The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a new vocabulary of—“health care first” and “physical distancing”—and the most prevalent liberal (read: ignorant) solidarity statement “we are all in this together”. It has also exacerbated the existing socio-economic inequalities leaving a huge chunk of the world population without any real choice of maintaining physical distancing. We are now face to face with the basic survival question which has also made the demands for a universal access to go beyond “roti, kapda aur makaan (food, clothes and housing)” and include health care (including menstrual health care) etc.

This dilemma became almost palpable when in mid-July this year, the state authorities in Bangladesh arrested the owner of a hospital in the capital city Dhaka, busting an undercover market that had “sold migrant workers thousands of certificates showing a negative result on coronavirus tests, when in fact many tests were never performed,” for 59$ apiece.

These migrant workers are mainly the ones who work in unorganised sectors mostly in Europe in grocery stores, restaurants and as hawkers sending back home a large portion of their income. The extension in lockdown and fall in the demand side in most of the economies in the early months of the pandemic, have hit the informal sector in the worst possible ways increasing the precariousness in the lives and livelihoods of the migrant workers; several industries have been entirely disrupted and millions have lost their jobs globally.

Economic analyst M.K Venu calls the ‘remittance economy’ (which has been an important source of boost in the consumption levels in the home country of a migrant worker), a “welfare cushion” for the middle- and lower-income level countries which means that with loss of jobs and uncertainty about the return of migrant workers to Europe or Gulf countries, the number of families of workers below the poverty line in South Asian countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal and India will show a considerable increase.

The market for fake COVID-19 negative reports in India is also on a surge as the unlocking of several economic sectors have started since the last month. Almost all the employers are mandatorily demanding COVID-19 negative reports before offering employment and it is also required by several state authorities as relaxation is given for inter-state movements.

India and Fake COVID Negative Certificates

The market for fake COVID-19 negative reports in India is also on a surge as the unlocking of several economic sectors have started since the last month. Almost all the employers are mandatorily demanding COVID-19 negative reports before offering employment and it is also required by several state authorities as relaxation is given for inter-state movements.

The non-existent employment opportunities in small towns and rural India and low wages paid in Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) (that is, if a worker is somehow able to secure work under it) and the failure of the beneficiary schemes made by the government under the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self Reliant India Campaign) in the wake of the migrant crisis, has been a driving force in the return of these workers to the cities.

Earlier this month Ludhiana police nabbed a quack who was selling fake COVID-19 negative certificates to migrant workers in the state, who wanted to travel to other states to join the labour workforce.

In the beginning of July this year, an expose video went viral in which an official from a private hospital in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh can be seen giving assurances about arranging fake COVID-19 negative report for a patient. Police has registered a case against the man in question and cancelled the hospital’s license. It’s a very tricky space to take legal actions because closing an entire hospital means limiting the access of people to healthcare which can lead to serious consequences in the locality, but not taking any action leaves open the possibility for another racket of fake COVID-19 negative reports which might endanger many more lives.

Also read: COVID-19 In India: The Shunned & The Forgotten Migrant Workers

“Coronavirus better than hunger”

“I am scared but I am also scared to live here. How will I eat and feed my family?” said Mr. Prasad who worked as a technician in a firm in Kolkata but has been living unemployed in Uttar Pradesh for months.

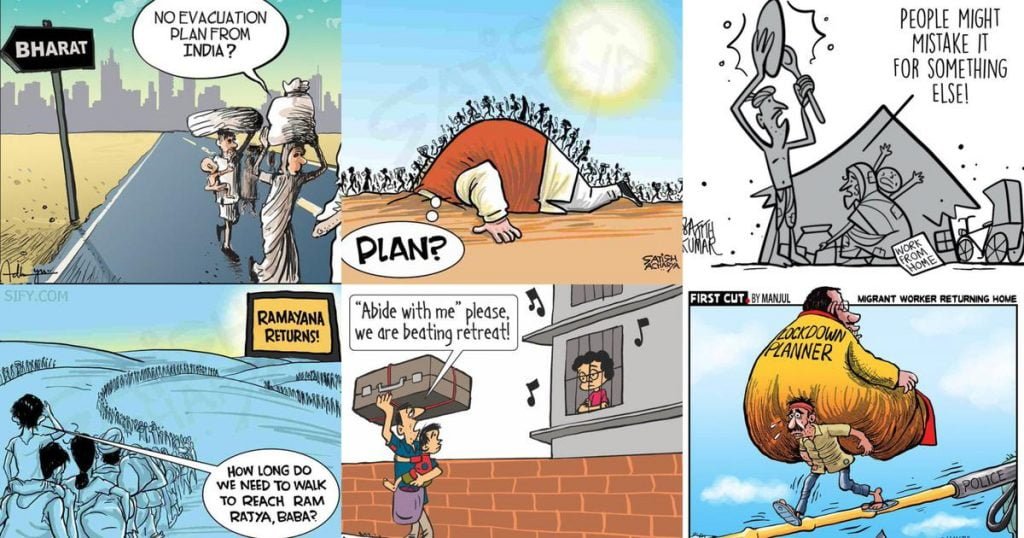

When the nationwide lockdown was announced in the month of March this year, without any prior notice on the pretext of corona virus, India along with the pandemic witnessed a migrant crisis. It did not shock those who were aware of the life realities of migrant workers and the industries that survived only by violation of labour laws, but for the major chunk of the population this was an introduction to the looming crisis that started developing after the Indian economy opened up in the 1990s that intensified urbanisation and informalisation of most of the sectors and the state conveniently distancing itself from the obligations of a “welfare state”

The lockdown meant that all the industries and other activities like construction work etc. was put on a halt leaving millions of migrant workers jobless and stuck in places like Delhi, Mumbai, Tamil Nadu etc., as the transportation facilities also became scarce. Most of these migrant workers returned back to their villages in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Assam, to name a few by covering hundreds of kilometres on foot and hitch-hiking wherever possible. These workers who had formed the underbelly of most of the metropolitan cities talked about the abandonment that they faced at the hands of the “city-dwellers” and pushed the question of belongingness in urban spaces of the country.

Now with the economic activities slowly opening up post-lockdown, workers who have been living in their native villages for months, unemployed and uncared for by the government and with their meagre savings finished are on a run again to find work.

The Disproportionate Impact on Womxn Migrant Workers

Womxn seem to be missing entirely from the mainstream coverage of the migrant crisis as if they were not right there working and then walking for miles, carrying their toddlers, giving births and also facing death as the pandemic deprived them of social security and work.

Humanitarian crisis or any crisis for that matter weighs disproportionately when faced by womxn given the existing patriarchal gender relations which favour men both in the ‘reproductive’ and ‘productive’ spaces. The informal sector of the country employs almost 94% of the womxn where huge inequalities exist in the form of pay gap etc. In urban cities, womxn migrant workers work mostly as domestic helps, care workers or in casual work such as construction sites with no regular pay or social contract, all of which are worst hit by this pandemic.

Womxn migrant workers while returning back to their ‘homes’ had to use ashes and cloth during their menstruation with no access to sanitary pads or other safe alternatives as menstrual health management (MHM) failed to become a priority for the government; which also became evident when the government chose to exclude sanitary pads from the list of essential goods initially after the lockdown which affected the production and supply of sanitary pads in the interior parts of the country.

A recent report contends that the pandemic is most likely to damage the little progress that India made with respect to the maternal mortality in last two decades and with expensive and more COVID-19 focused hospitals, migrant womxn face serious threats.

The risk becomes extreme in the case of pregnant womxn workers who walked for days with insufficient access to nutritious food, water, medical assistance or even rest. A recent report contends that the pandemic is most likely to damage the little progress that India made with respect to the maternal mortality in last two decades and with expensive and more COVID-19 focused hospitals, migrant women face serious threats.

The female labour force participation (FLFP) rate in India has been on a decline during the last few years and the pandemic might intensify this trend. Even with economy opening with high unemployment rates, womxn migrant workers will have it worse as they search for work in a market that favours a male laboring body over other bodies.

Also read: Migrant Women Workers on the Road: Largely Invisible and Already Forgotten

What’s the Way Forward?

The internal migrant crisis in India demands a structural change, essential for ensuring the social, political and economic rights of the migrant workers who form the backbone of Indian society as well as the economy.

The Working Group on Migration formed by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, the first ever task force on migration, set up in end-2015 gave several recommendations for ensuring the constitutional rights of the migrant workers. It suggested in the favour of creating measures of social security, easy self-registration process, a way to ensure the access to Public Distribution System (PDS) for food grains something to which the migrant workers lose access when they move to another state, childcare and effective education for the children of the workers, healthcare among other things.

In this light, it is also important for the policy makers to stretch their imagination in order to deal with the migrant workers issues as well when they set out to design development models for cities because the magnitude of this crisis calls for national level policy intervention and apparently no reactionary plans for their betterment is going to work in the long run.

Featured Image Source: The Quint

About the author(s)

Aparna is a post-grad student of Women's Studies at TISS, Hyderabad. When she is not talking about intersectional politics and re-reading The God of Small Things, she can be found listening to Mehdi Hassan while she pets cats and collects yellow flowers.