It was the summer of 2019, and something was not quite right. I was fresh out of an ‘race and gender’ class. I had just slept with an anonymous woman I’d met in a bar, who afterward shared a horrifying tale of systemic abuse that she was going through at the hands of a man, a white man. Anger – fast, pounding rage- rapidly replaced the giddy rush of sex.

My thoughts were too vast for the confines of my mind. As she slept, I began bombarding my graduate school classmates, scattered all across the world, with texts screaming about how unfair the system was, how full of prejudice the world, and how nobody, absolutely nobody cared enough to do anything about it. I sent out one text after another, pouring all my fury into people’s WhatsApp inboxes. “Padmini, you are triggering me,” replied one person. Several others stopped engaging.

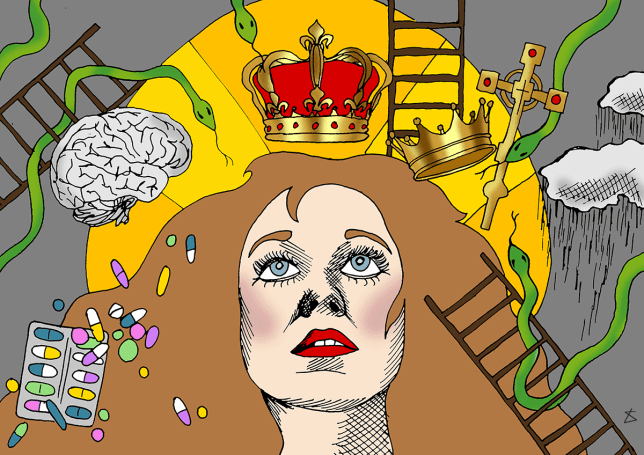

Bipolar disorder is a two-headed hydra; it has a manic side, characterized by increased grandiosity, racing thoughts and activities that can result in painful consequences, and depression, leading to a loss of interest in almost everything combined with intense feelings of worthlessness.

A mug of gin teetered precariously at the edge of the table next to me. With each sip, I grew further emboldened, right up until, 24 hours and about 600 messages later, I decided, calmly, to kill myself. The world was too unfair, I had no one who understood, and everyone was trying to silence me or drown me out. In my mind, I had reached peak intersectional horror – I was being repressed because I was a woman of colour, queer, and outspoken. I would martyr myself to the cause. I passed out blind drunk before I could make an attempt, and after waking up I spent the next twelve hours wandering around the city in a frenzy, getting into lengthy conversations with strangers, calling up professors, and proclaiming that I had found a solution all the critical challenges in my field.

I was going to change the world, really change it. Colours exploded bright in my brain. I felt keenly alive, and invincible. I laughed. I cried. I waltzed on the streets to a chaotic symphony that only I could hear. By the time I was dragged to the hospital, I was babbling rapidly and incoherently, pleading to not be treated by a white doctor. That was my last prayer before the IV pierced my skin, and sedatives flooded my body, granting merciful release to a mind plagued by racing thoughts. I didn’t know it then, but I had just had my first manic episode.

Bipolar disorder is a two-headed hydra; it has a manic side, characterized by increased grandiosity, racing thoughts and activities that can result in painful consequences, and depression, leading to a loss of interest in almost everything combined with intense feelings of worthlessness. Depression is inevitable after a manic breakdown – a month after my episode, I began to feel listless, and found myself unable to focus on things that used to give me immense pleasure. Where I was hypersexual, I found myself unable to even feign interest. I could barely get up from bed, much less focus on research.

Also read: The Ideal Of ‘Recovery’ – What Does Care Look Like?

Worst of all, I found myself unable to care about issues that I would normally have poured my heart and soul into (I was Assamese, after all. Wasn’t I supposed to be agitated by the tragedy that is the NRC?) I dropped out of graduate school for the year. I tried it all – I had a psychiatrist, a therapist, an exercise routine, supportive friends, and hobbies to distract myself. I hadn’t touched a substance in months. Nothing worked. Six months of this hellish existence ensued and I finally decided, calmly, to kill myself. What was the point in living, I reasoned. I had come full circle.

Though data on bipolar disorder is incomplete and far from reflective of the true picture, statistics show that 0.6% of the world currently lives with this condition. Of these, a majority are women. Studies reveal that depressive episodes and suicide attempts occur with greater frequency among women with this condition. Women experience more instances of ‘rapid cycling’, with fast and frequent mood swings.

Though data on bipolar disorder is incomplete and far from reflective of the true picture, statistics show that 0.6% of the world currently lives with this condition. Of these, a majority are women. Studies reveal that depressive episodes and suicide attempts occur with greater frequency among women with this condition. Women experience more instances of ‘rapid cycling’, with fast and frequent mood swings. It has also been found that women report greater impairment in physical health and pain.

While the menstrual cycle is no walk in the park for any woman, for bipolar women the experience is nightmarish, where both anxiety and depression symptoms get elevated. Research also shows that women suffering from this condition are more likely to report a history of sexual abuse – a finding that checks out in my life. Women are often misdiagnosed, receive little psychiatric treatment, and are at extremely high risk for substance abuse and violence.

7.6 million people in India have bipolar disorder. Of this, around 70% do not get treatment of any kind. It would not be an absurd extrapolation to say that given the gendered nature of the society we live in, most women, especially from low-income backgrounds, are likely slipping through the cracks of this disorder. Given that between 25%-60% of people with bipolar disorder will attempt suicide at least once, with a 4-19% success rate, the consequences of leaving bipolar disorder untreated are too horrifying to think of. I acknowledge my privilege in having had access to appropriate healthcare; the outcome would have been fatal otherwise.

Also read: 5 Things Educational Institutions Can Do To Become Mental Health Friendly

My story does not click into place with a happy ending yet – I am still out of school, and still struggle certain days. People don’t always get it, though I am grateful for the few who do. Yet, as Kay James Redfield puts it in her seminal book on bipolar disorder, An Unquiet Mind, we bring to the world a “great deal of energy, fire, enthusiasm and imagination.” Every day, it gets a little easier. And I get a little bit more ready for the day when I can act on the fiery ideals that still guide me.

Assamese and proud, Padmini is a Master’s student at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in Boston. She holds a law degree from the National Law School of India University, Bangalore. She focuses on gender and its intersection with migration, technology and informal finance. She identifies as queer and writes about mental health challenges. You can follow her on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Featured Image source: Metro