essentially an African ‘tribal’ practice aimed to oppress women, the above could be possible and thus it is difficult to give a reasoning for why communities in Asia chose to embrace the least severe forms during the movement of this practice from Africa to Asia via the Middle East (Yemen, for Dawoodi Bohras).

How is female circumcision different from male circumcision? Is the consent usually absent in both the cases?

Some Dawoodi Bohras perceive the removal of the clitoral hood and the clitoris to be the female equivalent of cutting the male foreskin. Whether these two acts are comparable is a subject of intense debate among activists and medical professionals around the world. Among Dawoodi Bohras, both are performed at an age when children are not old enough to give consent for it; approx. age 6 to 9 for girls and infancy for boys.

The underlying ideology behind the two practices differs significantly. The Dawoodi Bohra religious leadership does not publicly explain why khatna is made mandatory for girls in the community. Most community members, however, believe that the ritual is meant to moderate a woman’s sexual urges and prevents her from having premarital or extramarital affairs.

Male circumcision does not influence a man’s sexual desire or decrease his ability to orgasm, as it does not affect the sexual organ (i.e. the penis). FGC, on the other hand, could damage the sexual organs, inhibit pleasure and potentially cause severe pain and complications for women’s sexual and reproductive health. The practice serves to oppress women, reinforcing the perpetuation of their marginalization and inferior status in society. Male circumcision on the other hand is not rooted in a blatantly discriminatory ideology.

Mariya Taher writes in her account of her khatna story along with stories of other women that It cannot simply be considered an act continued by ignorant people, the reasons given for its’ continuation have been rationalized and been given cultural or religious significance. How do you think such a rationalization of this practice can be countered?

Because communities have rationalized FGC to be a cultural or religious practice, in working to end it, we have to use a multi-prong approach involving community education, research, policy, legislation, and prevention and support programs. The first step would be the opening of dialogue around the topic of khatna, carried out in the Bohra community at a global level. Additionally, you have to also acknowledge the power or idea of ‘tradition’ in everyday life, and begin to speak about how some traditions are not good traditions. Khatna is a form of gender violence, and in discussions with the community, that re-frame has to be made.

It is generally the women who perform the practice on other women. Who does Sahiyo aim to target; the women who conduct the practice or the ones who fall prey to it? And why?

As both the traditional cutters and the women who are subjected to it are equally victims of the patriarchal ecosystem within the Dawoodi Bohra community that allows this practice to persist, we aim to target both. Both the cutters and the ‘prey’ (i.e. the mothers, grandmothers, aunts, wives, daughters) are inextricably caught in the web of tradition, religion and righteous justification that permits the practice of khatna. Therefore, we cannot afford to ignore any party, including the men, all of whom contribute, willingly or by virtue of ignorance, to the perpetuation of this tradition. We need to engage all of them in discourse and attitudinal change that is essential to ensure elimination of this practice. They all need to first understand and then build consensus to eliminate this barbaric and un-Islamic practice today.

Why do you think this practice is still absent from most discourses around assaults on women? How does Sahiyo aim to change this?

Clearly, the fact that this practice is a highly guarded secret by the household women, who do not even share any information on the practice with the men in the family, ensures that this practice stays within the closed confines of the Dawoodi Bohra community. As a taboo topic within the community, the knowledge of khatna is completely absent from social discourse in India, until the time that a few brave women from the community went to the media in recent years. This explains why FGC is absent from the larger discourse around assaults on women, as no one beyond the community is even aware of its existence in India. Sahiyo aims to change this by encouraging dialogue on khatna. We want to get more women and men to engage on the topic, question its basis in religion and discuss its need and place in today’s day and age.

Priya Goswami’s ‘A Pinch of Skin’ has earned worldwide attention for sensitising the audiences about khatna. How do you think different modes of communication like the cinema are responsible in bringing home the awareness about FGC in India? Do you think this contributes in reaching the target community (here, the Bohra community) in a more effective way?

A Pinch of Skin generated a fair bit of media interest as well as dialogue on the practice, adding to the momentum of the anti-khatna movement. Films become a great way to showcase all that is happening and depict the common struggle on a worldwide platform. Also, films are a great indicator, a social barometer if you will.

For instance, all the protagonists of ‘A Pinch of Skin’ (initiated in 2011), requested anonymity in varying degree, therefore no identities were revealed in the film. In a quick span of five years, now women have come out in the open, revealing their identities, putting their pictures out there and there have been films and videos with people revealing themselves to the camera. Films are a great way to record, showcase, understand the ever changing dynamics.

A Pinch of Skin Trailer from priya goswami on Vimeo.

FGC is a global practice. In this sense, what is the current focus of Sahiyo and what are its future plans of expansion, if any?

As for our future plans, we would love to collaborate with other like-minded organisations who work in the space of pro-bono counselling and education among young women in schools and colleges, specifically in Dawoodi Bohra populated areas, to spread awareness about the practice of khatna. We plan to engage with women and men in the community through workshops, focus group discussions and even different kinds of art projects, which can be very cathartic for women. We would also like to work with other women’s rights and child rights organisations who would be interested in hosting expert panel discussions and round table to talks on the issue. At Sahiyo, we are also trying to explore the opportunity to make films/documentaries to spread awareness on the subject, as well as document the worldwide dialogue on the subject of female genital cutting and juxtapose it against the conversations and struggles within our community on the matter of khatna.

You can see their work on their website here as well as their FaceBook page and Twitter page.

About the author(s)

I work (read, 'write') to stay afloat.