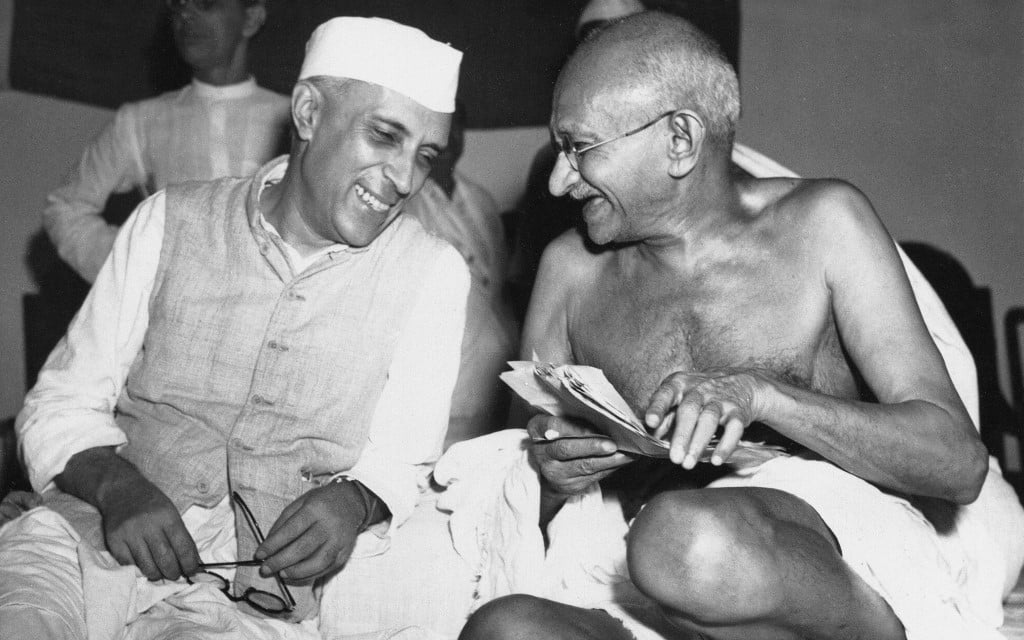

A noticeable trend in Indian politics, as early as at the time of independence, is the allocation of ‘nicknames’ to prominent political leaders. Names like ‘Pandit ji’, ‘Netaji’, ‘Mahatma’ or ‘Bapu’ have been reiterated in our history and civics textbooks through most of our middle school. “They were given these names out of love and adoration from their followers” is what my history teacher had said to me. Women politicians, however, had it slightly different. Their names ranged from ‘Gungi Gudia’, to ‘Amma’ to ‘Bitiya’. The question that then arises, is ‘why?’ Is there a politics to this nomenclature?

A little bit of research will reveal, yes there is. It is a very deliberate and calculated political strategy on part of politicians. All these titles are those with familial ties – it is an active attempt to de-sexualise themselves. It’s a peculiar phenomenon that is almost unique to Indian polity. This nicknaming isn’t specific to just women, but it is most often used by them. In the Indian traditional narrative, family hold tremendous value and positions of power and hierarchy within it are the important sources of authority.

Also read: How Jayalalithaa Combatted Sexism in Tamil Nadu Politics

When most of the electorate value such relationships, it is only logical for women to mould and manoeuvre themselves into the positions of ‘mother’, ‘elder sister’ or ‘aunt’. The nature of the State is paternalistic. This also means that leaders of the state on the social role of protector/provider. It ensures to their voters a sense of security and guarantee, that one would expect from a father or mother in their traditional roles.

Madhu Kishwar in an essay writes, “While Indian men have made it fairly difficult for ordinary women to feel comfortable as equal participants in the political domain, they tend to succumb easily to the demands of women who have the shrewdness and determination to grasp some dynastic or other leverage that provides them with the crucial opportunity to demonstrate that they are stronger and more resilient than the entire range of men in our politics…”

Further, Kishwar writes, “This is a variation of our family scene wherein many men

Women And Controlled Sexualities

Whenever it is about women, it is also about sex. Rumours around Jayalalitha and MGR, Mayawati and Kanshi Ram, Mamata Banerjee’s alleged secret marriage. For these women, entering politics and setting themselves aside from anything that could remotely be considered sexual, was one of the key reasons for their political successes. In the case of leaders like Mayawati, Mamata or Jayalalithaa, nomenclatures like Behenji, Didi or Amma “de-sexes” them and provides them with a mental and psychological shield in a male-dominated society with a patriarchal mindset.

“Perhaps the only way in which women’s sexuality can be accepted is if it is co-opted in a family structure, like if the leader is married or has a family.”

When they no longer possess reproductive powers, the need to control them, through their sexuality is not that important. Several articles online with titles such as, “Top 14 India’s Glamorous, Young & Cute Politicians” and “Six Indian Female Politicians that aged like fine wine” only further indicate the electorate’s obsession with women and sexuality, not sparing even those who aim to do serious work in the polity.

Male politicians are not bereft of sex scandals and rumours of illicit relationships. However, all the accusations made against them are aimed at their person, private lives, and manhood and it is almost never about their politics. This isn’t unique to India; the sexual lives and records of leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. were always held separate from their politics or political abilities.

According to Nishtha Gautam, an associate fellow (gender) at the Observer Research Foundation, “Perhaps the only way in which women’s sexuality can be accepted is if it is co-opted in a family structure, like if the leader is married or has a family.” Parties that build their reputation around a single cult leader tend to enforce this upon them, it is usually women who have to renounce their sexuality. De-sexualised leaders such as MK Karunanidhi or Mulayam Singh still have families to turn to, but Didi, Amma, and Behenji didn’t and do not.

Women Politicians And The Politics Of Image

Jayalalithaa inherited an empire from MGR that was based on his ‘larger-than-life’ superstar image. However, the way she projected herself was quite different; she disassociated herself from the extravagant visuals and imagery associated with MGR and her past in Cinema. For these women, it is not sufficient to de-sexualise themselves in a manner that is only in their authoritative relationship with state subjects, but also how they present themselves visually.

Clothes, apparently, make the woman. They must look asexual if not downright masculine. Mayawati for instance, with her short hair and plain salwar suits, Mamata Banerjee in her plain white saris and chappals, Jayalalithaa in plain pattern-less solid colours, none of them with make-up. Time and again, press and the electorate keep shifting focus from their politics to their appearances. Shobhaa De spends an entire day talking to Mamata Banerjee to come to the conclusion that she has an excellent hair dye. Hindustan Times did an entire piece on women politicians’ missing handbags. When, in the recent past, have male politicians been subject to such scrutiny at the cost of discussing their political agendas?

The Goddess Infatuation

The cult of the Goddess is a peculiarity of India, another facet of this ‘de-sexualised’ image. Even the most vocal pro-Hindutva male politicians wouldn’t be accorded the title of a male God. There could be male politicians on chariots or even demanding a Ram Mandir, but none of them would be considered anything close being associated with Shiva or Vishnu.

Women politicians are most often looked at as manifestation or incarnations of female Goddesses such as Shakti, Kali, or Durga. These ladies turn into ‘avenging deities’, Jayalalithaa avenging being pulled away from MGR’s funeral cortege. Mamata Banerjee avenging the CPM’s relentless attacks on her. Mayawati avenging the grave injustices and cruelty infringed upon the Dalit community through history. Vengeful women have an aura that is different from their male counterparts who might have the same ‘vengeful’ agendas. They turn into Kalis running amuck with garlands of the bloody heads of political foes and impudent bureaucrats who dared to cross them.

Desexualising politicians has always been an integral element of electoral politics in India. However, the brunt of this ‘requirement’ is borne by women politicians the most, as they find themselves in the center of a masculine and paternalistic state structure that makes no room for the feminine sexuality. In fact, a recent exception to this ‘desexualising’ necessity is Prime Minister Modi himself with his ‘Chhappan inch ki chaati’ (56-inch chest) which is intended to signify the stereotypically, alpha, muscular, macho, powerful, strong, metaphoric superman; whose very name makes enemies shiver in their boots. It is a symbol of prime sexuality, which when expressed by males only ooze prowess.

References

1. Jayalalithaa as Amma: Politicians’ Need to Tone Down Sexuality

2. Female Tetravalent of Indian Politics: Amma, Didi, Behenji, and now Baji

3. Behenji, Amma, Didi, Aunty: India’s 4 women CMs

4. Bapu, Behenji, Chacha, Amma: There’s politics behind naming

5. Decoding Didi, Amma, Behenji: Just Goddesses with mood swings?

6. Amma, Didi, Behenji: India’s female kingmakers

7. Saris and perfumes: How India’s male politicians see their female counterparts in Parliament

8. Six Indian Female Politicians Who Aged Like A Fine Wine

9. Top 14 India’s Glamorous, Young & Cute Politicians | Beauty With Brain

10. The cult of 56-Inches and toxic masculinity

11. The Case of the Missing Handbag

About the author(s)

Nayonika Sen is a Marxist feminist law student. Passionate about history, literature, writing, and smashing Patriarchies! Academic at heart.