Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.

Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.One of the key ways in which rape culture operates is the minimising of the trauma that gender-based violence. We see it everyday in the casual rape jokes made by our peers, by telling women that “boys will be boys” and that they should move on, by interrogating women on the ways they choose to respond to sexual violence – “why did you stay quiet then?”. Rape culture, and patriarchy, thrives on the assumption that rape, or gender-based violence ‘is not that big a deal’. This minimisation of the trauma of sexual violence leads to its normalisation. This is why we see so many acts of gender-based violence justified, explained away, or swept under the rug.

Now, how does the media perpetuate this problem?

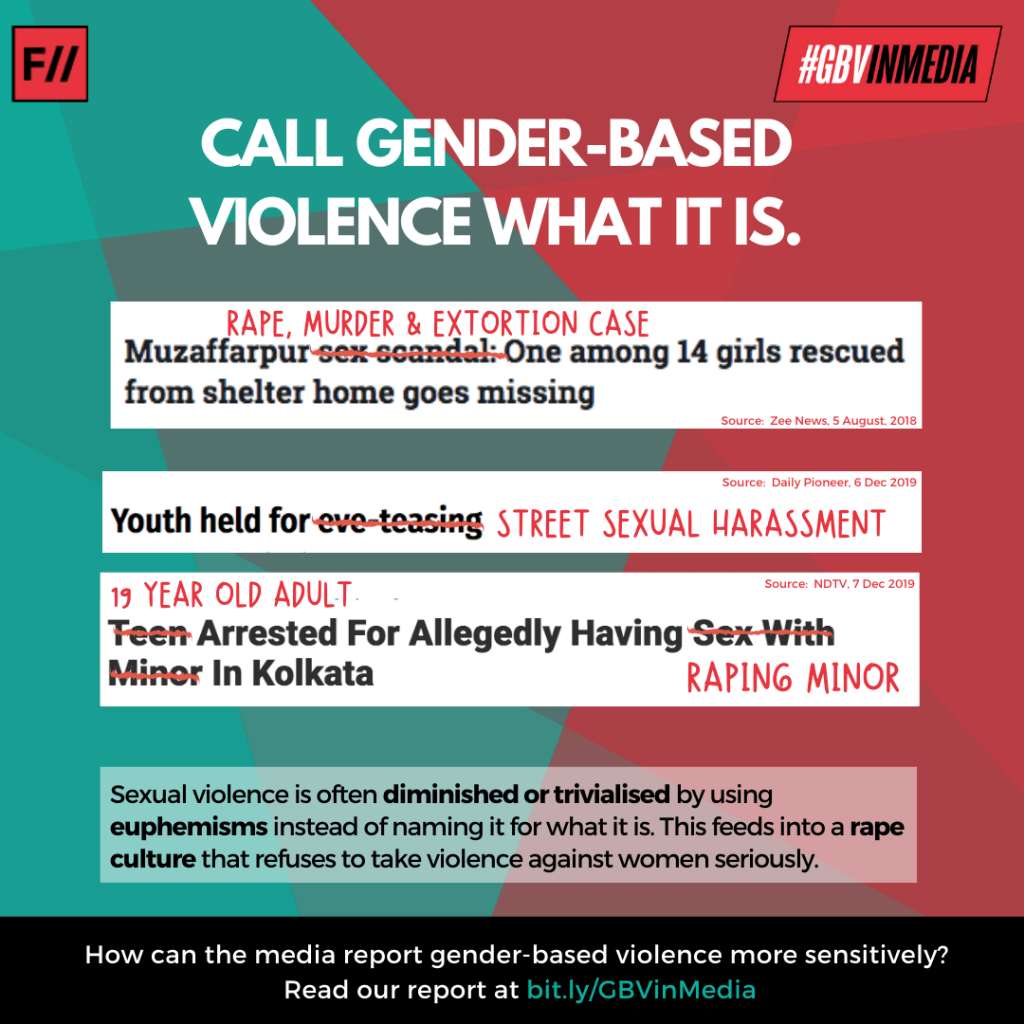

The media often refuses to term gender-based violence what it is. By using allusions and euphemisms rather than its correct terminology, it runs the risk of reducing the gravity of the crime, and negating survivors’ experiences of the trauma of sexual violence.

It is gender-based violence, not a ‘sex scandal’.

Rape is non-consensual and forceful sexual intercourse. Terms such as ‘sex scandal’ being used to describe rape sensationalises the incident, creating a provocative or titillating spectacle while minimising the gravity of the situation. It also casts aspersions on the survivor, leading to victim-blaming.

If the violence falls under the legal definition of the word ‘rape’, the media must not shy away from the term or use alternative terms such as ‘forced/coerced sex’ or ‘non-consensual sexual intercourse’. Gender experts have widely called rape an act of exerting dominance and power via sex. Highlighting the ‘sex’ instead of ‘dominance’ runs the risk of diminishing the crime of rape.

The Muzaffarpur shelter home case referred to above had multiple accounts of rape, sexual abuse and torture on at least 34 women and underage girls living in a state-run shelter home. By referring to it as a “sex scandal”, not only does it reduce the seriousness of the issue, but the word ‘scandal’ also implies that both parties (perpetrators and survivors) were equally at fault, or that both participated willingly.

Also read: Why Are Sensationalist Headlines Of GBV Cases A Problem?

It is sexual harassment, not ‘eve-teasing’.

Eve-teasing is a South Asian term broadly used to refer to cases of street sexual harassment and molestation. The use of the word ‘teasing’ minimizes the gravity and trauma of sexual violence, and engenders the belief that women ought to ignore it and not speak out about it.

He is a sexual harasser, not a ‘roadside Romeo’.

Similarly, the use of the term ‘roadside Romeo’ to describe sexual harassers minimizes the seriousness of their actions and treats them as harmless mischief-makers.

Minors cannot give consent.

According to the Indian law, those under the age of 18 cannot legally give consent to have sex. While this does make consensual sexual relationships between minors murky waters, the use of the term ‘sex’ should not be used to refer to child sexual abuse and child rape.

Call ‘domestic violence’ what it is!

While domestic violence is a widespread issue in India, media reports of it often shy away from using the term ‘domestic violence’. A study by Pandit & Gilbertson found articles that elaborately described the crime, but failed to use the term ‘domestic violence’. Alternatively, they used the more harmless term ‘domestic dispute’. Reports of domestic violence were also found to subtly blame survivors by mentioning details like the survivor not having reported previous violence, or having stayed in the relationship despite previous violence.

By ignoring the generic term ‘domestic violence’, the media shies away from indicating the systemic nature of domestic violence. In their study, Pandit & Gilberston found a surprising absence of media coverage of domestic violence. While most gender-based violence is perpetrated by intimate partners or family members, only 19.2% of English articles reported violence done by a family member. In contrast, NCRB data shows that relative-perpetrated crime is 32.6% of crimes against women in India (which is also a lowball figure, as 99.1% cases of sexual violence in India go unreported).

Also read: Does News Framing Change How We Understand Rape?

The media is urged to treat crimes of sexual violence with the gravity they deserve, without sensationalising or minimising their importance.

About the author(s)

Asmita is a Freelance Communications Consultant, and specialises in leading digital advocacy campaigns for social and gender justice issues. When not using social media for work, she uses social media for fun (and a healthy dash of existential despair).