Girliyapa’s Gully Bai, a spoof of the trailer for the movie Gully Boy, claims to do this: “Asli labour class se milaye Hindustan ko” (make India meet the real labour class). I hope that part of the video was sarcastic because the only thing they’ve helped India meet is the thriving upper caste ignorance and a non-existent aalsi labour class (lazy labour class).

Gully Bai’s central character is Manju, a domestic worker, who is portrayed as being incompetent, indolent and unchaste. She seems to always be late, uses Tinder and asks for more vegetables to be bought when she can’t even make rotis without burning them. Because of this, she is verbally and physically abused by her employers and the way she takes revenge is by being further incompetent, indolent and unchaste – but this time, taking pride in it.

The Reality of Indian Domestic Workers

In truth, the reality of India’s domestic workers is quite the polar opposite of what Gully Bai portrays it to be. Almost all of the close to 10 million domestic workers in India belong to marginalised communities – they are Adivasis, Dalits or landless OBCs. Most of them are migrant workers and a staggering number are women, several underaged. They are on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder.

They are made to work for long hours, given heavy workloads, subjected to verbal abuse, beatings and torture and have very few, if any, unions to seek recourse or solidarity from.

Domestic workers are part of the unorganised sector and have no laws safeguarding their exploitation or mistreatment. They are made to work for long hours, given heavy workloads, subjected to verbal abuse, beatings and torture and have very few, if any, unions to seek recourse or solidarity from. Let’s not forget the rampant sexual assault of domestic workers that goes deplorably unreported and unchecked due to the fact that their workplace is also the home of their bosses.

To add to all of this, domestic workers can be fired at the whims and fancies of their employers.

Could Manju bai survive in the real world?

Take all these facts into cognisance and watch the video again. Does a Manju bai really have the luxury of being lazy? Which Manju bai can actually say “Gaali de Marathi mein, mair aur do sunaegi” (if you insult me in Marathi, I’ll throw two right back at you) to her employer without the fear of losing her job the next moment, if not of getting assaulted? Which Manju bai would dare utter the words “Kaat lo pagaar, phir bhi late-ich aayegi” (cut my salary, I’m still going to come late for work), when oftentimes she can’t through the month with a salary cut?

A domestic worker refusing to fulfil the demands laid down by her employers, let alone make some of her own, would result in her losing her job. This directly affects her ability to pay for her basic needs. The employer, on the other hand, can easily find another person to do the job. Worst case scenario, they’ll have to clean their house themselves for a few days. The worst case scenario for Manju, however, would be having to starve for a few days.

But why even get to how her form of revolt is…inefficient, to say the least.

Is Manju bai actually lazy or do we like seeing her that way?

What makes this portrayal of domestic workers being lazy or a gossipmonger so easily digestible? Surely it’s been established that a group of people who are, by default, vulnerable, can’t afford to be slothful or spend enough time gossipping, by conventional standards, for them to earn this stereotype.

Also read: Domestic Workers In India Have No Laws Protecting Their Rights

Maybe it has something to do with the fact that we have different standards for people belonging to different classes. We don’t think poor people work hard enough. If they worked hard enough, they wouldn’t be poor, right? So we chastise them for the slightest slip-up. If your life depended on your job, you wouldn’t mess up, right? Their contribution to society is considered so inconsequential, that making even reasonable demands as part of it seems like asking for a lot. Why else would Manju asking for something as small as vegetables to cook food for her employers with, elicit a wild response?

The Underlying Casteism Of Gully Bai

We expect people like Manju to occupy such less space that even the idea of her sitting anywhere other than our floors feels like a personal affront. Simple Rajrah, in her article about Gully Bai, talks about the stereotypes of the “irritable kaamwali aunty, the expressionless chaukidaar who refuses to salute everyone, the crass, unskilled but arrogant autowala”. These stereotypes exist not because every person who does these jobs fits these descriptions; they exist because the slightest deviation from absolute submissiveness bothers us.

We are offended because we don’t consider ourselves their employers, we consider ourselves their saviours. We expect our domestic workers to be grateful to us for having provided them a job but we don’t seem to understand that it is a transaction – they provide us labour, we provide them money. The two parties owe each other nothing more. When our domestic workers ask for leave or refuse to do certain tasks, they are only exercising the labour rights the State should be legally providing them. They have no obligation to be subservient or grateful to us.

We don’t think poor people work hard enough. If they worked hard enough, they wouldn’t be poor, right?

There is inherent casteism in this dynamic. Domestic workers can rarely be seen sitting on the chairs or sofas in their employers’ houses. This is scarcely the case in the West. Where does this come from, if not Brahmanism? So when, in the video, Manju is shown as sitting on the couch and watching TV, while the lady of the house walks in carrying the laundry basket and Manju goes on to refuse to do the cleaning – it is almost surreal.

Is It Just A Bad Joke?

People could argue that that is the point of the video – it’s a joke, it’s a caricature of domestic workers. But nothing that elicits laughs at the expense of someone who neither consents to nor can afford to be the butt of it, should be considered a joke. As for caricatures, they can be for entertainment or be political. When a bunch of upper caste creators and actors get together to make a caricature out of a vulnerable, marginalised community – it is innately political. And the politics of this video harms the people who are already at the bottom. If it is caricatures you so vehemently want to make – make some of the people in, and with power. They can handle the damage. Marginalised people don’t deserve to.

I wish I could just call Gully Bai a 5-minute long bad joke and move on, but it isn’t as simple or harmless as that. Nothing said in this article is intended to imply that the creators deliberately want to perpetuate classism and casteism. I only intend to call for sensitivity when representing marginalised groups. Hire people from diverse backgrounds, hire people from lower castes, get their opinions on your ideas before making and releasing these videos. If you are profiting from the conditions of underprivileged people, the least you can do is ask them before doing so.

Also read: How Has The #MeToo Movement Affected The Lives Of Bengaluru Working Class Women?

What’s truly sad about Gully Bai is that the funniest aspect of it is not any of the ‘jokes’ the creators came up with. The funniest part is that the music accompanying this whole video that further helps cage domestic workers, is originally from Kanhaiya Kumar’s Azadi (Freedom) – a rallying call against “samantvaad, manuvaad, Brahmanvaad” (feaudalism, casteism, Brahmanism).

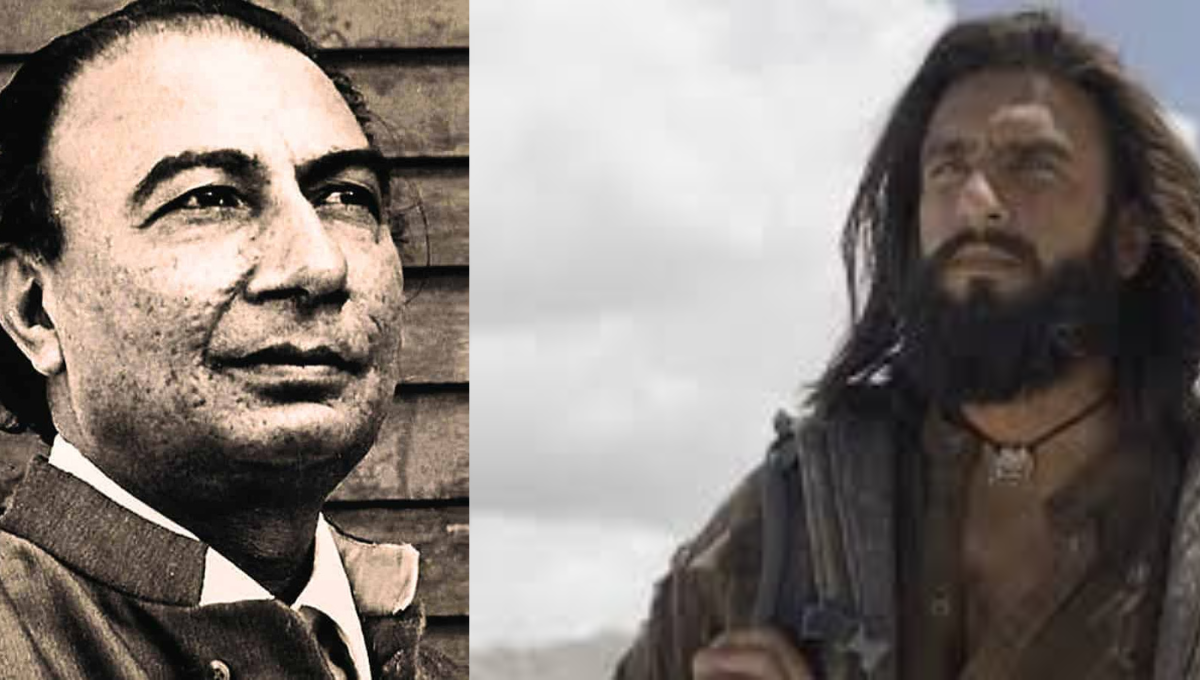

Featured Image Source: YouTube

About the author(s)

Hamsadhwani is a law student and anti-caste socialist feminist. Abolish the conditions that produce the prison.

Amazing article has been posted, we really impress, This article based on reality of every Indian women of labor background, they always look the way “apna bonus ayega”, aur kharcha chal jaega.

they are just away the sexual life, they didn’t enjoy sexual life even, always having tens, like “paise kaise ayega” now as we need to look beyond for them to fulfill there economical, physical and sexual needs.

Author raises several fair points. While Gullybai is deeply problematic in many ways, the author’s assumption that the domestic help can never afford to be incompetent, come late, not come at all etc indicates that either she was raised where there was continual supply of domestic labour or her own parents were good managers.

Most Indian comedy does target low hanging fruit in terms of cheap jokes. No wonder it becomes annoying to watch once you outgrow it.

It’s really impressive post. The way, Author has covered some valid points on labor class and casteism through movie concept, that’s awesome.