A picture pops up on your Facebook feed that makes you pause. It’s a close-up of someone’s desk, where the pens are arranged neatly and the laptop and books are aligned perfectly. The caption says “Ah, just feeling a little OCD today.” The comments range from “Wow that looks so cool – wish I could have some of that OCD, lol” and “Damn, you’re crazy.” There is one hidden, overlooked comment from someone saying “That’s not even what OCD is,” and you feel camaraderie towards this lone fighter.

You look around your room, with its hundreds of dizzying stimuli you want to fix, the pain in your temples throbbing from the thoughts that won’t shut up for even five seconds, down to your peeling and cracked palms that have dried out from the fifth wash in the last two hours alone. Hardly a picture that would get likes and comments. You know the words that people have used against you when they got a real taste of what it’s like: “psycho” (even though you’re not suffering from psychosis), “stuck-up” (even though you wish you could relax), “bossy b*tch” (even though you would never try to make someone else fill your brain’s compulsive demands), “monster” (even though the real monster is your brain, which you’re trying to fight everyday).

The National Institute of Mental Health defines OCD (Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder) as: “a common, chronic and long-lasting disorder in which a person has uncontrollable, recurring thoughts (obsessions) and behaviours (compulsions) that he or she feels the urge to repeat over and over.”

Defining the experience of living with it is a lot harder, though. Unlike our need for everything to be just perfect, trying to explain it is not as perfect a process as we would like for it to be. Trying to navigate life when you have OCD is not something you can look up in a user manual – for one, everyone who suffers from it has a different response to it and a different source of their anxiety. OCD isn’t necessarily always washing your hands or needing a certain number of things because of superstitions. An OCD-sufferer who washes their hands a lot may do so because their brain tells them they’re unclean and can lead to disease. Another OCD-sufferer might have no such thoughts nor feel the need to be clean at all.

OCD isn’t necessarily always washing your hands or needing a certain number of things because of superstitions.

Try putting three OCD-sufferers in the same room and it’s most likely to end up in a disaster because no two people’s experiences are the same. Some people have a more O-centric OCD (leaning more towards repetitive thoughts and obsessions), some have a more C-centric one (leaning towards acting on compulsive urges), and some have both.

Person A with OCD could walk into a room with an empty bookshelf and arrange all the books in alphabetical order in series title order, and Person B with OCD would likely lose their mind because their brain needs it to be organised by size. Person C with OCD might not even care about either of those things but might be hyper-fixated on getting rid of the shelf altogether because their brain believes it doesn’t belong in the room. Take a look at Cadabam’s’ outline of the basic categories and types of OCD – chances are, some people fit into more than one category, too.

The organisational example is only a basic example of compulsive behaviour. I may spend a lot of time meticulously organising my things, and maybe I get itchy and uncomfortable for the whole day when I don’t have 3 eggs, 3 bread slices toasted to 3 minutes, with 3 slices of bacon, and perhaps, yes, I feel ill if I don’t wash my hands every hour.

But it’s more than that.

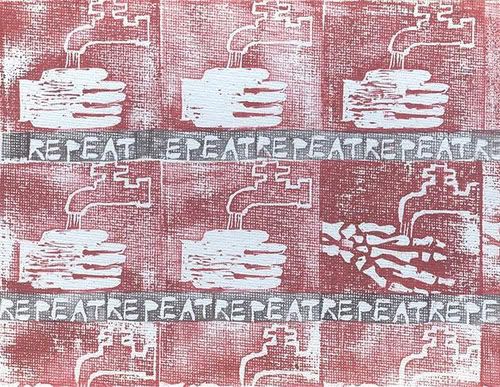

It’s the voice in my head constantly telling me that if I don’t do any of these things, then my entire life is going to come crumbling down. It’s the intense fear of needing to control everything around me – otherwise something bad will happen. It’s the fear that if I don’t double check the front door every two hours then someone in my house will most certainly die. It’s the record stuck in my head going “do it, do it, do it, do it, do it,” until I know the only way to stop it is to do what my brain wants me to do.

I’ve been told before that my OCD is a blessing. That people envy how organised I am, how well-planned everything I do is. My perfectionism, I’m told, is what any employer would want. They wish they could emulate me to bring some order into their lives.

I don’t know how to tell them that if I don’t plan everything I do, then I’ll have an anxiety attack. I don’t know how to tell that if I get woken up during a time slotted for sleep, then I’ll likely cry and scream for hours. I don’t know how to tell them that every time I submit a paper in school, I spend days panicking that I’ve put a full stop in the wrong place (even though I know I spent four hours on grammar check alone). I don’t know to tell them that perfectionism doesn’t only mean having an aesthetically pleasing planner with my work process carefully laid out – sometimes it means not moving an inch until I’m ready to give my absolute 100% and then spending the days before a deadline sleepless, bleary eyed, shaking and crying because I need to get it right.

All this while still fitting a stereotypical idea of what OCD symptoms look like. What about OCD-sufferers who live a visibly disorganised, messy life because their compulsive thoughts have nothing to do with their work ethic or what their environment looks like? What about OCD-sufferers whose brains are more focused on perfecting their physical selves (eating disorders are sometimes linked to OCD), or OCD-sufferers whose entire lives waste away because they fixate on their compulsive needs (addictions have also been linked to OCD), or OCD-sufferers who don’t care about being obsessed with safety because they’re more focused on acting on the compulsive need to be reckless?

I don’t know how to tell them that if I don’t plan everything I do, then I’ll have an anxiety attack.

There is nothing quirky or awesome about having a disorder that keeps you in a constant chokehold. It is double, triple, quadruple checking every move you make because you don’t trust your own eyes or mind. It is shaking from head to toe until you act on your thoughts because it’s the only way to release them. It’s picking at the things around you, with your skin, your hair, your nails because if you don’t give your body something to do, then you feel helpless.

The examples I’ve used so far are only the socially acceptable displays of OCD. Some of us have worse compulsive thoughts, because any voice in your head is a voice that can turn dangerous. Thoughts of hurting the people around us, thoughts that we consider “taboo”, thoughts of even hurting ourselves.

Sometimes OCD isn’t just about fixing that one pencil that isn’t placed how you want it to be. Sometimes it can be repetitive thoughts to break something even if you rationally don’t have any reason to – imagining it shatter to pieces, the sound it would make, the feel of the pieces in your hand, the words “break it, break it, break it, break it” revolving in your head while your conscious thoughts battle it, saying “No, why, I don’t need to?” (If you’re someone who is coping with compulsive thoughts, especially dangerous ones, then please reach out. There are professionals who want to help you defeat them).

Perhaps it is impossible to fully explain in a single post how it feels to live with your brain going 200 km/h every day – and that is when you’re not already battling other mental health problems. If OCD is bad enough on its own, it’s worse when coupled with depression, and mania, and panic disorders (sometimes one can be a symptom of the other, or both can be a symptom of another problem altogether). An already chaotic battle in your head quickly turns into an all-out war. Your OCD could be telling you to get up, get up, get up, get up, while your depression tells you to not bother moving again, while your anxiety spins wildly wondering how much time you’re wasting on fighting yourself.

There is nothing quirky or awesome about having a disorder that keeps you in a constant chokehold.

So, you can imagine how it feels to log onto your phone for a bit to try and relax your brain and see someone treating your mental illness as an organisational trick, or a Pinterest board. Or worse, clickbait posts like “21 Ways to Trigger Someone’s OCD” full of pictures and gifs that seem to cause amusement for others (these are usually the same people who will often “test” your OCD by rearranging your things and then laugh when you panic), but can actually trigger anxiety and fear for an OCD-sufferer. Somehow triggering someone’s OCD is considered a fun activity. Imagine reading an article like “5 Ways to Trigger Someone’s PTSD” or “10 Tricks Bound To Send Someone With Depression Off The Deep End” – does that show you the gravity of the situation?

OCD isn’t a feeling you have when you manage to plan out your month really well, or achieve symmetrical arrangement of your furniture. It isn’t being cleaner than average. It definitely isn’t micro-managing and bossing people around. It’s a constant mental battle that may manifest in some of these ways that barely skim the surface.

OCD being used as an adjective and a descriptor is not only spreading misinformation on the disorder itself, but also invalidating the experiences of people who actually suffer from it. Telling someone you have OCD doesn’t garner the level of compassion and patience when it’s thrown around so casually for extremely banal things. There is also a very odd understanding how OCD symptoms are received by people when they come from different genders.

Somehow triggering someone’s OCD is considered a fun activity.

Oftentimes, a lot of people will attribute my visible symptoms as something that comes with being a woman. The stereotype that women are better organised, more detail oriented, more “neat”, is something that derails any conversation I try to have about why I prefer things the way I do. This is a harmful generalisation.

One, the stereotype about women is skewed because despite it existing, women aren’t treated as good leaders. But it is also harmful because those are not traits that have anything to do with someone’s gender. Other genders who suffer from OCD face the same problems. If I’m having an anxiety attack over my schedule being thrown off, then I’m not just being “an emotional girl”. That is a sexist assumption, and also clubbing me under a category of “emotionally responsive” while disregarding the source of my discomfort.

Femininity being associated with hysteria and mental illness is a tactic that has been used for decades to invalidate women’s feelings, but to not only wrongly identify what qualifies as OCD and then dismiss at as a gendered disorder is offensive on multiple levels.

I have lost count of how many times I have gone on trips with my friends and they take one look at my overpacked bag and have a laugh. The conversation will start with mocking me for how much I choose to carry (without acknowledging that I pull my own weight and would never force someone else to suffer for my problem). Then it will turn to nitpicking on everything I’ve chosen to pack (despite most of them coming to me later to borrow things because I am better prepared). Then, it will turn to dismissal: “Arrey, she’s a girl. Of course, she’s going to go everywhere with her make up and skin care and hundreds of clothes.”

In that moment, the helplessness is indescribable. There is shame because the moment you say, “I feel anxious without these things,” you know you’re going to be mocked for being materialistic. There is a silent apology to all the girls in the room who are being stereotyped because of you. There is frustration and anger at yourself for needing more things than you can count (although you have counted them, over and over).

You want to shout: “No, no it’s not about looking good and keeping my skin healthy. I’m not carrying my 10-step-skin care routine because I want to be chic, I’m carrying it because if I don’t go through my 2-hour night time ritual then I will keep rocking back and forth in my sleep. I’m not carrying all these clothes because I want to be fashionable, but because I am terrified of feeling unprepared for any event. I’m not carrying all these bath products because I can’t function without my preferred brands, but because not following my shower-ritual to a tee will mean I will want to scratch my skin off for the whole day until I feel clean.”

But you can’t shout it because you’ll be labelled as hysterical. You can’t say it because your compulsive thoughts are already revving up in your head and sending your mental responses firing in different directions, and before you know it, the conversation has moved on and you’re left as a standing joke.

I am more than just my OCD, but it is also a huge part of my life, just like any mental illness is. Telling me to get over it because it’s “all in my head” (of course, it’s in my head, it’s a mental illness), telling me you’re envious of my horrendous experiences, assuming how my brain works just by observing the final step of an invisible 100-step-procedure, is unfair to me. It is unfair to everyone who suffers from it.

Also Read: Why You Need To Mind Your Language While Talking About Mental Illnesses

Instead of using it as an adjective, ask yourself why you think someone might have OCD and do some research. If someone tells you they have OCD, ask them how you can help them and if anything you do interferes with their rituals. This is one of the hardest steps I’ve found to do – not only because I know my OCD will interfere with someone else’s or their rituals and compulsive thoughts might be different from mine, but also because sometimes (because of how much misinformation exists about the disorder) many people either don’t know what OCD even is or confuse their symptoms for OCD when it might be something else.

That being said, the correct response to anyone admitting to having a mental illness (or suspecting that they do) is not to dismiss them or act skeptical, but to only show support and compassion, to show a willingness to help them from spiralling without being impatient and expecting more than they’re ready to give. No mental illness is easy to suffer from, even if someone comes across as an extremely put together and functional human being. To assume what someone’s symptoms might look like and attempt to validate/invalidate them is neither your job nor welcome.

Featured Image Source: Pinterest | Jessica

About the author(s)

Pallavi Varma grew up in Bangalore but spent a lot of her time living in the fantasy worlds she creates for her stories. She has a BA in English Honours from Christ University, an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University, along with being a professional binge-reader, kpop-enthusiast and Netflix-watcher.

Thank you for being so open about your OCD, which is such a misunderstood and misrepresented disorder. I’d also like to stress that it is also very treatable and you don’t have to suffer as you describe.My son had OCD so severe he could not even eat, and thankfully exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy, the first line psychological treatment for OCD, literally saved his life.Today he is a young man living life to the fullest. I recount my family’s story in my critically acclaimed book, Overcoming OCD: A Journey to Recovery (Rowman & Littlefield, January 2015) and discuss all aspects of the disorder on my blog at http://www.ocdtalk.wordpress.com. There truly is hope for all those who suffer from this insidious disorder!