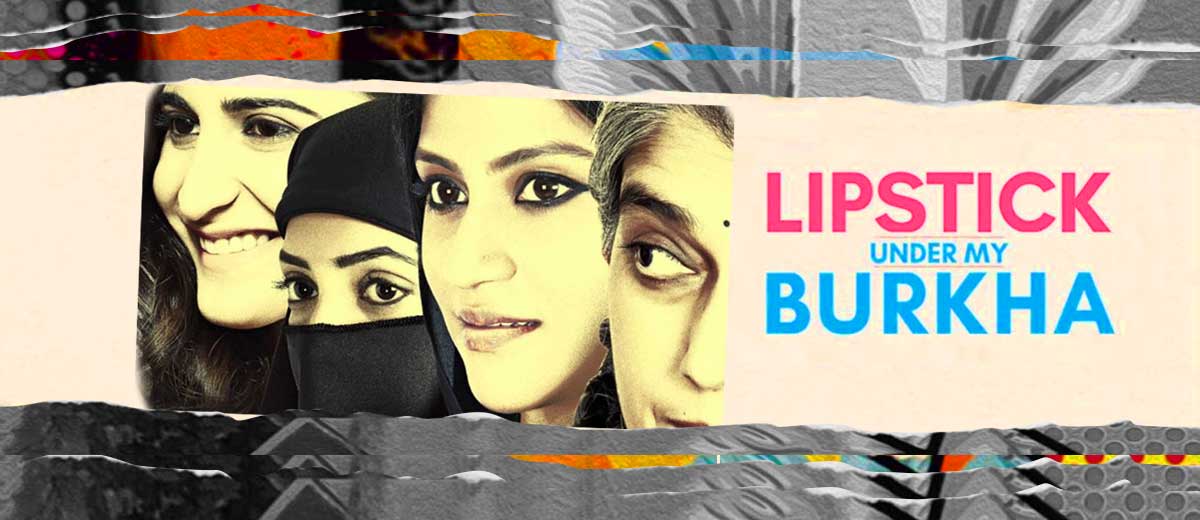

Before you read this article, I have a confession to make, I’m not really a Bollywood fan and a major reason is its lack of well-rounded women characters. But the winds of change have been a-coming, and this has provided us with much needed movies in recent years like Angry Indian Goddesses, Pink, Parched, Anaarkali of Aarah etc. As I walked into the seedy Gaiety Galaxy multiplex in Bandra, Mumbai to watch Lipstick under my Burkha, I was delighted to see that it was mainly occupied by women of all ages. Hear that, film-makers? Gone are the days when your audience was largely male. If you make ‘lady-oriented’ films for us we’ll come flocking in hordes.

In the 130 minutes that followed, Lipstick showed me things that I, a rare viewer of Hindi films, have never seen before in Indian cinema. The erotic yearnings of a woman well past her sexual i.e. child-rearing prime. The simple yet forbidden aspirations of a college going young girl. The dilemma of a young woman having to choose between familial security and true love/lust. And the turbulent private life of a woman married to a sexist brute.

Hear that, film-makers? If you make ‘lady-oriented’ films for us we’ll come flocking in hordes.

Above all, the movie’s portrayal of female sexual desire – a subject so inflammatory that the film almost didn’t pass the censors – was carried out with candour and empathy. (Sure, in the case of Buaji’s character it was done in a way that incited laughter, but we weren’t laughing at her desire so much so as her own astonishment at its presence.) To be honest, I felt that the handling of sex and sexuality was quite sanitised, as the movie is more about sexual desire rather than explicit sex; more sensual than bawdy. (Oh wait, that might be because of the numerous cuts made by the censor board…) It’s perplexing to think of how films like Kya Kool Hain Hum can make the cut but show the raw desire of women and suddenly it’s too much for our precious sanskaars.

Also Read: The Hypocrisy Of Censorship: Lipstick Under My Burkha Vs Films By CBFC’s Nihalani

This is especially because each of the stories of the four characters, represents a particular period of womanhood – youth, bachelorette life, married life and widowhood – encompassing a set of very probable experiences that can or do happen to women today. Be it Rehana’s escapades of deceiving her controlling parents for a conventional breath of freedom which involves shoplifting clothes and partying, or Leela’s not-so-furtive love affair and her aversion toward the confines of married domesticity headed her way. Each narrative had a relatable hook for someone seated in the audience. For instance, I held my breath as Rehana gave the slip to her parents and giggled as she changed clothes after leaving her house as I have been in very similar territory before. And Leela’s experience brought to mind how rants about parents bringing up the topic of shaadi is becoming increasingly common amongst my women friends.

As for Shirin’s story, in a society where contraception remains the onus of women and marital rape is not criminalised, we can only guess at the number of women in our lives who are nightly violated by their societally approved spouses, and for whom using contraception is an act of rebellion. Lastly, Usha’s pursuit of her sexual fantasies and the resultant consequences it brings, doesn’t only point out to how older women are desexualised by society but how even the most innocuous expression of sexual desire by women is perceived by many (read censor board too) as unnatural and vile.

Despite their trouble-filled double lives, the women in Lipstick are not mere victims of the patriarchal order. Their courage and resilience to continue dreaming in a world that won’t allow any of it, shines through the plot, like the vibrant red of their lipsticks and nail paints that gleam through the respectable dullness of their clothes. (Except Leela’s of course.)

Despite their trouble-filled double lives, the women in Lipstick are not mere victims of the patriarchal order.

The last scene is an anti-climax, where the double lives of the protagonists have been exposed. They have been hurt, ridiculed and shown their place by their ‘loved’ ones and the future doesn’t look too bright. And yet, the four protagonists manage to share a laugh at the book Lipstick Walein Sapne which tells the sensual exploits of a character called Rosie, excerpts of which have been the symbolic voice-over for our heroines’ bold and clandestine experiences at fitting intervals throughout the movie.

As the younger women woefully say that such books put fantasies in their head, Usha declares that they instead encourage one to dream. It’s not an optimistic end, and that makes it all the grander, the finale’s message is a typically filmic one that points out why we watch movies in the first place – because they dare us to dream, to imagine other lives. And so in this vein Lipstick Under My Burkha is an excellent place for a new start.

Featured Image Credit: Newslaundry

About the author(s)

Nolina Minj is a freelance writer and researcher. She is a gender and decolonial studies enthusiast, book hoarder and Hispanophile.