Women’s studies have provided new and improved perspectives on major themes – women’s issues, gender, sexuality, caste, to name a few – that have a significant impact and role to play in society. It has also long been a part of the larger feminist movement in India.

Many women’s studies scholars have argued that the founding point of women’s studies goes back to the 1974 report Towards Equality, published by the Committee on the Status of Women in India (CWSI). CWSI was appointed by the government in 1972 to make a report on the condition of women in India, which was also the time when the feminist movement in India was witnessing a powerful rise.

Neera Desai and Vibhuti Patel, in their article Critical Review of Women’s Studies Researchers: 1975-1988, argue that while some commissions like National Commission on Labour (1969), the Expert Committee on Unemployment Estimates (1971) and the Report on the Committee on Unemployment (1973) had undertaken researches generally highlighting the wage discrimination, general oppression of women, unemployment among women, the social scientists as well as policy makers were not acutely aware of the various issues of women and therefore, there was no urgency among them to act on these issues.

It was the Towards Equality report which specially emphasised women’s increasingly distressing conditions in the spheres of health, employment, societal status and political participation, bringing these issues to the forefront. The findings prompted the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) to fund research projects in universities, which was another major development in the trajectory of women’s studies programs. In 1974, a unit for research on women was set up in the SNDT Women’s University, Bombay, officially becoming a centre in 1985.

Pappu argues that the Women’s Studies Cell in SNDT University initiated the feminist intervention in academia and “domains where knowledge is self-reflexively produced.” Even though the term ‘feminism’ was not used, mostly because of its association with the movement in the West, leading to a simplistic and hostile identification with the West, the feminist ideology made itself visible in the Women’s Studies perspective. Contemporary scholars of women’s studies argued that it was this perspective that, in an unprecedented measure, moved away from the ‘male’ or ‘mainstream’ point of view on the studies on women, thereby reiterating Desai and Patel’s arguments.

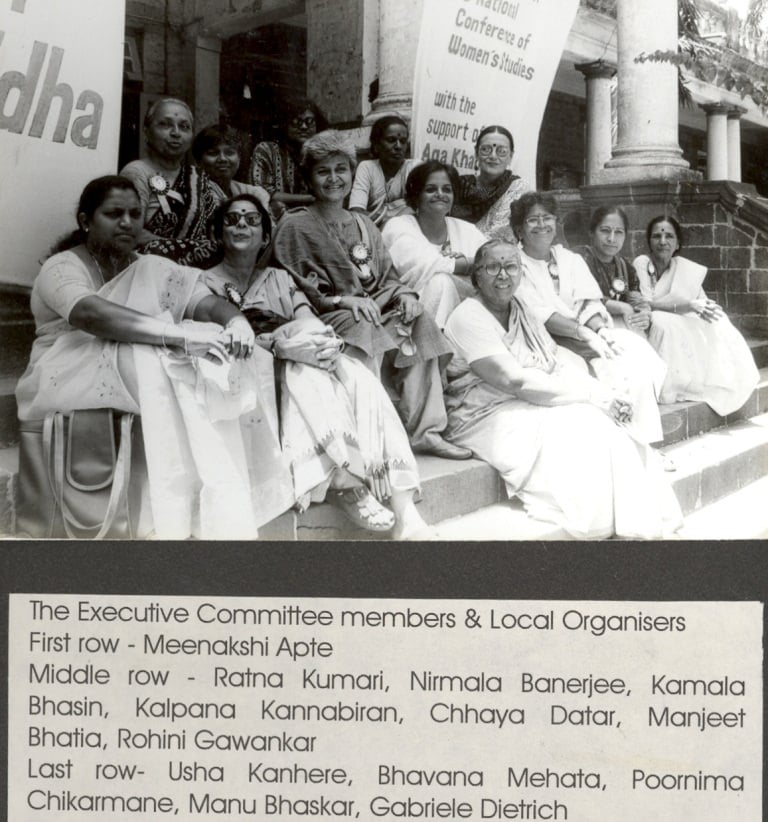

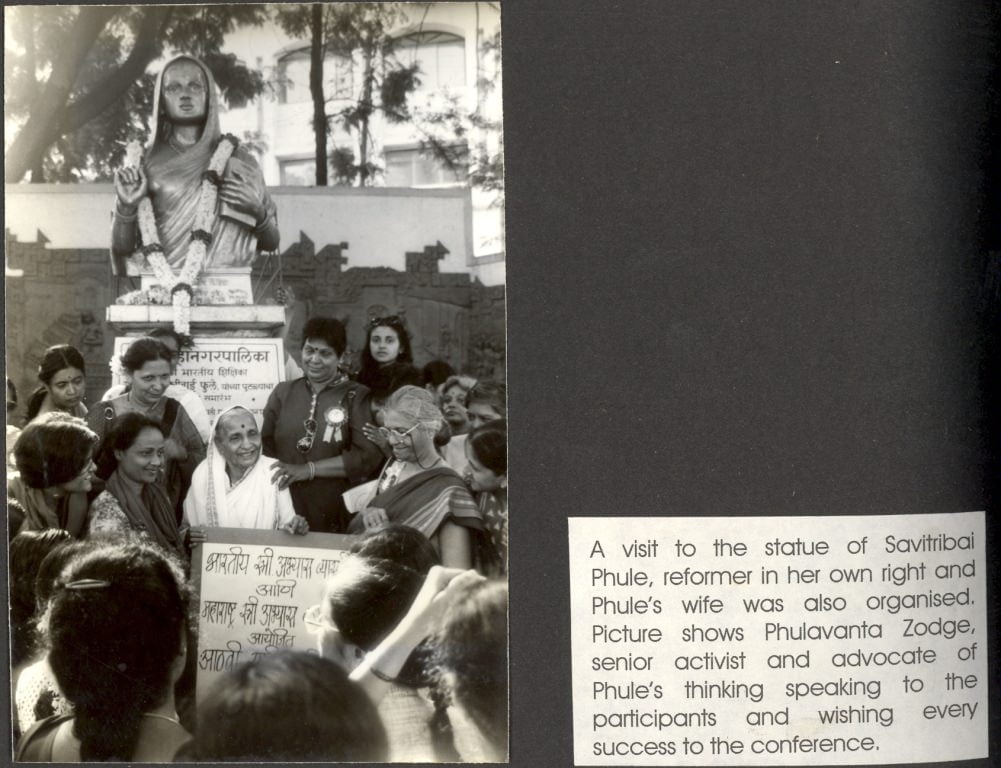

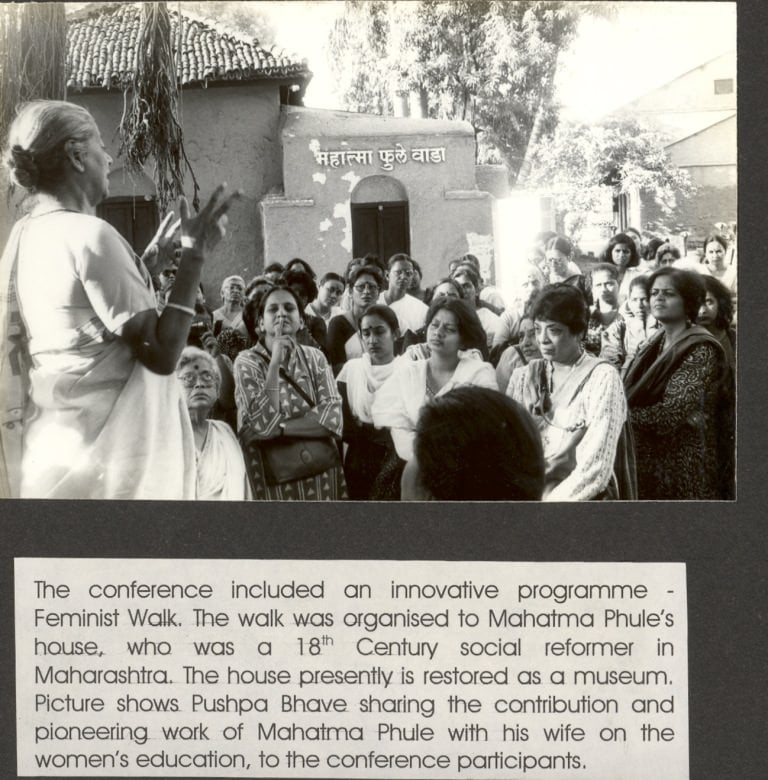

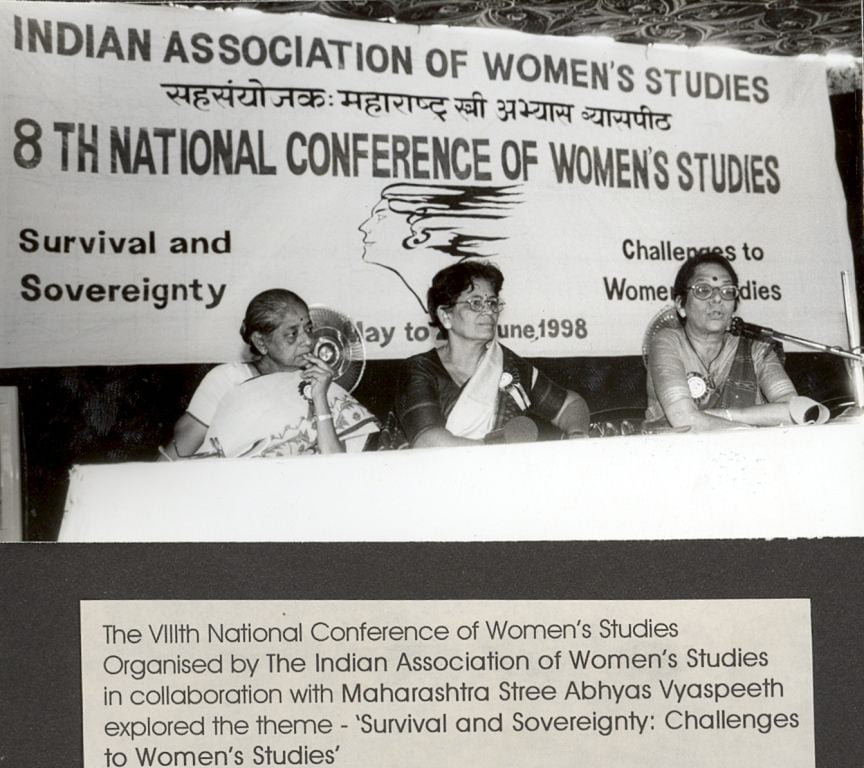

This process of institutionalization was facilitated by initiatives like the National Conference on Women’s Studies in 1981, where the idea of forming the Indian Association of Women’s Studies (IAWS) came into being. It became a platform for scholars and academics to share their work, journals, as well as the involvement of other institutions like publishing houses that help facilitate the growth of the field.

University Grants Commission (UGC) was also instrumental in institutionalizing women’s studies as an interdisciplinary discipline in higher education. For instance, UGC, along with IAWS, organized a seminar in 1985 on the importance of funding Women’s Studies Centres, which would be independent and on par with other departments and faculties. Emphasis was also laid on research and teaching. In 1986, UGC also brought out the guidelines for the Development of Women’s Studies in Indian Universities and Colleges. Extension activity, under which various development projects are undertaken, was also added later.

Along with universities, non-academic spaces like autonomous research centres were also established in the 1980s, Institute of Social Studies Trust, Centre for Women’s Development Studies (CWDS), the Institute of Social Studies Trust in Delhi, the Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies in Hyderabad and Chetna in Ahmedabad being some of the earliest ones. There were in total 16 autonomous organizations with a focus on women and 26 women’s rights organizations promoting women’s studies.

The aim of these research centres, as the ICSSR Committee also stated in its objectives, was to include research to generate new data and analyses on various aspects relating to women, adding new knowledge and a ‘critical perspective’ to social science academia. In 1979, a meeting of a group of women’s studies scholars held for discussing the scope of women’s studies defined its objectives as “transformation of spheres of knowledge production” through research, for changing the perspectives of contribution of women in society as well as focus on women centric issues in the constantly transforming Indian society. Through these measures the centres of women’s studies were meant to encourage an overall transformation of the academic community to address issues that concerned women’s lives.

Thus, as Maithreyi Krishna Raj also claimed in the book Women’s Studies in India: Some Perspectives, women’s studies program was founded to be “an instrument for women’s development and also as a necessary input to deepen the knowledge base of various disciplines…. women’s studies has to be understood not merely in the context of research and teaching but also action.” She adds that rather than a course with a curriculum and teaching methods, the women’s studies program was thought to be incorporating women’s voices in academia, by doing research from a feminist perspective on women, recovering women from history, making social sciences conscious of women’s issues and their involvement in society.

These developments also highlight that the early conceptions of women’s studies programs were those of being a complementary tool of women’s social activism. Scholars had dual tasks of creating social awareness and engaging in activism, while also developing a multidisciplinary knowledge system capable of understanding, explaining and theorising the experiences of women in different locations and in changing times. Thus, the objectives of the women’s movement and women’s studies programs overlapped, making them interrelated. Moreover, the fact that it was accepted by higher studies institutions within a decade of its introduction also shows its overall impact.

However, such variegated activities and responsibilities also brought complexities. Due to the involvement of centres with universities and colleges, they could not get involved in campaigns that were overtly critical of the government; sometimes they failed to receive the support of their institutions, or had to suffer a ghettoisation rather than impacting other departments. The autonomous organisations, on the other hand often lacked funding, and also did not offer regular teaching programs.

Also read: TISS Women’s Studies Centre Faces Threat Of Closure: Another Space of Dissent Silenced?

From the late 1990s, the issue has shifted to the nature and objectives of a women’s studies centre, but is now more focused on the methodology and content of women’s studies programs.

Pappu cites Frinde Maher and Nancy Schneidewind, who maintain that while feminist education should comprise both feminist scholarship and pedagogy, in practice the feminist pedagogy has been grossly neglected. Pappu argues that the many conferences and meetings held to discuss the strategies and objectives of women’s studies in India do not raise the question of pedagogy, or the methodology of teaching a multidisciplinary program as women’s studies.

Regarding the curriculum, there is little clarity as to who it is being designed for. The aim of women’s studies, as a part of the feminist movement, was to tackle the marginalization of women, especially those belonging to the lower strata of society, by creating awareness among students through these programs. The strategy of data accumulation along with feminist arguments was to achieve this goal, and it has been fruitful to an extent in the presence of the many subsequent women’s activists and women’s studies scholars.

However, there is still no guarantee, as Pappu argues, that when faced with particular data or analyses, the students would adhere to feminist ideology or could articulate feminist arguments themselves. Also, there is the issue of whether data documentation on the condition of women and accounts of women’s movements or campaigns are enough to constitute women’s studies.

Another issue is the lack of presence of students belonging to the lower strata of society, whose marginalisation forms the core of women’s studies, with the students mostly belonging to upper-class/caste groups taking the course. Since women’s studies as a program is also deeply involved in activism and social movements, the composition of the students also raises the concern of how different topics are discussed, like discrimination, abuse, etc. and how they impact the students to work for these issues later in life.

Pappu relates her own experiences and claims that while a short introduction to the course is extremely impactful for the women, it is not enough to equip them with the ability to apply this knowledge in politics or academics, for which a long-term engagement with the course is needed.

While women’s studies programs struggle with devising effective pedagogic strategies, there has been an increase in studies on women, both by academics and NGOs, which have contributed to bringing women’s issues to the forefront. However, the greater involvement of NGOs has also brought negative consequences with it. Their studies often ignore the feminist principles and sometimes even work against them. What’s disturbing is that women’s studies centres in the academic sector, as well as the publishing houses, have also started mimicking it. Thus, while there is wider involvement, the content of the research and studies has deteriorated and become problematic.

Also read: Alagappa University’s Women’s Studies Department Teaches Home Science And Beauty Therapy

The way ahead for women’s studies programs is thus full of challenges. The program should not give in to the academic, bureaucratic and administrative constraints, while also guiding other institutions in research work by providing feminist and methodological tools of feminist critique. There should also be a constant revising and reviewing of the work so that new theories and strategies can be developed with time.

References:

- Anandhi S., and Padmini Swaminathan. “Making It Relevant: Mapping the Meaning of Women’s Studies in Tamil Nadu.” Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 42 (2006): 4444-454.

- Mazumdar, V. Emergence of women’s question and role of women’s studies. New Delhi: Centre for Women’s Development Studies, 1985.

- Pappu, Rekha. “Constituting a Field: Women’s Studies in Higher Education.” Indian Journal of Gender Studies Vol 9, Issue 2 (2002): 221 – 234

- Women’s Studies in India: An Overview. Bangalore: Higher Education Cell, 2008

- Salutes to Vina Mazumdar, doyenne of women’s studies, FeministsIndia.com

- Why Women’s Studies, Economic and Political Weekly

Featured Image Credit: IAWS.org

About the author(s)

Himanshi is pursuing Masters in History and hopes to be a historian one day. She loves to read books, and even more to collect them. In her free time, she likes to explore historical haunts. Also, she is a foodie and spaghetti makes her heart race.

It is well written considering the structure, but it has named neera desai as the author of a text she never wrote. It is Anuradha Mathu. please proofread before posting such articles.