I recall a conversation on a summer evening during my third year at Lady Shri Ram college with the gentleman driving me back to the LSR hostel in an autorickshaw. He asked about what I study and how much the tuition and accommodation fees were, saying that his daughter might love to attend the college once her schooling was complete. I tried to give him as much information as possible, though it was clear from his reaction that the amount was too steep. I urged him to tell his daughter to study hard so that she could clear the cutoff and avail of scholarships as LSR was a fantastic college to attend and it would change her life. I was 20, idealistic and ignorant.

Over the next few years, I learnt that the educational institutions that did change my life were and continue to be extremely dangerous spaces for everyone outside my circle of privilege. Several detailed writings, acts of protests and activism from my peers, juniors and seniors belonging to minority groups – DBA, Muslim and queer students as well as alumna – have contributed to busting the myths surrounding the ‘magic’ of institutions like LSR which operate with and enforce narrow self-serving definitions of empowerment. And yet, these institutions refuse to learn and take responsibility for the suffocating atmospheres of discrimination, humiliation and insensitivity that they continue to perpetuate.

Also read: How LSR and Other Women’s Colleges Limit Their Students

In the days following 3 November, 2020 , I was informed, like many of my peers, by news articles and social media posts about the death by suicide of a young woman, Aishwarya Reddy, studying at our alma mater, Lady Shri Ram (LSR) college, University of Delhi.

At a time when low-income students have already been hit hard by government delays in disbursement of scholarships and restrictions over access to resources due to an ongoing, poorly handled pandemic, this news brought a wave of anger over how every elite, apathetic, merit-oriented, highly exclusionary institution that I have been part of or wanted to attend has systematically driven young lives, including friends and acquaintances, to depression and suicide long before we had the pandemic to blame for our structurally violent societies. Having experienced firsthand how the financial and emotional cost of education can drive someone to suicidal thoughts, I feel all the more compelled to stand against institutions such as LSR avoiding accountability for their apathy.

According to data from the National Crime Records Bureau, every hour, a student dies by suicide in India, with numbers rising every year. More disconcerting is the apathy of the rushed, face-saving responses from schools, colleges and universities that refuse to accept responsibility or actively create more inclusive spaces that would look after vulnerable students in consultation with them. In the wake of such institutional apathy, it is important to speak truth to power and remind bastions of privilege such as LSR that they cannot, under any circumstance blame a distressed, underprivileged student who was driven to suicide, for their own utter negligence and failure to provide her access to the education she was entitled to.

It is important to speak truth to power and remind bastions of privilege such as LSR that they cannot, under any circumstance blame a distressed, underprivileged student who was driven to suicide, for their own utter negligence and failure to provide her access to the education she was entitled to.

The declarations from one of LSR’s alumni associations, ELSA, as well as the college’s principal Suman Sharma, as reported by several news portals, are a deplorable and shameless attempt to shift responsibility to the victim, to say the least. More worrisome is that they carry extremely damaging statements blaming the deceased student for not having reached out to the department or LSR‘s administration regarding her troubles.

The reactions which have been very rightly condemned by several student groups and alumni as callous acts of victim-blaming, also reveal a dangerous lack of understanding on the part of those running our educational institutions, around both student welfare and mental health. There are several reasons why such statements need to be panned in the strongest terms. They are more than just insensitive. They perpetuate a violent culture by which privileged classes and authority figures continue to invisibilise and silence the struggles of all those oppressed by their exclusionary systems.

First of all, saying that the student never communicated her difficulties is categorically false. In a survey conducted by the LSR Students’ Union, and carried by several news articles now, the student had clearly identified problems in attending online classes owing to lack of a laptop or a reliable internet connection. The same survey found that at least 30% of students did not have access to laptops or stable internet. In a recent article published by Huffpost India, the LSR student union members mention that they submitted the survey results to the principal and the administration despite which no action was taken to ease the burden on students.

Moreover, the recent LSR regulation to deprive students of the hostel after the first year placed the deceased student’s family (already under severe financial strain) in a precarious position during economic recession. Why was there no safety net for a low-income student who had to forfeit a hostel spot in the middle of a pandemic when her government scholarship had not yet reached her?

Secondly, even if a student does not reach out in person, is it not the responsibility of the college authorities to reach out and follow through on the situation of each student losing accomodation and arrange to make exceptions for those who cannot afford to leave? Was it not the responsibility of each department to follow through on their students’ capabilities to attend classes online and pool resources to support those who need it most? LSR has an office designated for student welfare. What was that office doing when the welfare and indeed the life of a student was at stake?

Finally, the principal’s stance sends out a clear message that the onus is completely on students to come forward with the issues that studying in an elite, aloof institution places upon them. Requiring a disadvantaged student to reach out to authorities by themselves is insensitive and places the student in an extremely vulnerable position.

There are many reasons why students who feel alienated by their circumstances or social location may not want to reach out. First off, universities have a disgraceful track record with regards to providing support to students with grievances of any kind. We cannot forget how not so long ago in 2017, a crowdsourced list of sexual predators in academia was at the forefront of India’s #MeToo movement, and crushed the illusion that “due process” had ensured safe college campuses.

Immediately after the list came out, prominent upper-caste female professors, so-called icons of Indian feminism, rushed to ‘stand by’ their male colleagues who had been named and shamed in the anonymous list, just like ELSA has rushed shamelessly to stand by LSR at a moment’s notice instead of with the late student and her family. Regular channels of seeking assistance in elite Indian colleges have proven to be largely ineffectual or counter productive since most of these institutions are still classist, casteist, racist and homophobic spaces lacking diversity and sensitisation in their management, staff and curriculum.

As a result, the fear of coming forward with a problem that differentiates one from their peers can be very strong. The chances of being ignored, shamed, rejected, gaslit, outed, threatened and ostracised are extremely high.

Second, the stigma surrounding mental health in India creates an added layer of alienation that prevents safe conversations with peers or teachers and often even close friends or loved ones. Mental stress on students has no doubt intensified due to the pandemic and is exacerbated by the tendency of colleges and universities to take snap decisions crucial to students’ futures without consulting the students in question.

Many of these decisions do not affect financially well-off, largely upper-caste students whose families are able to bear the overhead costs such as arranging private accommodation, or hiring private therapists to care for their child’s mental health. As a result, disadvantaged students often find themselves alone in their fight to claim their rights. Colleges and universities such as LSR need to stop acting as if suicides are isolated cases of severe mental illness beyond their purview.

The statements from LSR’s ELSA and Suman Sharma shockingly blame the student for not availing counseling services provided by the college. This automatically assumes that said counseling provided is adequate or effective. Moreover, blaming the student for not seeking mental healthcare when what she needed was immediate financial help for the acute poverty which LSR’s arbitrary rules placed her and her family in, is like handing out a band-aid for a gunshot wound.

Finally, such reckless statements made by authority figures regarding cases of suicide further prevent students from bringing up their problems. The college principal, Suman Sharma has stated to reporters how the non-disbursement of government scholarship funds to the deceased student is not her responsibility. One may argue that universities in India are strapped for cash with the central government continuing to spend as little as it possibly can on education, and may not be able to step in when government scholarships are delayed or denied. And while government apathy is another very real issue that must be spoken out against, neither that nor the pandemic can be used as an excuse by LSR to not do anything that could have helped a bright student who was extremely keen on continuing her education.

In order to act with empathy and provide the expected support, universities require a sensitised staff and administration that care first and foremost about the well-being of students, instead of creating cold, contractual spaces treating education as a transaction. Why did LSR administration never respond to data about student distress? Why do they have to be reminded in the first place to carry out the basic responsibility of checking in on students during a pandemic? Could the college not have spoken to its student body and provided some form of concrete reassurance to those disadvantaged by the new rules instead of expecting them to expose their vulnerabilities in such uncertain times? Could ELSA not have created the charity they are publicising now when the lockdown was announced or when the hostel rules were revised? Could the authorities not have informed her of alternative sources of funding while she was waiting on her scholarship? Or at the very least temporarily helped her with equipment and internet?

Also read: Will Indian Campuses Ever Acknowledge The Mental Health Issues Of Its Students

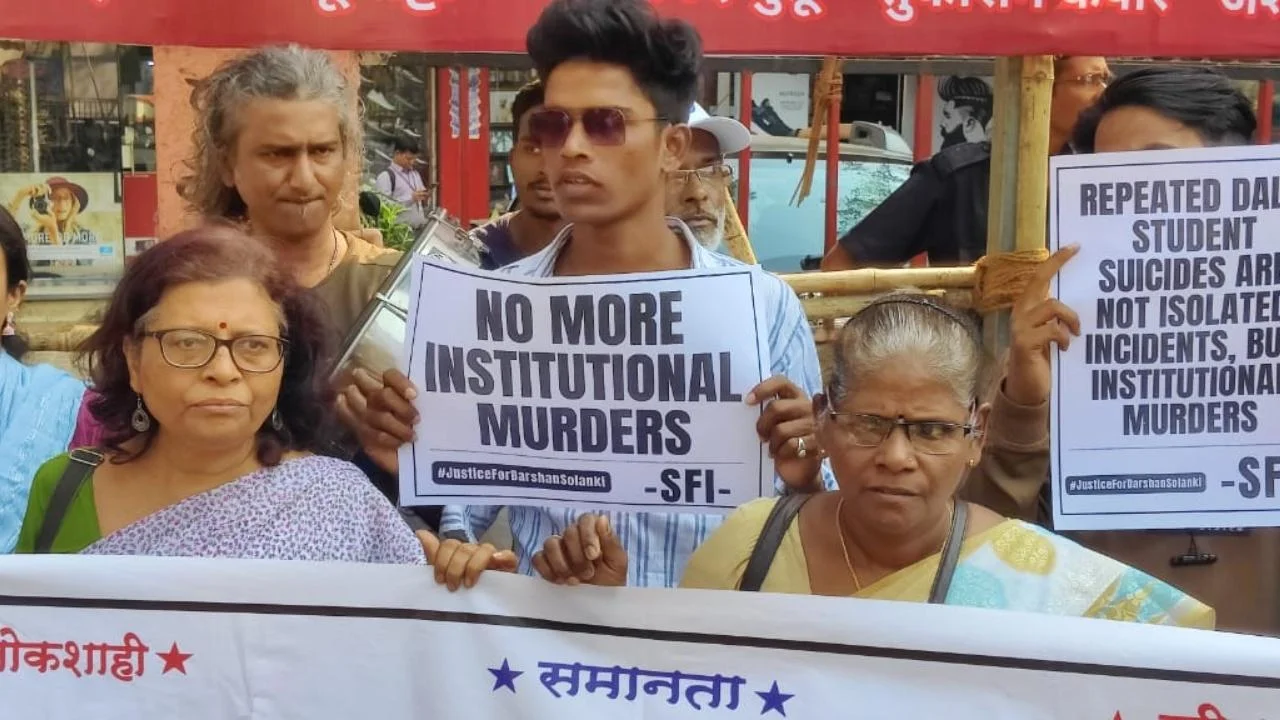

We as alumna of LSR must keep on asking these questions of the college authorities, and of every institution that perpetuates such a culture of exclusion. We must hold the college accountable for its negligence and brazen attempt to shift responsibility for the death of a young student. The principal of LSR must resign. This is not an unfortunate incident. This is institutional murder.

We as alumna of LSR must keep on asking these questions of the college authorities, and of every institution that perpetuates such a culture of exclusion. We must hold the college accountable for its negligence and brazen attempt to shift responsibility for the death of a young student. The principal of LSR must resign. This is not an unfortunate incident. This is institutional murder.

Saranya Nayak is a filmmaker and sound designer from Kolkata, currently pursuing an MFA at USC School of Cinematic Arts. As part of her Visual Anthropology studies, her fieldwork has largely been focused on documenting night worlds and non-spaces. She is working on developing long-term multimedia projects that will support research-backed stories driven by underrepresented voices in Indian film and media. She can be found on Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

What is the role of student groups? Just blaming the govt and institution? Then why do they exist in the first place?

It is extremely sad that so many intelligent minds are buried. Future scientists will be dropping some body in a cab, fine entrepreneur will be washing utensils or doing odd jobs for survival. So many children are unable to pay their school fees are blocked or removed from online classes. That is the very reason my sister started with a group called “Messiah” collecting money from near and dear ones not in cores or Lacs but few hundreds and thousands so that they can pay the school fees for those children whose parents are unable to afford it.